A Short Story from the December 1954 issue of the Socialist Standard

Scrooge buttoned his overcoat and picked up his Chronicle, said goodnight to the office and left. This was not the Ebenezer Scrooge who said “ Humbug ” and disliked Christmas but later had a change of heart and died in the workhouse through giving all his money away: this was Stan Scrooge, who travelled on the Northern Line.

He walked home briskly from the station, pleasurably noting seasonable signs everywhere; the inviting tins of pudding and turkey in the grocers’ and the sprigs of mistletoe round the price-tickets, dear old Santa Claus in the Coop doorway, Frankie Laine singing “Silent Night ” in the radio shop in the next street. There was a fresh, crisp layer of snow, and at the corner by the loan-office it was patterned with innumerable converging footprints, as though a pageant of sainted Wenceslases had passed, full of optimism and inspiration. For it was Christmas Eve, the time when men the whole world over feel the warmth of peace and goodwill towards one another. Scrooge passed a paper-boy. The lad, with his glowing cheeks and bright eyes, was the incarnation of the Christmas spirit; his voice fairly rang with it as he shouted, “Thirty more terrorists killed! Read all about it!”

Yes, it was a season of enchantment, Scrooge thought as he let himself into his lodgings. Three Christmas cards, and toad-in-the-hole for dinner; then he put on his slippers and sat by the fire to read his paper. The fire made him drowsy. He leaned back in his chair and folded his hands. In a few moments he was asleep.

When he awoke, the fire had burned down. Scrooge looked at his watch; it had stopped. At that very moment, the clock in the hall began to strike. He counted the chimes—twelve o’clock! Fancy sleeping all that time! Scrooge would have leaped from his chair in dismay, but another sound caught his attention. It was the sound of clanking chains.

Scrooge did not immediately think of ghosts. He had read books published by the Rationalist Press, and therefore despised superstition. In fact, he wondered why his landlady was up so late, and what she was doing. His emotions asserted themselves, however, when the noise ascended the stairs and entered his room. The chains were attached to a shrouded figure which pointed at Scrooge. He suddenly remembered something.

“This happened to someone in my family,” he said. “ Heard my grandfather talk about it. You’re the Ghost of Christmas Past.”

The ghost inclined ils head.

Scrooge sniffed. “Well, I’m nothing like him, you know. Not much to unearth from my past. A girl or two and that’s all.”

As far he could judge, the ghost shrugged its shoulders before it beckoned him to the window. To Scrooge’s surprise, the window was open; to his greater surprise, the two of them floated out. Astonishment over, it seemed a quite natural way of travelling—certainly a satisfactory one, because in seconds they descended several miles away, at a place Scrooge recognized immediately. The biggest football ground in London; broad daylight, 60,000 people, and one team breaking away down the centre. The ghost pointed to a spot in the crowd and drew Scrooge towards it. Half a dozen young men, enjoying one anothers’ company as well as the game.

“Why,” said Scrooge, “ that’s me! And old Johnny Dunn! And—why it’s that match against the Germans: those are the German chaps we got talking to! My word, that’s a few Christmases ago! Before the war, that was.”

The ghost put a finger to its lips. The game was nearly over. They watched the lively conversation, listened to the warm farewells at the end and the two young Englishmen talking as they went off together. They heard Johnny Dunn praise the Germans as decent fellows, and Scrooge saying well, they were human beings just the same, weren’t they? Johnny said that if you thought about it you could see the ordinary people of the world wanted to live in peace. And Scrooge said that was it; the politicians began wars and the common people had to fight them.

It was pretty to hear them. The older Scrooge, slightly puzzled, was led away by the ghost, over rooftops again until they came to a red brick building in a main road. A lot of young men were walking in and out of the building, or talking on the pavement. Among them, Scrooge saw himself.

“I know that,” he said. “ It’s the first Christmas of the war. Just before Christmas, really—when I went to register for the army. And look—that’s just what happened! That fellow talking to me outside the Labour Exchange—I remember him well. Wouldn’t go in the army—just said he wouldn’t kill other working men. Bit queer, he was.”

They drew near. Scrooge saw that he was talking excitedly. “Ordinary people like us? Don’t talk rubbish!” he was saying. “Nothing like us, the Germans aren’t. Arrogant and domineering, that’s their national character. Didn’t you hear on the wireless last night . . .” The other man looked sad rather than angry, and Scrooge felt rather uncomfortable. He felt the ghost was looking at him oddly too, and was glad when they passed on.

A recent Christmas, and Scrooge again condemning a nation—quoting books as well, sitting in his penultimate fiancee’s parlour. This time the Russians, and Joan was full of admiration as he explained about Pan-Slavism, the Russian character, and the menace of Marxism. The spectator Scrooge felt rather proud of himself.

“There,” he said to the ghost, “nothing unreasonable about that, anyway. And you can’t see me fraternizing with any ruddy Russians!”

The ghost took his arm. A few moments, and they were in a theatre. Christmas 1943: Scrooge, on leave, was in the stalls. A fat comedian in lounge suit and panama was speaking solemnly from the footlights. Our gallant allies; their courage, the bond between our two nations; in their honour, and by special request, he would sing “My Lovely Russian Rose.” Scrooge watched himself applauding enthusiastically. As the scene faded, he turned to the ghost.

“You’re too clever,” he said indignantly. “ I’ve a good mind . . . ”

The ghost held up its hand, and again took him by the sleeve. He did not know the time of the scene he was now shown. It was a street of houses, almost totally enclosed from the light, the sky like a strip of faded bunting. The people were ill-clothed and wretched, their children underfed and joyless; dankness and grime so pervaded the whole surrounding as to form a grey texture on the hopeless faces. Scrooge had never known hunger, and he was horrified. He turned to speak to the ghost. It had gone. He turned again, and the narrow street, too, had gone. He was in his own room, standing near his chair. Bewildered, he sat down and, without intending, fell asleep almost at once.

He was awakened again by the clock. As he opened his eyes, he saw that someone was standing there, huge and jolly, holding a flaming torch.

“ Ah! Awake at last!” said the ghost paternally.

“ Christmas present?” asked Scrooge.

“The very same.”

“ More levitation?” said Scrooge.

It shook its head. “A view from the window, that’s all: a mere glimpse of the world around us.”

The window was open again. With the ghost at his elbow, Scrooge looked out. He saw a church hall, drab and bare as those places are. It was snowing slightly, powdering the people who stood in a shuffling, shabby line at the door. Most—not all—of them were elderly. Inside the hall, they advanced one by one to a desk where a man was giving money away. A card said: “ Welfare Officer.”

“What’s this?” said Scrooge.

“ Ah,” murmured the ghost, “you don’t recognize the name. The Welfare Officer—otherwise known as public assistance, the R.O., and even—disrespectfully, of course —the bunhouse.”

“I thought you were showing me Christmas Presents?” said Scrooge.

“Indeed I am.”

“Get away” said Scrooge. “This is what your silent partner was showing me last night. Years ago, this. You don’t hear of people being on the R.O. nowadays.”

“My word,” said the ghost heartily, “ you don’t know much, do you? Thousands of ’em—thousands.” ’“Really?” asked Scrooge. “ But I thought things had improved.”

“You’d be surprised” said the ghost “ A good hundred thousand still call at the R.O. You’d better see this, too.”

It flashed its torch. For a moment Scrooge was dazzled. When he recovered, he saw a bleak, sombre group outside a bleak, sombre building. He asked the ghost if it were a workhouse.

“Dear me, no,’ said the ghost. “ These are free men with money—a little, at any rate—in their pockets.

“ I don’t know it,” said Scrooge.

“ Of course you do,” said the ghost. “ Ever hear of good beds for working men? This place is full of ’em.”

Scrooge stared. “ Do you mean . . . ” he began to ask.

“Sure,” said the ghost. “ And the firm which owns this lot pays very handsome dividends, especially .nowadays. . . . We’ve hardly started yet, though. ’ I’ll show you something else.”

He did. He showed Scrooge poverty he never knew to exist, housing he never knew to stand. Sordidness, wretchedness, degradation—Christmas Present could show them all. Scrooge felt in turn horror, incredulity and anger. Finally he forgot the ghost’s presence, and was scarcely aware when the window closed and he was led back to his chair. Before he fell asleep, he saw the ghost beaming at him and heard it saying: “If it gets you like that, you ought to find the cause, you know . . .” But Scrooge was too tired to hear. He fell asleep.

He dreamed that he talked with the Ghost of Christmas Present What was the point of this harrowing panorama? Scrooge demanded. Because you’re going to change it, said the ghost. By myself? said Scrooge. You and millions more, replied the ghost. But what causes all this? Scrooge asked. You tell me, said the ghost. A lot of it’s’ human nature, said Scrooge. Human nature changes, the ghost replied. I suppose part of it’s the system, Scrooge said. What do you know about the system? asked the ghost. Not much, said Scrooge; was me and the Germans a part of the system? Your nationalism, yes, said the ghost And the bunhouse, the squalor and the wars; you don’t know it yet, and things won’t change much till you do know it. All right, said Scrooge, maybe you’re right: what can I do about it? You must first understand, said the ghost. Scrooge repeated himself: What can I do? Understand, said the ghost Understand, understand, understand . . .

The clock struck twelve, and Scrooge awoke from his dream. Before him stood the Ghost of Christmas Yet-To-Come. It moved aside, and Scrooge was alarmed. His room had gone, and he, his chair and the ghost seemed suspended above a crowd of people. The ghost’s touch reassured him, and he looked down.

The people looked different, strikingly yet in a way that Scrooge could not identify for a time. His final realization came so suddenly that he burst out: “ Why, don’t they look happy!”

“They do, don’t they?” smiled the ghost.

“ Look as if they’ve all become millionaires,” Scrooge went on.

“ Strangely enough, they have no money,” said the ghost.

“No money?” Scrooge was disbelieving. “Get away—they’re not poor.”

“Indeed they are not. But they have no money.”

“Go on with you,” said Scrooge impatiently.

The ghost pointed, singling out a man. Scrooge watched him. “Why,” he said indignantly, “he’s pinching a pair of shoes. He walked into that shop-place and took them—bold as brass, too!”

“They are his,” said the ghost calmly.

Scrooge sat open-mouthed with bewilderment. The ghost pointed to a place where a few men and women were working. “ Ah,’” said Scrooge, “ that’s good stuff they’re making. Taking their time, though. Which one’s the foreman?”

“Everyone makes good stuff,” said the ghost firmly. “ And there’s no foremen.”

“No foremen? But they’d do what they liked!” cried Scrooge.

“They are doing what they like. They are making good things.”

Incredible, Scrooge thought. He wondered if everyone had sufficient, but the evidence was before him. Nobody was opulent, but everyone was prosperous; nobody superior, but everyone satisfied. He asked question after question of the ghost; the answers were shown, not told him. The language itself had changed through the disuse of innumerable words. Worship, sell, steal, envy, profit—hundreds of words that Scrooge heard every day were archaisms to the people he watched now. Others, like war and business, were preserved only for the convenience of historians and word-spinners, as are chariot-racing and alchemy in Scrooge’s day.

He realized suddenly that the scene began to fade. Clutching the ghost’s sleeve, he begged an answer to only one more question. They began to descend through space, and the uprush of air made speech difficult. Shouting, leaning on the ghost, Scrooge demanded: “What Christmas Present said—something I can do to bring it nearer?”

The ghost’s voice was becoming distant, but still was clear. “Understand—first you must understand,” it said. Scrooge pressed closer. “What can I do—do?” he bawled. The voice floated back, as the floor of Scrooge’s room rushed towards him.

“Understand . . . understand . . . understand!”

Robert Barltrop

Another Christmas Story

TOYS GALORE

A STORY FOR GIRLS AND BOYS

Christmas Eve was only twenty-seven days away. A thousand feet down beneath the ice and rock of northern Greenland Father Christmas was feeling pleased and rather excited. In his workshops the output of toys and sweets was going almost exactly according to plan.

And what a plan! Five years ago he had decided that, old as he was, he must move with the times. And he and his elves had begun to modernise and expand his workshops. It was an immense task and it meant a profound change for all of them. But at last it was finished, and everything was working well. Now the production lines and stores and packing departments spread out under ground for many hundreds of metres, and it was all fully automated and computerised. The elves, who had once been craftsmen in wood and metal and leather and pottery and cloth, now sat at control panels and monitored whole banks of machines and conveyor belts. Now they watched over the manufacture and warehousing of a bewildering range of plastic toys, construction kits, bicycles and tricycles, dolls prams, computer games, model space ships, racing cars, toy kitchens and nurses’ outfits, robots, chemistry sets, prehistoric monsters and a wide variety of sweets and chocolates and biscuits and cakes.

Father Christmas himself dressed in his workaday red smock, sat at his control desk, smoothing his white beard and watching the VDU screens as the reports from every section flashed up in front of him. In his mind he was already composing his press statement. This was what excited him. It was something he had never done before, but he had never had such news to tell as this. Now that the reorganisation was complete and everything was working well, he was going to tell the world that, this year, for the first time, he could give every child in the world what they wanted on Christmas morning.

Suddenly making up his mind, he got up and moved across to his world processor. Tentatively, he began to type out his message, going back to insert words here and there, moving paragraphs about, then wiping out fussy details, trying all the time to keep his news short and simple. He wanted everyone to understand the significance of the change that had taken place – how it would affect them all, but particularly the children.

For as long as he could remember – a great many years – he and his helpers had toiled without rest to make a few hundred thousand presents every year to take to a few hundred thousand children in just a few parts of the world. There was never enough: never enough time; never enough hands to do the work; never enough materials, tools or energy to drive the machinery. And so most children had to go short, and many more had to go without. Now, all that had changed. Father Christmas had at last caught up with the modern world and could now turn out an almost limitless supply of the sort of things that today’s children wanted.

When the press release was finished it ran to just over two hundred words. He read it through again carefully. Nothing boastful or misleading. Just a simple statement of the facts. He hoped that every newspaper and broadcasting station would eventually carry the story in one way or another. He transferred the finished text to the main computer, keyed in Reuter’s code number, waited for the “ready” signal and then touched the “transmit” key.

He made his way to the post room near the surface. The trickle of letters that had started over a month ago had now become a steady stream. By mid-December it would be a flood. Childish handwriting and bad spelling all had to be deciphered and the details entered into the computer where they would form instructions for the packing department. This work could not be automated. It was a job for experts of long experience. Often they had to guess what was wanted or provide substitutes. This year, children who did not write at all were being given standard parcels of sweets and toys. What Father Christmas could not do – and he was acutely conscious of this as he looked at a few of the letters – was to relieve the gruelling poverty of so many of the families to which these children belonged. As he walked along the corridor towards the stables he reflected that perhaps his new initiative might point the way to ending the deprivation of adults too.

The new sleigh was a massive affair. In spite of its traditional appearance, it was really a huge VTOL aircraft more like a spaceship, with vast load carrying capacity- It was their own design, and its test flights had probably given rise to some of the UFO stories that had spread around the world in the last two years. It incorporated one piece of advanced technology that far surpassed anything they had copied from the world outside a transporter which would beam down presents to children while the sleigh flew over at high speed, miles above.

The reindeer knew that their formation ahead of the sleigh was now symbolic rather than functional but still they were getting restless, faintly sensing the seasonal change in the air above, eager to begin their annual

journey. Father Christmas walked slowly from stall to stall, murmuring softy to each one, calming and reassuring them.

When he returned to his control room, over an hour later, his computer screen carried the notice that an incoming message had been received and required an answer. When he called it up on the screen, it read, “Reuterlond to SaCIaus Greenld. Request clarification your 1343.55 hrs 281186. Please confirm extent of enhanced Xmas delivery”. It irritated him. He replied tersely that all children, everywhere would have presents delivered – where available, those they had requested. And then he settled down again to the job that he and the computer had been doing for weeks – the complicated planning of his delivery flights throughout the dark hours of Christmas Eve, right around the world.

He was not left in peace for long. A reporter on a New York newspaper sent a message requesting an interview. He replied immediately that he did not give interviews. In the following two hours more than thirty similar requests came from different parts of the world. He sent the same reply to all of them, adding to the later ones the emphasis that he never had given interviews and never would. But he was worried. This was not the sort of reaction he had expected. There were no congratulations or expressions of pleasure at his news.

He became more worried, even alarmed, when he began to receive offers to appear on television. Now he wished that he had told them nothing. Surely they understood that he never appeared in public did not want any publicity for himself, disliked even being seen. Replies to that effect seemed to do the trick. The screen stayed blank and he was able to get on with his work again.

It lasted three days. Then the real trouble started. The first indication of the way things were going came from a Hong Kong toy company. It complained of what it called “unfair competition”. This was followed by a long series of calls from toymakers’ federations, confectionery groups, chain stores, trades councils and even transport associations, using expressions like, “We hope there is some mistake. . .”, “. . . view with grave concern. . .”, “. . . lack of consultation . . .” First he became agitated and then, increasingly, angry. None of them seemed to have any concern at all for the children they were supposed to be serving.

By the end of the week, even governments’ boards of trade and foreign offices were asking him to “reconsider” or accusing him of “dumping” – a term he did not understand – and demanding that he attend all sorts of meetings to discuss his plans. Through the dry bureaucratic jargon and the impassive green lettering on the computer screen he could feel a growing panic, almost hysteria, in their messages. They’ve gone mad! he said aloud, but he was deeply upset.

All his work to bring pleasure and happiness to the children seemed to have aroused nothing but dismay and hostility. For a few hours he clung to the hope that, even if these trade associations and government departments did not appreciate the breakthrough he had achieved, then ordinary people would. But angry communications from trade unions representing shop and distributive workers, employees in toy and sweet factories, and even Father Christmases in department stores all but squashed that hope.

But the letters from the children did not stop. They wrote to him in ever-increasing numbers as the day drew nearer and the postal services kept delivering them, many more than in previous years, letters from parts of the world that had never heard of him before. They wanted his gifts, whatever their parents said. And he was determined to go on providing what the children wanted, as he had always tried to do. So when the Food and Drugs administration of the USA informed him that accusations had been made about the purity of his candy and the British Office of Trading Standards questioned the safety of his toys, he ignored them. He ignored the threats of sanctions from the secretariat of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and he smiled dismissively when the United Nations General Assembly informed him that “defensive measures” might be taken if he persisted. He was quite intent on going ahead in spite of all of them. He said, Christmas is for the children. They must know that.

The reindeer behaved well on Christmas Eve. In the steady arctic twilight they streamed north ahead of the sleigh, over the Pole and down the international dateline. At the height they were flying, the sun remained low but visible even when they reached the south Pacific. They traversed Tonga and the neighbouring islands, where the dateline bulges east, in a few swift sweeps and then began to cover New Zealand and the sprinkled islands of Melanesia. The parcels of gifts whistled out of the unloading bay and were steadily replaced by a stream from the cargo hold as they passed over villages and cities and ships at sea. As they swept north over Australia, New Guinea and the Philippines, the earth below was dark but as they reached eastern Siberia the winter sun still lit the frozen land with a dull glow.

Before touching China at all, they returned to Greenland to reload and refuel. And so they worked their way gradually westward around the world.

They were flying south over India when they noticed the first bright flares coming up from the Maldives Islands. They looked a little like fireworks, but they came far too high and fast for fireworks and exploded behind them with shocks that they could feel faintly. “Bless my boots!” said Father Christmas. “They’re shooting at us! ‘Defensive measures’!”

It did not happen again until they were over the Ural mountains in Russia but this time the missiles detonated ahead of them and frightened the reindeer. “Peace on earth, good will toward men” he muttered fiercely through his beard. “They are probably singing that just about now.”

The final deliveries were very late. The sun was already rising over the western states of America and Canada. The sleigh, now minus its reindeer, glinted in the sunlight like a star and left vapour trails high in the atmosphere. The children were already waking but the fighter planes had been grounded. There had been no more attacks since Father Christmas had returned to base and sent out his ultimatum. It was very brief. He simply threatened to tell everyone, parents and children, how they could have plenty of everything they wanted, all the year round, all round the world. And that really frightened the governments. They called off their defensive measures and Father Christmas went on with his task in silence. That is why not many people know about it yet.

RON COOK

Socialist Standard December 1986

God rest ye merry socialists, let nothing you dismay

Remember there’s no evidence there was a Christmas day.

When Christ was born just is not known, no matter what they say,

Glad tidings of reason & fact, reason & fact,

Glad tidings of reason & fact.

There was no star of Bethlehem, there was no angel song,

There could have been no wise men, for the journey was too long,

The stories in the Bible are historically wrong,

Glad tidings of reason & fact, reason & fact,

Glad tidings of reason & fact.

Much of our Christmas custom comes from Persia & from Greece,

From solstice celebrations of the ancient Middle East,

Our so-called Christmas holiday is but a pagan feast,

Glad tidings of reason & fact, reason & fact,

Glad tidings of reason & fact.

author unknown

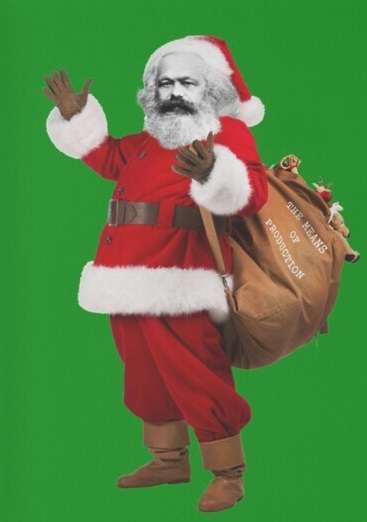

Merry Marxmas from all at WSM