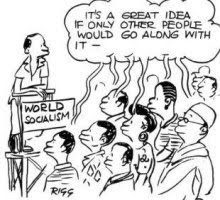

“It’s a nice idea but it will never happen” is one of the most common responses to the suggestion that it is in our interests to work towards building a socialist society. The assumption is that socialism will rely upon everybody being altruistic, sacrificing their own interests for those of others. But socialism would actually involve the majority of people recognising their common interests.

People are too greedy

This is a common objection to socialism, and suggests that, in socialism, some people would take more than their share of goods. Images are conjured up of people walking out of supermarkets carrying stockpiles of food—after all, isn’t that what everyone would do if all goods were freely available?

It may be what people would do in today’s capitalist society, where what we need appears to be scarce because it is rationed by the payment of the wage. But if food were given away free in socialism, there would be no need to take more than you need. Because food will have been produced to satisfy society’s needs, not for profit, it will be available on that basis. The current world food supply (let alone the potential supply) is enough to feed the global population (see How We Could Feed the World)

Besides, we argue that people are not greedy enough! If people were as “greedy” as people claim, why do they give away all their wealth and power to the capitalist class in the first place?

Who would do the dirty work?

This is a common objection to the proposal that all work be contributed on a voluntary basis. Some people point to certain kinds of work that people might seek to avoid—such as cleaning out sewers, or mining. A more extreme form of the argument suggests that everyone would spend the whole day in bed if they were not forced to work.

Humans throughout history have sought fulfillment through their work. If they have not enjoyed their work, it has not been through dislike of work in general but due to the particular purpose and conditions of the work that they have been forced to undertake. Work under socialism has the potential to be entirely different to capitalist employment. The most important reason for this is that unpleasant work could be organised far more efficiently than under capitalism and that all work would be organised so as to be as pleasant as possible.

The purpose of work would be entirely different. Under capitalism, much of the work done is the work required by capitalism in order to perpetuate its own existence. In socialism, the only work that would need to be done would be that for directly meeting human needs. Indeed, interesting and pleasant work is itself a human need. And work that isn’t in itself interesting and pleasant must be minimised or abolished.

If a household gets a washing machine, you never hear the family members who used to do the laundry by hand complain that this “puts them out of work”. But strangely enough, if a similar development occurs on a broader social scale it is seen as a serious problem—”unemployment”—which can only be solved by inventing more jobs for people to do. The fact is that most jobs under capitalism are either completely or partially unnecessary. Many of those that are necessary are performed by stressed people working long hours while others suffer poverty.

In a sane society, the elimination of all these absurd jobs (not only those that produce or market ridiculous and unnecessary commodities, but the far larger number directly or indirectly involved in promoting and protecting the whole capitalist system) would reduce necessary tasks to such a trivial level that they could easily be taken care of voluntarily and cooperatively, eliminating the need for the whole apparatus of economic incentives and state enforcement. That economists now believe that in 20 years time, total world demand for all commodities could be met by 2% of the global population—and this in capitalist society!—suggests necessary work in socialist society could be so organised as to enable individuals to contribute no more than a few hours a week to the good of society.

For more information on this question, see World without accountants.

Are you serious?

Is the revolution we are talking about at all likely? Appearances would suggest not. The odds seem to be stacked against it. Indeed, when we put forward the idea, most people can scarcely believe we are serious.

But most revolutions have been preceded by periods when most people were scoffing at the idea that things could ever change. There was a time when the idea of a capitalist society would have been dismissed as a hopeless utopian dream. To a peasant living in feudal society, the idea of radical change would appear as hopeless as it may appear to you now. To them, feudalism would have appeared as eternal and unchanging and unchangeable as capitalism appears to us now. In Europe, when capitalism was relatively young, the idea of workers working an eight hour day with a weekend would have appeared hopelessly utopian. In the past in countries where everybody now has a vote, there was a time when the idea was scorned and violently opposed.

So we’re not too surprised that people find it difficult to take our ideas on board. We found it difficult ourselves, of course. Yet, despite the many discouraging trends in the world, there are some encouraging signs, not least of which is the widespread disillusionment with previous false alternatives. Fewer and fewer people are bothering to vote in elections, for example, correctly realising that it will have little effect on their everyday lives.

For more discussion of this question, see Past Revolutions.

Does that mean we have to sit around and wait for a revolution?

No, of course not. We argue that the working class should organise for socialism, but that doesn’t mean that nothing can be done this side of the revolution. Earlier we mentioned the welfare state as a failed example of reformism. But on the other hand such things as basic health care came into being because the working class fought for them (even though politicians have since claimed the credit). Without the threat of action we would never have won such things. Strikes, or the threat of them, help to improve wages and working conditions.

We have the ability to change things if we act together. The power to transform society lies in the hands of those who create everything—the working class. This is the source of our power, should we eventually use it. The power not to make a few reforms, but to change the whole system, to make a social revolution.

Is socialism against human nature?

For in-depth discussion of the question of human nature, see Do our Genes Make Socialism Impossible?.

Also see William Morris’s How We Live and How We Might Live.