November 1990, U.K.

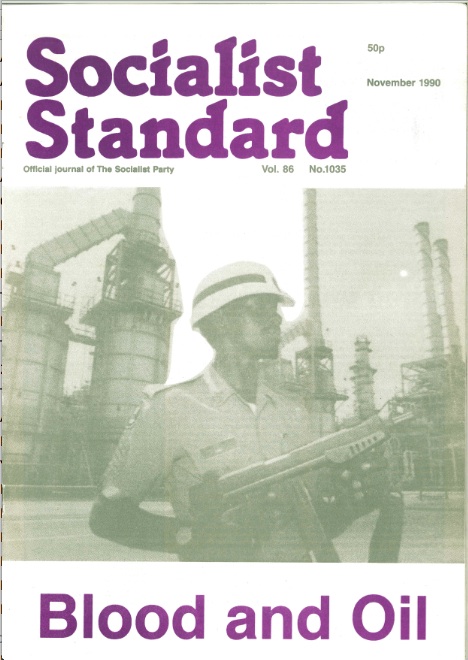

The Prussian militarist Clausewitz declared that war was “nothing but the continuation of politics by other means” . He would have been nearer the truth if he had said that war was the continuation of economics by other means. Since the onset of capitalism five hundred years ago wars have been caused by conflicts of economic interest over sources of raw materials, trade routes, markets, investment outlets and strategic points and places to secure and protect these. The threatening war in the Middle East is no exception to this rule, and in fact strikingly confirms the socialist analysis of the cause of war.

Although it is rather obvious that what is at stake is oil, both sides try to play this down. U.S. President George Bush and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher say that Saddam Hussein is a dictator whose expansionist ambitions must be checked in the interests of world peace. Saddam Hussein says that he has struck a blow for Arab Nationalism by eliminating a state tailor-made by Western imperialism to suit its interests. Saddam Hussein is a dictator and he has taken over a state created by Western imperialism, but it is not for these reasons that the West is preparing to go to war. The Western powers tolerate dictators when it suits their interests. In fact they tolerated, financed and armed Saddam Hussein himself when they needed someone to prevent Iran under Khomeini coming to dominate the Gulf area and threaten their oil supplies. And they tolerated the Indonesian invasion and annexation of East Timor in 1975 as they had that of Goa by India in 1961 without shrieking that world peace and order were threatened. The difference was that, while in East Timor and Goa only carrots grew, Kuwait is situated right in the middle of the world’s largest and lowest-cost oilfields.

Oil and Empire

British imperialism made Kuwait, which remained nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, a “protectorate” in 1899. This was done not for its oil resources, which nobody even suspected existed, but for its strategic position.

At the time Imperial Germany, already squaring up to Britain in the inter-imperialist rivalry which eventually broke out as the First World War, was planning to build a railway that would extend from Europe through Turkey and Mesopotamia down to the Persian Gulf. This was the Berlin to Baghdad railway of history book fame and, if completed, would have represented an alternative and rival to the British-controlled Suez Canal as a trade route to and from the Indian Ocean and the Far East. Kuwait, a small port and pearl-fishing centre at the northern end of the Gulf ruled by a sheik called Al-Sabah, was the likely terminus for the German project. So it was “protected” by British imperialism, to thwart German imperialism.

Oil, however, was soon discovered near Kuwait, first in Persia and then in Mesopotamia. Britain acquired complete control of the Persian oilfields but those of Mesopotamia had to be shared with Germany. As Turkey had entered the First World War on the side of German imperialism, the British and French imperialists made plans to carve up the Ottoman Empire amongst themselves in the event of victory. A secret agreement in 1916 gave what is now Syria, Lebanon and the northern part of Iraq to France, and Palestine and what is now Jordan and the southern part of Iraq to Britain.

Almost as soon as the agreement had been signed, someone in the British Foreign Office realised that a ghastly mistake had been made: northern Mesopotamia contained the oilfields of Mosul and Kirkuk. The French were persuaded on some pretext to agree to a rectification, and after the war the spoils were divided along the lines of today’s Middle Eastern states. Iran is just as much an artificial creation of Western imperialism as Kuwait, though its ruling class ought to be grateful that perfide Albion outwitted French imperialism, otherwise its northern oilfields would be in Syria.

Britain creates Kuwait

Kuwait remained a British protectorate when Iraq became an independent state in 1932, but the new Iraqi rulers were not happy about being deprived of a secure outlet to the Persian Gulf. A glance at a map of Iraq will show that it only has two possible outlets to the sea. The first is via the Shatt al Arab river, but this is shared with Iran. The second is via an inlet to the west, access to which is controlled by two islands belonging to Kuwait.

At one time—in the fifties when Iraq under a pro-Western king and government seemed firmly anchored in the Western camp through its membership of CENTO, the Middle Eastern equivalent of NATO—British officials considered making some concessions to Iraq on this issue, but this was blocked by the Al-Sabah dynasty. The Emir of Kuwait, which since 1946 had become an oil-producing area with huge reserves, proved to be the better judge of his interests. On 14 July 1958¸ the king of Iraq and his pro-western prime minister were overthrown and killed in a military coup led by pro-Nasser army officers. The British Foreign Minister, Selwyn Lloyd, rushed to Washington to discuss the crisis. On 19 July he sent a secret telegram, recently released under the thirty-year rule, to Macmillan, the Prime Minister, in which he reported:

I am sure that you are considering anxiously the problem of Kuwait. One of the most reassuring features of my talks here has been the complete United States solidarity with us over the Gulf. They are assuming that we will take firm action to maintain our position in Kuwait. They themselves are disposed to act with similar resolution in relation to the Aramco oilfields in the area of Dhahran, although the logistics are not worked out. They assume that we will also hold Bahrain and Qatar, come what may. They agree that at all costs these oilfields must be kept in Western hands. The immediate problem is whether it is good tactics to occupy Kuwait against the wishes of the ruling family.

Selwyn Lloyd went on to discuss the options, including turning Kuwait from a protectorate into a colony, i.e., annexing it as Iraq has just done, but rejected this in favour of another option:

On balance, I feel it very much to our advantage to have a kind of Kuwaiti Switzerland where the British do not exercise physical control. (Independent, 13 September).

This was the solution eventually adopted and in 1961 Kuwait was granted “independence” in the sense of no longer being subject to direct “physical control” by Britain. Iraq immediately moved its troops up to the border—and British troops had to be rushed in to prop up the artificial Middle Eastern “Switzerland” that their government had just set up.

Kuwait survived and its rulers prospered. Thanks to revenues from oil, the ruling Al-Sabah dynasty became one of the richest families in the world, overtaken only by fellow oil nouveaux riches the Saudi royals and the Sultan of Brunei, and far surpassing other dynastic billionaires like the Queen of England and Juliana of the Netherlands.

The Shatt al Arab War

Iraq meanwhile also developed its oil resources and revenues, which were mainly used to build up its armed forces so strengthening the grip of the military on the state. Iraqi politics came to consist of coups and plots and counter-plots amongst the leaders of the armed forces. Out of these Saddam Hussein emerged as top dog in 1979.

The current Iraqi regime, though in fact a military dictatorship pursuing the national interests of Iraqi capitalism, has as its ideology the Pan-Arab Nationalism of the Baath party. Iraq, however, is by no means purely an Arab country since up to a quarter of its population speak Kurdish rather than Arabic, and the attempt to impose Baathism in the 1970s led to a revival of the armed revolt of Kurdish nationalists in the North of the country, where the oilfields of Mosul and Kirkuk are situated—which explains why Iraq has been prepared to use all means, including, more recently, poison gas, to retain the area.

This revolt was encouraged as a means of weakening Iraq by the Shah of Iran, whose country had a long-standing dispute with Iraq over the control of the Shatt al Arab river. The dispute went back to the time of the first commercial exploitation of Iranian oil before the First World War and concerned Iran’s demand for access and protection for its bordering oil wells and installations.

The Shatt al Arab is the name of the river formed by the confluence of the Euphrates and the Tigris. From the Iranian town of Khorramshahr to the sea it forms the frontier between Iraq and Iran. Safe, free navigation in this waterway is absolutely vital to Iraq as its main port, Basra, can only be reached via the Shatt al Arab. Without this, Iraq becomes virtually a land-locked country, dependent on other countries for the transit of its imports and the export of its main product, oil. Its vulnerability in this respect was well illustrated by the ease and speed with which the pipelines via Turkey and Saudi Arabia were closed to enforce United Nations sanctions (and by the fact that a third pipeline via Syria had long been closed by the Syrian government for political reasons).

The Shah’s strategy worked and in 1975 a treaty was signed between Iraq and Iran under which Iraq ceded control of the eastern side of the Shatt al Arab to Iran in return for Iran withdrawing its support for the Kurdish nationalists. When, however, the Shah was overthrown in 1979 and Iran began to slip into chaos, the tables were turned. The Iraqi ruling class decided to use the occasion to attack Iran and regain control of the whole of the Shatt al Arab and perhaps more. So began, in 1980, one of the longest and bloodiest wars of modern history. The war lasted eight years and led to the death of about one million people—all for control of a strategic commercial waterway.

The Western powers were happy to let the war go on, using Iraq to block any Iranian take-over of the Gulf region. When, however, Iran began to attack shipping in the Gulf in 1987, the West was forced to send its own taskforce of warships and warplanes to the area to protect the free flow of its oil supplies.

Why Iraq invaded Kuwait

The war ended in a stalemate, with Iraq in control of some Iranian territory but with the port of Basra blocked. This put pressure on Iraq to turn to its other possible outlet to the sea: that blocked by Kuwaiti control of the islands of Warba and Bubiyan.

The Iraq-Iran war strikingly confirmed a point made in 1938 by the Iraqi Foreign Minister in discussions with his British counterpart:

Iraq would like to rent a piece of land from Kuwait for establishing a deep harbour and connecting it to the Basra railway line, since Iraq could not guarantee navigational safety on the Shatt al-Arab in the case of an Iraq-Iran dispute. (Quoted in press release on “The Political Background to the Current Events” issued by the Iraqi Press Office, London, on 12 September, pp 16-17).

The present Iraqi Foreign Minister, Tariq Aziz, has made it quite clear that Iraq’s motives for taking over Kuwait were economic, commercial and strategic. In a letter on The Kuwait Question sent to all foreign ministers on 4 September he denounced Britain for having created and sustained since 1899 an “artificial entity called Kuwait” which cut off Iraq from “its natural access to the waters of the Arab Gulf”, and went on to say that all Iraqi governments since the establishment of the state of Iraq in 1924 had insisted that Iraq must have Kuwait to guarantee its commercial and economic interests and provide it with the requirements necessary for the defence of its national security.

King Hussein of Jordan brought out the same point, in a message broadcast on the American TV network CNN on 22 September 1990, when he said that Iraq had been seeking:

an agreement with Kuwait that would secure it an independent access to the sea which it considers of vital national interest.

The phrase “vital national interest”, invoked by both sides in the threatening war, is the key as in the mealy-mouthed language of diplomacy this refers to issues over which states are prepared to go to war in the last resort.

Iraq emerged from its war with Iran with a huge financial debt and a desperate need for money to pay for reconstruction. With oil revenues as virtually its only source of income, Iraq favoured using the OPEC cartel to push up the price of oil by restricting its supply. Since this was in the interests of a number of other OPEC members, including Iran, some move in this direction was agreed. However, two countries in particular—Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates—failed to apply this. They consistently exceeded their quotas, so preventing the price of oil from rising.

The reason why the emirs and sheiks and sultans of the Gulf pursued this policy was not shortsightedness or cussedness. It was because it had become in their economic interest to do so. The Al-Sabah family had not wasted all its riches on horse-racing, gambling and gold-fitted bathrooms. Most of it had been re-invested in capitalist industry and finance in the West, so much so in fact that a large part of Kuwait’s income came from these investments. In other words, the Kuwaiti and other Gulf rulers had become Western capitalists themselves and not just oil rentiers—with the same interest in not having too high a price for oil.

Iraq regarded this refusal to take steps to raise the price of oil as a plot to prevent it recovering from the war. Combined with their long-standing claim to Kuwait as a means of obtaining a vitally-needed secure trade route to the sea, this decided the Iraqi ruling class to take military action. On the night of 1/2 August 1990 Kuwait was invaded and later annexed. As an additional bonus, the Kuwaiti oilfields when added to the Iraqi ones make Iraq potentially almost as big a producer sitting on as big reserves as Saudi Arabia.

Why the West is going to war

Bush, and Thatcher who happened to be in America on a lecture tour, reacted quickly, issuing an ultimatum to Iraq not to move further down the coast and take over the Saudi oilfields and dispatching a battle fleet to the Gulf for the second time in three years.

Iraq probably had no intention of invading Saudi Arabia, but America had every interest in finding an excuse to send troops to protect the Saudi oilfields. Since 1950 these had been an American preserve: under an agreement with the King of Saudi Arabia European oil companies were excluded and US ones, grouped together as A.R.A.M.C.O., given a monopoly. In preparing for war by dispatching troops to the Gulf, Bush is applying the policy enunciated by Carter in his January 23 1980 State of the Union message:

Let our position be absolutely clear: An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States. It will be repelled by use of any means necessary, including military force.

The Gulf, he explained, was of “great strategic importance” because “it contains more than two-thirds of the world’s exportable oil” and because the Strait of Hormuz at its mouth is “a waterway through which much of the free world’s oil must flow”. At the time the immediate threat was seen as coming from Russia which had just invaded Afghanistan, but the Carter Doctrine applied equally to threats to American oil supplies from other states like Iran and now Iraq.

In Britain the Sunday Times(12 August 1990), which has called for war since day one of the crisis, has been equally frank:

The reason why we will shortly have to go to war with Iraq is not to free Kuwait, though that is to be desired, or to defend Saudi Arabia, though that is important. It is because President Saddam is a menace to vital Western interests in the Gulf, above all the free flow of oil at market prices, which is essential to the West’s prosperity.

If war breaks out in the Middle East, the issues at stake will be purely economic and commercial: access to the sea and a high price of oil, on the one side, and control of oilfields and a low price of oil, on the other. Neither of which are issues justifying the shedding of a single drop of working class blood.

Back to the History Index

Back to the World Socialist Movement home page