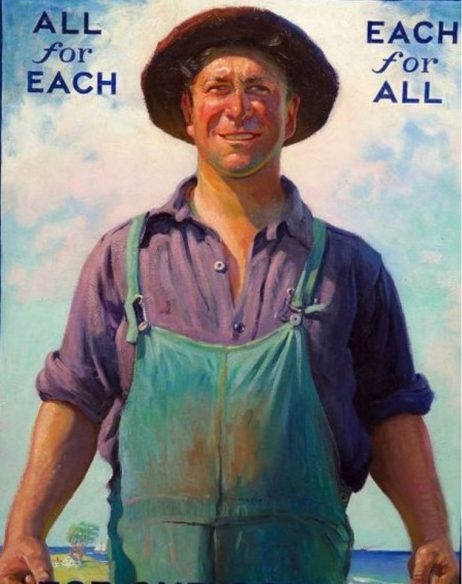

Socialists are often thought of as being concerned with the welfare and interests of the industrial proletariat but as this article shows, the case for socialism also applies to the small farmer.

letters from Alf Budden to a fellow farm slave and comrade in revolt.

“And the fields that gleam, like a golden stream

And the slaves that toil amain

Are thine! are thine! Oh, master mine

To the uttermost measure of gain.”

Foreword

The writer of these letters does not pretend to have covered the whole of so vast a subject, or to have dealt at all in detail with the many questions involved.

They were written at various periods, and under strikingly different conditions, and, in consequence, display a certain disconnection, unavoidable, but perhaps not disagreeable.

Their mission. however, is to stimulate closer investigation of the conditions under which the FARM SLAVES work, and to point a way to emancipation. That is all.

THE AUTHOR.

Calgary, Alta. August, 1914

Preface

Amongst the many problems confronting the Socialists of the world one of the oldest and most perplexing is that of spreading a proletarian viewpoint amongst the more or less scattered and detached agrarian workers The presentation of our case to the wage slave has been a comparatively simple and direct process, the method of exploitation being at once easy of comprehension and stark naked to the most casual glance. With the country slave, however, the position has been obscured by the form of concentration of capital which extracts full measure of profit behind a mask of small ownership of property.

Where the wage worker has but a job, and that only at spasmodic intervals, the Farm Slave has: – ” my land; my horses; my machinery” and the steadiest kind of employment. He is, therefore, deeply mystified and in many cases aggrieved by the first presentation of the Socialist position he may hear or read, for he understands (and truly) that land – in common with other means of subsistence – is to be made the common property of society, and that the Socialists contemplate confiscation of his hard won indebtedness. The unfaltering presentation of Marxian Socialism does not then make rapid strides anywhere and least of all amongst the rural communities. Yet experience has infallibly shown that this is the only possible road to victory. Compromise may bring a big following, a deluded following, which, once having but superficially realized the nature of the deception, will turn and rend its erstwhile gods in an agony of reaction. History has shown, all too clearly, the fatal character of any such procedure. The Socialist Party cannot afford to ignore the great mass of agrarian workers, neither dare we swerve to the right or left in delivering our message. A PSEUDO-SOCIALISM IS ANTI-SOCIALISM.

It is surely well enough known that the fatal weakness of the Commune of ’71 in Paris lay as much in the fact that outside the three or four cities involved, stretched an ocean of ignorance – a mass of peasants to whom the revolutionists appeared as devils incarnate, who were used to beat down and smother the insurrection, as much as any other contributing cause just as, in like manner, the large, rural, anti-taxation membership constituted the clay feet upon which that image of brass, the German S. D. P., was so perilously poised, and which fell back to violent and bloody reaction the moment a real strain was placed upon it.

THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF CANADA, in its treatment of the agrarian question has so far maintained the revolutionary position, counting it more than good tactics to attack the minds and ignore the feelings of those whom it sought to enlighten. Operating, as it does, in a country largely agricultural, and being composed, in the main, of those who having glimpsed both sides of the shield as wage worker and farmer, are enamoured of neither form of exploitation, it has naturally given a great deal of attention to the status of THE SLAVE OF THE FARM.

For some years a polemic raged through the columns of the Official Organ of THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF CANADA, the “WESTERN CLARION,” involving various views and opinions, most of which, however, gradually settled down into two opposing groups.

The position maintained with vigor by the older school was that the farmer stood in the same category as the wage worker, that farm machinery was but an extension of the carpenter’s tool bag or the plasterer’s hoe, and that farmers did not sell wheat, oats or live stock, as such, but labor-power crystallized into these forms.

The younger group, on the contrary, pointed out the impossibility of offering for sale so evanescent an article as the aforementioned, because it was apparent that the commodity labor-power – the thing offered for sale – was not the release of energy, or energy in motion – kinetic, known as labor or work, but was the ability to so perform, the passive or latent energy potential in the physique of the slave. It was contended, therefore, that the commodity, e. g., wheat, was a finished product sold by the farmer in the same way as a merchant sells his goods. And, further, that the view of the farm machine being a mere extension of the wage worker’s tools, was in violent opposition to that very dialectic upon which the Socialist position so impregnably rests. “If,” they argued, “the power loom by growing up, changed not only the form of ownership but reversed its position to the worker, growing from helpmeet to oppressor, why was this not also true of the farm machine?”

All were agreed, however, that the proposition, “He who owns the means whereby I live, owns me” was an undeniable fact and constituted the basis upon which all investigation must rest.

The net result of the discussion seems to have been that after all the real problem which must be solved is the laying bare of the process by which the vast quantities of farm products are silently juggled out of the hands of the operatives into the maw of the capitalist class. This accomplished, it was felt that the task of enlightening THE FARM SLAVE to his real position and class interests would be considerably advanced.

This pamphlet essays the presentation of some facts and figures pointing to that end which may stimulate further enquiry; raise some little argumentation, assist in the process of education, and – pass on, to be replaced by a more comprehensive, concise, and elaborate presentation of further developments, as did the first “Slave of the Farm,” of some years ago.

DOMINION EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

LETTER No. 1

My Dear E., –

The title under which these letters appear will not, you may be sure, appeal to the booster and optimist. “Slave,” as applied to our farmers of this last west, will by no means please the real estate and bogus stock vendor. Journalists and publicity men (as such) will reject with hired scorn and contumely what is written here, should they ever discover the existence of these pages. They, poor fellows, must rave and enthuse over what is not, and directly ignore or forget what is. A miserable lot, and not one to be envied by those who would be free – at least in thought. The leaders of the various farm organizations will deeply regret the viewpoint taken in these letters, despite the pitiful howl put up by some farm slaves at the Lethbridge Convention of 1914, or else feign to regard it as the emanations of one disgruntled Conservative. Old party heelers and workers will find cold comfort, for it is the purpose of this scribe in future letters to place these gentry in the category to which they belong, to prove, if possible, that far from being the Soil Slave’s friend, they are in very fact his worst foes.

But you, who have worked your fingers to the bone; you, who have suffered exile, who have been “filed upon by a homestead,” and who at last gave up in despair; you, who upon many a bitter winter’s day have ridden or tramped behind “dumb, driven cattle,” hauling cordwood for a meagre existence, you will find some explanation, perhaps, why these things be. You will recognize at least that some points are clear where before we were somewhat hazy in our explanation of the remarkable situation that the farm slave keeps producing more, and becomes steadily poorer. You will, I think, realize why the “Slave of the Farm” is a slave, and the way to his emancipation.

These letters, of course, do not pretend to cover all the ground or give all the truth, but if through this medium some other worker can be induced to study the Socialist position, you, I know, will feel glad, and I shall rest satisfied. The business of boosting the West has developed into a science; no effort has been spared to obscure the real state of affairs; no stone left unturned to seduce the nimble dollar from the pocket of the “easy mark.” All over the world the virtues and beauty of the Canadian people, the wealth and quantity of “our” natural resources. the splendor and joy of “our” scenery, and the opportunities for the investment of Capital at high rates of interest have been trumpeted. You will smile, of course, at the idea that virtue and beauty, health and joy, can exhibit as a result of the “investment of Capital at high rates of interest,” but we must remember that many, many of our fellow slaves still have this master class viewpoint. The soil slave himself howls and howls aloud for Capital; he weeps to embrace his most implacable enemy.

Those in charge of the “Ananias” policy of boosting lost no opportunity to play the game. The stranger crossing the continent. the journalist or editor, the statesman or author (if he be of sufficient importance), is induced to take his impression of the Canadian West from the wide windows of the Pullman coach or the deep armchairs of the Canadian Club. His viewpoint is colored by the purple and amber of wines, delicately served.

Wined and dined, feasted and feted, beguiled and bewitched, he hastens home to write a glowing account of Canadian prosperity, or make brilliant after-dinner effusions on Canadian hospitality. The grim story of settling the land, the wretched shacks, the dugouts and sod houses, the suffering of the working soil slaves who are making the West what it is, are most carefully hidden from his view. It is doubtful if he would write of them did he manage to clear his vision from the rainbow hues of choice cigar smoke and rare vintages. He is not trained that way. He will dilate for hours on an abstract “Lady of the Snows.” He has seen the well-laid cities, the peaks of the Rocky Mountains; he has taken drinks with City Mayors, and inspected the experimental farms, and he knows ALL about the Canadian West.

Speeding along behind a giant locomotive, a bewildering panorama of changing scenery is presented by the flying train. From St. John to Vancouver, he sees the hand of man busy, moulding from a wilderness all the elements of modern civilization. Here are churches and segregated districts, hotels and Salvation Army strongholds, associated charities and millionaires, factories and policemen, soldiers and slaves, autos and shoeless tramps, millions of bushels of grain, herds and flocks of sheep and swine, cattle fat and ready for the block, great flour mills and – starving men and women. These latter, however, do not “get into the papers” ; it would not do, you know.

From coast to coast the noise of industry catches the ear. Labor at work building a giant civilization, that it may live in semi-savagery; forging the chains of its own bondage, that masters in Monte Carlo may play the game and never miss their losses. The coming of autumn sets the stage for the grandest scene of all, makes display of “our great wealth” more seductive than at any other time. From Winnipeg west, the country is golden with waving grain and shocked fields. Giant threshers hum and hurl their straw streams skywards. Binders “click-click-click” behind straining teams and sweating “shocking” slaves. The shout of teamsters and the jingle of harness mingle pleasantly with the whirr of countless coveys of game birds, frightened and fluttering from bluff to bluff. Red and russet and gold are the prevailing colors; work – the ruling passion. Far overhead the soaring vault of an “Italian” sky, through which the fleecy cloudlets sail, peaceful and unsoiled, as if in mockery of the sweating slaves below. Low down upon the horizon a smudge of drifting smoke – tractors at work. Over yonder the faint hum of a roaring freight. Well might the gods of agriculture feel glad; small wonder the wretched shacks of the farmers seem to hang their heads and crouch down, shabby and forlorn, amid such a ruck of wealth.

The slave himself is impressed, as you well know. How many times have you and I laughed about it. How many times has that hope which springs eternal, risen even in our breasts, as we gazed upon the ruddy splendor of labor’s creation? How many times remarked: “That now we have such a good crop, things will be easier”? How many times have we been deceived? You know we had strange notions of our giddy selves. We talked about “our country” and “our crops” for all the world as if we owned them. There are thousands still who so believe; even as they work, threshing the crop, they have forgotten the strenuous labor of the last few months, the weary days and nights watching the sky for hail or wind. They have no memory of last year’s experience how, somehow, the crop leaked away and left them still poor. The countryside is red with shocked grain, the powerful property sense awakes in him again, the shadow of a substance long since passed away; the idea of old time peasant proprietor mingled with the Capitalist property notions culled from newspapers. He has forgotten, if he ever knew, he is a slave. He is fellow with Donald Smith, co-partner with William Van Home. He will sing the siren song of prosperity, if questioned by a stranger, himself standing in his wretched overalls.

Small wonder the matter is easy for the publicity man. To persuade the people of other lands, that here is a free and happy people, is no difficult task under these peculiar circumstances. The man in the Pullman has, after all, some excuse for his ignorance when the farm slave himself survives to conceal his real condition, even to himself.

That which neither seems to understand, however, is the meaning of the coming of Capital, and no doubt it is hard if you persist in taking your ideas of economics from the newspapers. The significant fact that side by side with the coming of the Pullman, with those shining rails over which the train glides so swiftly, those straight ruled farms, those slim uncanny elevators, this freight train loaded with machinery, the death blow to liberty was for the time being dealt. You, my dear E., will see this quite readily: alas, there are so many who do not. It seems a most flagrant contradiction that the farm slave is a slave because of toil-saving machinery. It seems absurd and an unthinkable thing, that the coming of machine industry should render its operatives the more slavish. It requires quite an effort to realize that under Capitalism – because these things are Capital – the more they tend to saving labor, the more intense and prolonged that labor becomes. Yet this is in very fact true. No sooner does a railway enter a farming community, than a howl is raised for another line to relieve the people from the exactions of the first comer. The great threshing machine is but an iron chain to bind the slaves of the farm closer to the masters who exploit them; farm machinery but whips and scorpions to torment them.

And now you will hear someone exclaim: “Are the Socialists then opposed to the coming of a machine? Are they new Luddites? Machine breakers? Reactionaries? Indeed, No! We welcome all human inventions to displace labor. Our quarrel is a matter of ownership. Shall the machine master us, or shall we be its master? Shall the owners of this machinery, a small class of parasites, continue to hold these things so vital to our existence? “He who owns the means whereby I live, owns me.” And, of course, as we shall see later, the farm slave’s “ownership” over means of production is a colossal, if somewhat grim joke. To hear the tattered homesteader talk of “my farm” and “my machine” is a thing over which the gods must need laugh.

LETTER No. 2.

My Dear E., –

You may ask by what means does capital arise and why do the Socialists ascribe such malignant propensities to it. Others, how did it first come to this country, since, once upon a time, there were only Indians and gophers, as the saying goes. The story of its rise is too long for us to tackle here, but its genesis is written in the annals of history in “blood and fire.” The most frightful loss of life, the driving out of peasants from their ancestral homes, the burning of homesteads and death of whole villages. These are the scenes out of which the capitalist class rose, Phoenix-like, to glory. Do you suspect it was otherwise with this continent? True, the romanticists are forever telling us the great story of Empire building. They do not always tell the truth. To them it is one long source of heroic tales and epics. This is not altogether without foundation, for there were brave deeds, but also bloody. Heroes, in the cause of trade, must always be practical, and never miss the main chance. And it was so with the first attempt to colonize the New World. An epoch making era it was when on a summer’s day the frail bark of the adventurers rounded the Pebble Ridge, or dropped, amid the report of saluting cannons, down Avon, past Bristol port, and so out upon the tossing main. “Westward Ho!” and “hey for the Land of Gold.”

Cold was the lure; wealth (and the struggle for its possession) has ever been man’s master. It is the dynamo of human society. There were weeks of terrible privation, of mutiny and murder – alone upon the tossing waste of sullen sea. Would the sea never end? Were they even now sailing over the edge of the world? Who knows! Turn back, sailing master, put her about for home! As unlike any band of heroes as well might be were those crews of gold-hunting humans set afloat in veritable coffin ships. The poet sings of “regions Caesar never knew,” heritages of Britain, and these regions discovered by the sea captains of the Middle Ages, indeed show quite plainly that no iron yoke of civilization had ever burdened the dweller in this New World. No Caesar had ever come to fill the land with triumphs of art and slaves; to build great cities where the wealthy might revel and the worker rot. To these new Romans fell the task of bringing to the western shores all the benefits of Christian civilization. With torch and brand they pressed upon the Indian. As their progenitors – blood-stained clansmen of the Tin Islands – fought and died, hurling their naked bodies in vain against the mail clad might of the Roman legionaries, so these new Romans, also in mail, swept the naked red man from his ancestral home. Foot by foot, mile by mile, the bronze-skinned warriors contested the right of entry. Kings in England or Spain granted charters of eminent domain, others trusting but lightly to such clerk’s tricks descended bodily upon the Indians’ homeland, and made good those charters with musket, sword and sacrament. Those were evil days indeed! Dark and bloody were the actions of the “whites”; terrible deeds perpetrated in forest grove or rocky glen; evil happenings that blanch the cheeks of the raconteur and send the children cowering to the blankets on a dark night, even to this day. For there was gold, gold, gold – mountains of gold; lakes whose glassy surface reflected the bright sheen of boundless wealth hidden in their depths.

Druids in the British groves cursed the coming of the Roman Empire builders, and spat upon the faces of their gods. Medicine-men in the long houses of the Iroquois or solemn aisles of spruce and pine, cursed these new gods of rapine, these new Empire builders, and, cursing them, fled evermore into the hinterland. But what then? Before the swift pursuit of treasure hunting whites; before the faces of Raleigh and Smith, of Frontenac and La Verendrye; at the devastating touch of Cortez and Pizzaro they perished and passed away. Caesar in his conquests “made a desolation and called it peace”; these new Caesars desolated and knew not peace. For this is the method of Capitalist development. Before the blighting hail of European firesticks, the great game animals vanished from the lands. The plains were putrid and stank to heaven, telling of the ruthless pillage of nature’s hoards. From Sandy Hook to the Golden Gate, as time progressed, the robber white made his way, and the bones of those who blazed the trail, together with those who tried to erase it, littered the boundless prairies, or shone stark upon the mountain passes.

Meanwhile another wave, northward and westward, from the frozen shores of the Hudson Bay, from the wide and majestic St. Lawrence, through the great forests of Lower Canada, around inland seas, heading past Superior, undismayed by rapid, rock, or Indian – the pioneer pushed his way. The strident voices of a hundred Red River carts proclaiming their advent, they came at last to where the City of Winnipeg now stands “and behold it was a fat land” so, being a canny folk, they drove in their claim stakes.

Thus far the forerunners of capital swept, but now a sudden halt. The advent of capita1 itself had to await the process of its own development, but it lost nothing by the delay. True to its inner self, when once its requisites were to hand, its methods of exploitation were no less vicious, if more refined. Many factors, including the hostility of the Hudson’s Bay Company, were responsible for this petering out of the westward surge. But an unsurmountable difficulty met the settler. Cyrus McCormick and his friend Appleby, were not yet to the fore; the coming of modern machinery of production alone made possible the colonization of the great prairie provinces. True enough, people drifted in after the surrender of the Hudson’s Bay right of domain, but the next great wave did not come until the trap was ready.

McCormick’s great invention fell, of course, into the hands of the Capitalists – all machinery of production is theirs by right; the capitalist class is the child of the Machine Age, and since it owned the key to unlock the West, is it possible to suppose that in unlocking it, it did not first ensure itself? Here were possibilities of fabulous wealth, all that were needed to develop it were slaves enough and machinery of production. Of course, this did not develop all at once as we have said before. The exploitation of the West waited on the development of machinery. With the appearance of the first binders and larger machinery, a systematic campaign of immigration was started. The appeal to the dispossessed of Europe to come west and build a free nation on free soil fell upon fruitful ground indeed. The response was sudden and overwhelming. Here was land, – land and freedom: “A man might become his own master in a year or two.” “Banish the boss” was the slogan. “Look what 160 acres in Germany or England mean” they would cry. “why a man is a little king with all that land!” Feverishly they would pace around some public square, calculating how many acres there were in it, and then in their mind’s eye, the grime of a smoky city would give place to green and golden fields, wherein a snug dwelling rested, cuddled down on a slope by a gently winding river. They came in thousands as their sires came in hundreds, but they did not find the same conditions. The process of developing the West has been a reversal of the historic method. In Europe, Capitalism fought a bitter war with the landed classes. In Western Canada, all chances of war were forestalled; capital was ready and waiting to harness its victims to the soil. They never became a landed class, all they could be were soil slaves.

Great masses of these have not yet, as you are well aware, discovered this; they are still thinking in the manner of their fathers. The SLAVE OF THE FARM hangs most stubbornly to the idea that he is some kind of a freeholder or capitalist. All the farmer’s organizations are founded upon this idea; his papers and his conversation betray this false, or rather old time, conception of his position in modern society. Ancient ideas die hard. There was a time when the holding of land meant all the difference between slave and freeman, between noble and chattel. The most severe punishment – almost as bad as death itself – was to be branded “outlaw” or “landless man” by the communal dwellers of early England. A landless man was a proscribed and hated wretch, every man’s hand was against him, and who caught him foul might enslave him forever. Even as late as 1547 any person could make one of these poor unfortunates bondsman for all time by simply denouncing him as an idler, brand him, starve, whip and torture – even execute him. To be a landless man was indeed a terrible thing.

The early settlers of Canada knew this too: the possession of soil meant to them life. Composed of United Empire Loyalists, French Hugenots, expatriated Irish, and dispossessed Scottish Cottars and Clansmen, the social ideals of the peasant proprietor necessarily grew up amongst them, and are retained today by this new wave of immigrants, alas! to their utter confusion of thought upon matters pertaining to their economic status. The “back to the land” movement holds the imagination of the British worker because he knows the strength of the landed classes in his own country.

There is also another factor in explanation of the soil slave’s viewpoint, which, my dear E., must always be kept in mind, – the topographical condition of the country. This plays an important part. The voice of the wide spreading prairie, the murmur of the whispering woods, the gurgle of the swift running creek or the majestic sweep of some giant river, the wide expanse of the vaulted sky, and the presence of wild things, proclaim the song of freedom; live again the cry of the past; wake again in the mind of the Western farm slave, the saga of the soil. The sense impression of communal barbarism, or the sturdy thought of the peasant proprietor linger here where capital is master; have stolen from their graves to whisper of the freedom that is no more.

And Capital which exploits all things is able to bring to its aid the make-up of the human mind. The abstractions of today were the sense impressions of yesterday. To the peasant proprietor, work was well worth the doing. The products of his hands accumulated around his homestead. Wealth he produced, but not commodities. Modern Capitalism manages to retain among its slaves of the farm the ideas upon work in vogue in those days, while skilfully abstracting the produce of that labor. No more do the products of the dweller on the land store up and accumulate with him. Swiftly are they drawn away; they have become commodities. All that is left with the soil serf is enough to keep him in slavery, and the passionate desire for work; heritage of the past. All too well did the capitalist realize the truth of their economist’s words, that “small property in land is the most active instigator to severe and incessant labor . . . . . .” All too well have they been able to harness this to their own aggrandizement.

LETTER No. 3.

My Dear E., –

You are now fully aware of the position we have been trying to establish, that the coming of the great machine industry “dealt the death blow to freedom for the time being,” and that, nevertheless, the farmer, long since dispossessed from the rude

but plenteous position of small owner, still hangs on to the ideals of that happy period.

The reason for his degradation we place at the door of capital, of machinery of production functioning as capital, and now it is time to explain just what we mean when we speak of capital, and who are its possessors, for the farm slave, comical as it may appear to you and I fondly imagines that he is the owner of this “key to all things desirable.” “Have I not land,” he will cry, “and machinery? Is not this capital?” And indeed it is, but alas for him, he is owner of neither. The benefit of capital comes to its owners; that is why the capitalists are wealthy beyond their wildest dreams. The beautiful things of the earth are theirs, the choicest of labors’ creations, the servility of the Courts, the subservience of the press; the parliaments are but their executive committees; the soldiery, police and judges their obedient slaves.

Can this be said of the Western Farmer? Absolutely no! All these are arrayed against him. Even from his own mouth is the absurd notion refuted, for we read in page 7, Resolutions submitted to the United Farmers of Alberta Convention, January 1914. at Lethbridge:

“Whereas the farmers do not have sufficient time to dispose of their grain between threshing time and October the first, in order to raise money to meet their implement notes, which come due on said date; and Whereas a great hardship is imposed upon the farmers by being COMPELLED to haul their grain out so early in the Fall, thus depriving them of any time for fall plowing. . . . Therefore, be it Resolved that Local . . . . petition this Convention to use its influence with the implement men to induce them to change date of payment to December First.”

And again:

“Whereas the machine and implement companies urge farmers to buy. . . . . and when once they have the farmer’s name to paper, crowd him without mercy: Therefore, be it Resolved that we recommend all farmers to buy no more machinery or implements for the next twelve months.”

That they are compelled to haul their grain does not sound as if they stood in the same class as Patten or Guggenheim, does it? Of course, it would make no difference if the masters would shift the date of payment, the compulsion would be just as urgent, for the capitalist has the power to “crowd” the slave “without mercy.” It is indeed the function of capital. Just how oppressive this power has become is shown by a cutting from a Calgary newspaper dated December 24th, 1913, in which it is stated that “so bitter has the feeling become between the farmers in many parts of the Province of Saskatchewan and the collection companies, that the Attorney-General will in all probability have to interfere, as acts have been performed within the last few days that could be classed as little outside of sedition . . . The farmers have got together and formed a fund to pay the fines of any farmer found guilty of assaulting the collection agent of any implement company . . . In the last three days two assaults have been made upon collectors, resulting in a fine of $10 and costs, the fine being paid out of the fund.”

This is as unlike the actions of a bunch of capitalists as possible. These poor slaves, banded together to resist the robber power of the masters, are guilty of “something like sedition,” because they wish to retain enough to keep themselves alive. Their capitalists, my dear E., when they wish to resist payment, do not band themselves together to assault collection agents. They procure an injunction or finance a lobby, and are obeyed in direct ratio to their financial standing, and they are branded patriotic according to their thieving capacities. ‘Tis only the slave who is seditious, for it was ever a crime to resist starvation by trying to retain a little of that produce which belongs to the owners of capital. As witness! The newspaper quoted goes on to say: “George Moore – who no doubt fancies himself a capitalist – ( the inset is mine) a thresher of Alask had to pay ALL his season’s earnings back to the implement company from which he bought his outfit. When his men sued him for their wages, he had to go to jail in default of paying them.” A pretty capitalist, forsooth! Who ever heard of capitalists slaving and starving as these farm slaves? Who ever saw capitalists’ wives going gowned in gingham and such shoddy raiment as these farm women wear? Who ever heard of an owner of capital following a weary round of threshing, and then landing in jail after having given “all his season’s earnings to the implement company”? How bloated we felt, you and I, when we surveyed our capital over there at North Battleford, did we not? What fine raiment and sweet wines were ours? And yet the machinery and land are there, and the farm slave sometimes sees title deeds to that property, so we shall need to go deeper and explain.

Let us take machinery first: The Socialist definition does not include small items such as carpenter’s tools or a gardener’s hoe, but only that great social machinery of production, mills, mines, factories, railways and land, in short, those things the workers must have access to in order to live. I presume no one will be foolish enough to come forward and deny that these things are capitalist property, although some disagree as to who are the capitalists.

We see, then, that the farmer is surrounded by enemies which he, himself, recognizes. He is acutely aware that because the masters own the railways, mills, elevators, factories, shipping, etc., they hold a gun to his head and cry: “stand and deliver!” But what he has not seen is that, because they own all these things, they own all the produce of the soil, nay, own the very farm and its machinery.

We have said, in a previous letter that the settlement and exploitation of the West was not possible until the invention of modern machinery of production, and a moment’s reflection will show us that this is all too true. The division of the West into quarter sections, has a deeper meaning than most think of. The manufacturers of the East, having erected a tariff wall next proceeded to make the home market as large as possible, and it will be clear to the greenest homesteader that more machinery will be used to work four quarter sections than to farm one section. To fill the west with people using primitive tools would have meant nothing at all to the interests that were already, as early as the beginning of the last century, reaching out for the ownership of labor’s product. Indeed, they would have formed, as did the settlers of Upper and Lower Canada, the greatest stumbling block to the growth of capitalist fortunes.

The economist, Wakefield, gives us the master class opinion of such a state of affairs, when he calls it a “barbarizing tendency of dispersion of producers and national wealth.”

Marx, quoting Wakefield, speaking of the Atlantic shores of America, says: “Free Americans, who cultivate the soil, follow many occupations. Some portion of the furniture and tools they use, is frequently made by themselves. They often build their own houses, and carry to market, at whatever distance, the produce of their own industry They are spinners and weavers; they make soap and candles, as well, as in many cases, shoes and clothes for their own use. In America, the cultivation of the land is often the secondary pursuit of a blacksmith, miller or a shopkeeper.” And Marx adds the query, “whence then, is to come the internal market for capital?” In other words to fill the West with producers for use, who would consume the produce of their primitive industry, was not an alluring prospect for Canada, and furthermore, could not have been done. The great prairie country west of Winnipeg was to be made “that internal market,” and care was taken to insure this desirable result. The Donald Smiths, the Harrises, and the Masseys, the Jones’ and McDonalds, the Petries and the Houstons, the family compact, and the “Johnnie A” fraternity; these gentry framed things for the settler of the West, and did it well. The land and machinery laws reflect as much upon the skill as the barbarity of their framers.

That George Moore languished in prison December 1913, for working his best, and surrendering his all to the machinery company, testifies as much to the freedom of the Canadian citizen, as to the intelligence of the slaves, who continue to vote for this state of affairs, who support, by all means in their power, the rule of the robber capitalist class. It points us to the inevitable conclusion that this farm machinery is one of the means whereby the masters fleece the slaves; show us all too plainly that the slave who fancies he owns it, is, in reality, in no better position than any other worker, manipulating the machinery of production for a parasitic class, which owns the proceeds of his toil. Indeed, after the passing of the Farm Machinery Act (which of course was not designed to protect the farmer, as we shall see later) the machine masters put the position up to the slaves in no uncertain manner, as the following circular letter will show:

“Dear Sir, – “We beg to advise you that owing to an Act entitled ‘The Farm Machinery Act’, we feel that we can no longer safely do business in the Province of Alberta, and have decided to close our Calgary Branch, and ship all machinery and repairs to our Regina Branch. “We will sell no new machinery in Alberta, and as regards for repairs for machinery already in Alberta, it will be necessary for customers to order them from our Regina Branch, and accompany the order with a remittance by Express or Post Office Order to cover the amount of the repairs ordered. “While we regret the inconvenience and delay which this will probably cause customers, yet there is no other course for us, with the present law in Alberta. “Yours very truly, NICHOLS & SHEPARD COMPANY, By F. C. Higgins, Mngr.”

Which simply means, “If we cannot have your whole hide, we will not bother with a part thereof.” For that was exactly what brought the Sifton Farm Machinery Act into being. Aside from its political aspect – and of course it served as a powerful election weapon coming into effect, as it did, immediately before the 1913 election – it was an instrument designed to render more equitable the division of the spoils amongst the spoilers who of course were and are grouped roughly into three divisions: Machine Companies, Banks and Mortgage Companies.

APPENDIX TO LETTER No. 3.

30th April. 1916. The Machine Companies sole aim is to unload their property as fast and as securely as possible; their all too generous “credit” system merely requiring that all a “creditor” need have was habitation on a homestead. The velvet tongued sales agent canvassing the farmers is succeeded by a horde of especially handpicked bullies called, for want of a better name one supposes, collectors! These gentry, armed with all the powers of a properly constituted bailiff and bulging with an overwhelming display of legal shackles, chattel mortgages, etc., endeavor by all possible means to induce the victim to sign his name to what they are pleased to call “security”, in fact documents so ironclad and so well devised to “protect the interests of the vendor” that the signer finds himself and family bound to the service of the Machine Companies with chains more galling, because less visible, than those which covered the limbs of slavish antiquity. The results are usually secured by what has been aptly termed “bulldozing” and indeed the psychological side of the performance is almost overdone, the collectors undertaking to conduct an inquisition as brutal and disgusting as any “third degree” examination ever staged. How old are you? Where were you born? Are you married? If so how many children? And – crowning piece of blatant cynicism: Are you prosperous?

The victim’s ignorance, or his well grounded fear of legal processes are ruthlessly used to coerce him into “placing his hand to paper” with such dire effects that he frequently finds himself homeless, cast out of what little shelter he may have to start life over again. Small wonder then that there now and then appears spasmodic turbulence such as that “something very like sedition” which we have seen burst out in Saskatchewan. His blundering psychology, however, hopelessly floundering between the deep-seated hope that one day perhaps he will sit amongst the mighty in the land, become in fact an arch exploiter, and the well founded fear that they will get him yet, coupled with his total failure to grasp the true nature of the game, drives him to willingly support by voice and vote the very system of exploitation which makes the foregoing disgusting state of affairs possible. He wallows before his master while “beating up” that other slave sent to torment him. Under these circumstances it is of course no trick for the Machine Companies to maintain the perfectly masterful attitude that although “The ownership of this machine remains vested in the vendor” nevertheless, by some legerdemain, it is at the same time the property of the victim. Indeed there are numerous cases where, through faulty design or unskilful assemblage, machines, absolutely worthless, mere collections of scrap-iron, were foisted upon the farmers – quite innocent of course of the nature of such things – despite which the Companies involved used every means, outside recourse to law, to compel the slaves to retain and “pay” for them, even going to the trouble of ferreting amongst the neighbors for any weak spot in the honesty or industry of those whom they had ensnared and this with the full knowledge of the condition of the machines in dispute.

Mr. P. P. Woodbridge, general secretary of the U. F. A., and a most enthusiastic supporter of the Capitalist Class, is nevertheless compelled to substantiate the above in his yearly report before the Calgary convention in 1916. He cites the case of two farmers who, to quote one of them, “would certainly have been ruined” had not the organization fought the matter out for them. One victim “In July, 1914 . . . purchased a steam threshing outfit from a certain implement company, which, however, failed to give satisfaction, and in fact WAS UNFIT FOR USE, and after prolonged negotiations, the machine was eventually removed by the company, who, however, FAILED TO RETURN THE MORTGAGE PAPERS AND NOTES WITH WHICH AS USUAL the purchaser had burdened his land.”

It should be pointed out, however, that these cases occurred in Saskatchewan, and not under the jurisdiction of the Farm Machinery Act.

It was felt that the one party of exploiters were “comin’ it a bit thick,” and that some measure of protection for the animal who produced was necessary else he was in danger of being extinguished altogether. A most shocking thing to contemplate, from the view point of the other two, who kept no collectors, but were acutely aware of the economic truth that vacant, unworked land was worse than useless to those who looked for interest on Capital, and that profit grew not upon trees, like pears.

The Farm Machinery Act, then, fulfilled this long felt want, but you are not to imagine, my dear E., that the task of stalling off the vampire fell to the other twain, by no means. The burden of proof was placed upon the grain raiser. He must take the matter into court, must expend money and time to the end that he might assist at a more equitable division of his hide, that if he won, . . . if he lost? Well we are all aware of the fate that awaits the poor slave who comes under the ban of our Courts of Justice. Are we not?

LETTER No. 4.

My Dear E., – The separation of the worker from his tools has been the historic mission of this great system of production; the continued gathering of them into factories and their continual improvement in productive power, have, while enlarging the stream of wealth in the form of commodities, also beggared the worker. The trick was easily turned in other branches of industry, but the turning of farming into an industry and the separation of the small owner from his tools of production took more time and skill. Yet it followed much the same course.

Before the coming of great machinery, the artisan was a most important person. Today, when children and women, by pulling a lever or turning an electric switch, can duplicate the most skilful product of the hand worker in a fraction of the time used up by a craftsman, that artisan has, perforce, to listen to the owner of the machine, the capitalist, and become his slave, for wages.

On the farms of Western Canada, the same result has been achieved, but by slightly different methods. In the days of the crooked stick, the wooden plow, the harrow made from some untrimmed log, the cradle and the reaping hook, when cleaning grain was done by throwing it into the air on a breezy day, when the muzzled ox or unbroken pony threshed the grain, the incentive to separate the worker from his tool was not very great.

The masters today are forced to own the machines because they who own the machine own the product, but in those days, since the product was almost wholly consumed by the producer, at least in Eastern Canada, capital had not much to lay hold of. In the year 1840, however, McCormick placed upon the market the first reaper, and a new era opened for farming. You will notice that as the spinning jenny “grew up” and became a great power loom, so its ownership changed hands, that it developed from a tool of production for use, into a machine of production for profit. So also the machinery of farming. One other thing: that as it grows larger and larger, so does its very nature change. The forked stick was an individual tool, as was also the wooden plow, but the great modern plow is a strictly social product, a social tool. So also a point is reached where from being the property of an individual, it becomes the property of a Class. It becomes – capital. Even the nature of the products change. From products for use they become, with the enlargement of the machine, with the social production of the tool, social products for exchange – commodities. So also changed the social standing of the dweller on the soil. From being the owner of a farm and number of hand tools, he becomes a slave harnessed to the social machinery, producing a great stream of wealth for masters he has never seen. And here is the secret of the poverty of the Western farmer.

As we pointed out, he never was an owner of means of production – a peasant proprietor. Capital was ahead of him, and the laws of capitalist development go their way no matter who suffers.

The farm slave himself cannot fail to notice that every new machine has this tendency – to cover more ground in quicker time than heretofore, and to become larger and more expensive. We have mentioned commodities, and this brings us to the crux of the pamphlet. Why are the machines growing ever larger? What is the reason for the continued effort to do the job quicker? What is a commodity? What do we mean by social production?

To take the last first: The farm slave is not a producer of farm products. That is, he cannot do this alone, he must have the aid of the rest of the workers. Imagine starting to farm without a binder, a plow and a seed drill, think of raising hogs without parents, imagine building a shack without lumber (unless a sodden or a hole in the ground). Just stop and look at your binder and realize what it is – an embodiment of social labor. Imagine (if you can) how the whole of society bends itself to the task of producing it. Even in its makeup are the farm products raised by some farmer elsewhere, that went to feed the workers who gave their toil to create it. Try to trace it back, and you will lose yourself in a maze of industry. Such remote things as brick-making and tailoring are involved in its construction, for you know, the binder was built in a factory made of brick, and the worker had to be clothed. The farmer becomes a cog in the great machine of industry, no more important than the rest, no less so, all bending, however, to produce a stream of wealth they do not own. That is social production and, upon this fact, the Socialists base their demand for social ownership of those machines so necessary to the life of society.

This is the first requisite for a commodity; that it be a social product. Next, that it be produced for exchange or sale as in opposition to a product for use. Of course, this commodity must have a use value, but there is no farm slave bold enough to claim that he raises wheat today for the world’s use, else would all the hungry be fed, and we know under this system of production, this is far from being the case. You and I did not figure on the amount we were raising according to the number of people it would feed, but how much money we should get from our masters for raising it. We went to work to raise wheat as we would go to work in a factory, to get money to buy other things, and just in the same manner does the capitalist who gets that wheat, look upon it solely as a means of increasing his wealth. He would just as soon cause to be manufactured ladies’ fans or monkeys’ collars. It is all the same to him, so that there is a brisk demand. In old days the peasant packed his grain to the mill and brought it back flour, a product for use: Today the farm slave hauls his masters’ grain to the elevator, and sees it no more, neither does he trouble to enquire what becomes of it. He has had what he raised it for, the medium of exchange – money – and he is satisfied. A commodity then, is an embodiment of social labor and raw material produced for exchange.

Now for the last question: Why are the machines getting larger and larger, and what is the meaning of the continued effort to do the work quicker? How shall we measure the value of a bushel of wheat? Why is it One Dollar or Sixty Cents, as the case may be? Upon what basis is this calculated?

Quite lately the farm journals have given much of their space to discussing the cost of raising grain, and close scrutiny of this discussion reveals the fact that about $10.00 is the average cost of producing one acre of wheat. The Government blue books for Saskatchewan also added the weight of their authority to this testimony. Now just what does this mean? How shall we measure ten dollars? What do those figures, impressed upon a gold disc or printed upon a piece of paper, convey to our minds. Let us follow this ten dollar gold piece to its source, remembering that the paper note is but a token. Ten dollars will be a certain weight in gold, and gold is found in the earth, but the centre of this globe may be of solid gold, and yet quite valueless if that which makes the ten dollar gold piece possible, cannot get at it – human labor. Gold must be dug, stamped, refined and milled; great machines built by labor are used in this process; men must work at these machines. In other words, labor, and raw material must come together to produce this gold piece. How shall we find out what quantity of labor is required to dig up and refine and stamp a ten dollar gold piece? There is only one way – in time. That is the only way labor can be measured. One cannot weigh it, nor use a yard stick. Let us suppose it takes ten hours to produce $10 in gold, then the fact that it cost $10 to produce an acre of wheat means that it takes ten hours of social time to do so. That is all. The value of the commodity wheat is measured by the average labor time it takes to raise a bushel.

Now we see the reason, my dear E., why the tendency of machinery is toward bigness and swiftness, for every new machine that comes into use to get over the land quicker reduces the time necessary in production. In other words reduces the value of the product. It seems rather comical – does it not? – that the farm slave should expect a raise in prices, or at least that they remain stationary when the fates have decreed that his every effort shall be towards reducing the value of these commodities. For today, wheat, sausages, gold or corn plasters, are commodities – things produced for sale, and in such a system the cheapest must win, for that is commodity law.

There are other factors with which we shall deal in a future letter, but here we must mention the chief agent in the derangement of price. Now, price at bottom is value, but, because of the blind and unstable frenzy of production, price is driven high above or far below value. If the market is flooded, prices are down, if any particular commodity is scarce, prices are up, but an examination of prices over a period of years will disclose the fact that these wave crests and troughs on the ocean of production, act in the same manner as the salt sea waves. They return to a mean level – value, the cost of production, which can only be measured in labor time. This is the most important point of all. Study it well, “SLAVE OF THE FARM.”

It is, of course, apparent, and goes without saying, that with the increasing bigness of the machine, grows also their costliness, and it is here that the farm slave meets his Waterloo. It is here that the ownership of the machine is proven, if at any place. We have seen that the measure of value is labor time, so that the price of a binder offered at one hundred and eighty-five dollars ($185.00), means that you can get it for that amount of labor; that the farm slave must deliver to the company one hundred and eighty-five ($185.00), or somewhere in the neighborhood of one hundred hours of labor – basing this labor on the average productivity of labor in general – in exchange for this other commodity.

Now, if instead of the binder we extend this to include all the machinery and power necessary to work the average farm (half a section) , say $2 000.00 with the usual interest at eight or ten per cent, we have some notion of the burden he carries. These notes (the company prefers to do a credit business) extend over a number of years, in the case of large machines, to six years, so that in signing them the farm slave actually signs away a portion of his labor, in other words, so many weeks, hours, days of his life, in fact, this is a contract of bondage, and such iron laws did the robber gang indite before the West was opened up, that there is no escape therefrom. One hundred and eighty-five dollars ($185.00) of a certain length of life does not satisfy the vampire capital; the interest is a method of stealing a little more all the time.

The larger the machinery grows, the longer must he toil to obtain it, until a point is reached, where the last vestige of independence drops off him, and he reaches the status of a wage slave, or at best, manager for a machine company.

You know it is a common jest in the country – if a cruel one – that a threshing machine is a “half a section on wheels.” Now, it will be objected that the farm slave pays for the machine at last, and so he does sometimes, but by that time, it is worn out, and he must get another, so that instead of the farmer being an owner of machinery, which is capital for him, the machine has become fixed capital for the machine companies, placed in a factory, whose rooftree is the sky.

Another aspect of the case calls for attention: Let us remember that the essence of capital is that it brings profit to its owner. Now profit is something for nothing, made by buying labor power, and setting it to work upon machinery. For example, if I buy labor power at two dollars per day, and the slave whom I purchase, produces eight dollars worth of value, the profit will be six dollars, less other running expenses. You will see, my dear E., that it is quite impossible to make a profit out of yourself; that you cannot buy your own labor power, and set it to work to make a profit from your own hide.

Since capital is the means of extracting profit from others, the idea that a farm slave is a capitalist meets with a fatal objection. Of course, profit cannot be made out of a machine either. If you give one hundred and eighty-five dollars ($185.00) for a machine, one hundred and eighty-five dollars ($185.00) only will that machine transfer to the product when it is used up. In numberless cases, however, in the West, it does not get used up, the capitalists taking it back from the slave who was working it, before that time. In fact it would seem that those who owned all these privileges, and were masters of all things, were also master of the farm slave and all that appertains thereto. It is remarkable (is it not?) that those old ideas we spoke of in a former letter hang so tightly, but patience, my dear E. a rumble of revolt runs through their ranks. Let us hope it takes the right direction.

LETTER No. 5.

My dear E.,–

In a former letter, you will remember, we spoke of the pillage of nature’s hoards, and tried to show that the early stages of capitalist production always display a marked desire to destroy everything in sight, regardless of consequences, even to itself.

It was so with the first stages of industrialism in England, Europe and America. Asia is now feeling the devastating touch of this most ruthless of all methods, and you are no doubt aware that the Turkish and Chinese revolutions were caused directly by the power of capital.

We have mentioned that Canada could not escape this burden: nay, was carefully prepared to yield that “average rate of profit,” which is the “Ultima Thule” of modem industry. So terrible has become the pillage of the West, so vicious the methods employed, that the Canadian Council of Agriculture (a joint committee of all farm organizations) found it necessary to warn the government a few months ago, that the country was being de-populated, it being quite impossible for many farm slaves to stay upon the land any longer.

This has produced throughout the West, a state of things almost unparalleled even in the shocking records of modem industrial development. Where five years ago, one was met at the door of a squalid hut or shack by a bachelor homesteader, or poorly dressed wife of a struggling farmer, today sweet silence reigns, and the proud stink-weeds, or yellow mustard, flaunt their heads over the ruins of this prairie “home.”

This startling state of affairs has impressed itself upon some other interested parties, with the result that an investigation has been started – a Royal Commission to discover, if possible, how it came about that collections were so small and so expensive to gather in, also just why it was that investments in Canadian securities were not so brisk as formerly.

The result of their meditations, my dear E., threw a little light upon “farming the West.” and incidentally proved the Socialist contention that LABOR, APPLIED TO NATURAL RESOURCES, IS THE SOURCE OF ALL WEALTH.

The methods of modern capital are the same in farming as in any other avenue of production. If in a given spot the productivity of the slaves falls to such an extent that the rate of interest is below the average, capital will be withdrawn, and invested elsewhere. There are two methods of investing money in farming, one is to establish (as was done in the prairie provinces) a large number of small farms, and to place slaves thereon under the guise of freeholders, or to go into the business directly, and on a gigantic scale, employing wage labor after the manner of any other industrial concern.

The former method no doubt had its advantages; it created “that internal market,” while fostering the idea of freedom amongst the farm slaves. There were not so many risks to capital, for no matter if crops failed, or slaves died, the mortgage covers his heirs and successors forever, and, a failure to deliver the surplus created with the masters’ machinery, resulted in the slave’s expulsion, the surrender of his title deeds, or the garnisheeing of his wages, should he desert the farm, and try to gain a living in other walks of life. Those safeguards are not wanting which that coy creature, capital, demands before she will come round and be friends.

But alas for the masters, all things change, and the very methods by which they accumulate such enormous wealth, proves their undoing. You will remember that in a former letter, we spoke quite briefly of the tendency to reduce the cost of production, and explained the introduction of larger machinery and more scientific methods, showing that these factors were becoming more and more fatal to the small farmer, and in order to understand this, we must examine more closely the channels through which the investors of capital realize their returns, for we know full well that no person would surrender the proceeds of a year’s work and permit himself to live in need, were there not some powerful goad behind him, least of all not the soil slave, for there is no bigger kicker in existence. It is a thousand pities that his hoofs are not directed in the right direction.

The great mass of the farmers of the prairie provinces are engaged in raising grain. Wheat being King, we shall need to examine just what happened to the really enormous output of the West. We saw that wheat was a commodity, and that its value was measured by the amount of social labor necessary for its production, and we pointed out that this was a most vital thing – indeed, was the pivot upon which all the rest turned. Were it not for this, the exploitation of the Canadian farm slave could only be accomplished by the direct method of wage slavery. Indeed, did enough of the farm slaves understand this law of value, the capitalist system would be no more. Remember also, my dear E., we made a bold guess that the cost of producing wheat was somewhere near sixty cents per bushel, and now comes forward the Royal Commission on Grain Markets, Saskatchewan, 1913, and establishes the proof. Fifty-five cents per bushel on the farm is the price given by this body of investigators. Now in 1909, the cost of production was approximately forty-eight cents per bushel, and the average return eighty-one and one-fifth cents per bushel, but in 1913 fifty-five cents is the cost of production, and sixty-six and one-eighth the average return. This means that the cost of production has risen 12.15 per cent., while the price received has fallen nearly 45 per cent. Small wonder under these conditions that the country is being de-populated.

There has been a superstition abroad until quite lately, that somehow Canadian wheat would never fall in price, because of its peculiar nature. Cold-blooded figures, however, tell a different tale, and the Commission puts the quietus on this foolishness with the blunt statement: “There is no best wheat.”

All varieties then come into the market in competition with each other. The farm slave of Western Canada finds himself engaged in cut-throat competition with all other producers, from his next door neighbor to the remotest pioneer on the new prairies of Siberia. Competition has been the slogan of capitalism for many years. It is this competition that is such a powerful lever for exploitation, without it, the masters would not so easily secure the prize.

The value of wheat, then, will not be measured by the amount of labor placed upon a given acre, but by the average total world production. Into this, enters Siberia, Australia, Russia, British India, Argentine, United States of America, Assyria and other minor countries, with their various climatic differences and prices of labor, as for instance, if over ten years in Western farming, six crops of twenty bushels per acre are secured, this means in reality that the same amount of labor has been expended in the production of this one hundred and twenty bushels, as should have produced two hundred bushels. Therefore, it will be readily seen, that given climatic conditions better than those prevailing in this country, such as prevail in British India, the cost of producing the same quantity of wheat is that much less. The effect of these competitors is to be seen in the continued decline in price of Canadian wheat, which the following figures show all too clearly:

1909 . . . . . . . . . .81 1-5th cents per bushel

1910 . . . . . . . . . .76 16th ” “

1911 . . . . . . . . . .74 I-5th ” “

1912 . . . . . . . . . .69 ” “

1913 . . . . . . . . . .66 13th ” “

We have already seen that the amount of labor necessary to produce one bushel of wheat has risen since 1909, due mostly to the pillaging methods of capitalist production, the steady growth of noxious weeds, adverse climatic conditions, and other things which we have not space to deal with in so small a pamphlet. This means in reality that the farmer must slave harder and harder for less and less, and in order to keep pace with the world wide agricultural production, which we have seen has already outdistanced him, must continually procure larger and larger machinery. In other words, that he must bind himself more closely than ever to his master, the capitalist class, and the advice of the Credit Commissions to refrain from procuring these machines, is, we are afraid, either a cynical joke, or a random remark thrown out to cover a hopeless situation, for the commission itself points out that the Saskatchewan farmers are already bound to the machine companies to the tune of Forty Million Dollars, outstanding debt, I913. Six branch offices alone report Fifteen Million, One Hundred and Five Thousand, Seven Hundred and Eighty-six dollars invested in the soil slaves’ hide. Thus it is, the poor farm slave finds himself in a cleft stick, or as you frequently remark, my dear E., “between the devil and the deep sea,” and there are still other factors adding to his misery. The decline in the exchange value of gold plays “ducks and drakes” with what money he does get for his labor, for which the sixty-five cents he now gets will only purchase what forty cents would ten years ago. He must give in the neighbourhood of forty per cent. more gold (labor) for those things he is compelled to purchase, than he did in 1904.

The effect of supply and demand must also be kept in mind. Every farm journal, every experimental station, every would-be-expert urges this poor slave to increase his output. The whole trend of modern industry is directed to this end, for last year, the enormous amount of four billion bushels were poured into the world’s market, and even today sags it down, while this year’s crop is rapidly coming forward.

Added to this is the remarkable fact that the continuous introduction of great machinery to other branches of industry, curtails the number of workers employed, and hence the number of purchasers of farm products, so that chronic overproduction of grain gives prices another downward kick.

LETTER No. 6.

My Dear E., – There is a quaint old book redolent of a peaceful countryside, through whose verdant pages the bleat of young lambs and the tinkle of the cow bells echo: a book well rounded and pleasant to the literary palate, a book well worth reading. Its author, Mish St. John, must have been one of those fine old types we have so often imagined. He calls his book “Letters from an American Farmer.” It made its first appearance in the year of grace, 1782, and gives a splendid view of the peasant proprietor. There is somehow a pleasant smiling fatness about the book; it reeks of the gross prosperity of the small freeholder before the coming of machine industry. Would that our CANADIAN FARM SLAVES might read it, and digest the contents thereof.

Listen for a moment to that rubicund old farmer speaking of HIS SOIL. Is it not that very voice of the past we spoke of in a former letter? :

“The instant I enter upon my own land, the bright ideas of property, of exclusive right, of independence, exalt my mind. Precious soil, I say to myself, by what singular custom of law is it that thou wast made to constitute the riches of the free-holder. What should we American farmers be without the distinct possession of that soil . . . ? This formerly rude soil has been converted by my father into a pleasant farm, and in return it has established all our right. On it is founded our rank, our freedom, our power as citizens, our importance as inhabitants of such a district . . . It is not composed, as in Europe, of great lords who possess everything, and a herd of people who have nothing. Here are no aristocratic families, no courts, no kings, no bishops, no invisible power giving to a few a visible one, no great manufacturers employing thousands, no great refinement of wealth.”

Compare it with this from the United Farmers’ Convention, 1914:

“Whereas the Homesteaders located in those districts who own pre-emptions find it impossible under present conditions to meet the annual payment of interest and principal on same, and Whereas, owing to lack of transportation facilities we have to pay a much higher cost for the necessities of life, and all other materials due to the cost of hauling same. “Be it Therefore Resolved, that this Union of the United Farmers of Alberta urge the Dominion Government through the Minister of Interior to give this matter serious attention, and devise means to relieve the severe hardships suffered by settlers, either by reducing or abolishing payments in cash, and the interest charged, or by allowing extra duties being performed in lieu thereof.”

A painful comparison, I admit, and not altogether to the liking of the booster. You will observe, my dear E., that this old primitive St. John does not pass resolutions about exploitation, but remarks complacently upon the absence of great manufacturers. Ah me! things have changed since then! The destruction of this type of rude happiness, however, is quite in keeping with modern industrial methods, for capitalist production can only reap its full fruit, only blossom in all its sweet flagrance on the grave-mound of free agriculture. Ah! well for old St. John, he heard not the rattle of a roaring freight train, or the ceaseless hum of the giant thresher. Lucky was he, for old St. John could look out into the soft aisles of the surrounding forests, and fear not the coming of the sheriff, and, by the same token, the word mortgage does not seem to have been included in his dictionary. Why! it was not a few years’ ago that farmers were wont to look askance at one of their fellow-farmers who had taken on the burden of a mortgage. It was whispered around the village, behind hands, darkly. He was regarded, as being in the last ditch, driven to bay with his back to the wall. The taking out of such a thing was indeed almost immoral; his right to a seat in the village kirk was even questioned, but we saw, if you recall it, in the last letter, how, despite his most frantic efforts, the farm slave was driven into the all embracing arms of capital, so that today, he looks upon a mortgage in almost a cynical manner. To get a plaster on the farm seems to be all in the day’s work. It is a pity that he has not yet discovered just what this plastering means. It is always presented to him as a benevolent attempt on the part of monied men to help him enlarge his sphere of activity, as the following cutting from a Calgary newspaper gives testimony : –

“One has little conception of the amount of money loaned in Canada each year through its principal loan companies. The important function they play in the progress and prosperity of the people, who are their creditors, is evidenced, etc.,” and you are to understand, my dear E., that this is not by way of a joke, so you will kindly refrain from giggling. However, as a matter of fact, this is but another of those channels through which the average rate of profit on capital invested is procured. Under pressure of the absolutely unremunerative nature of his toil – for who can even live by realizing sixty dollars ($60.00) per hundred bushels of wheat per year? – he is forced to bind himself by that beautiful instrument called a mortgage, tighter, if it were possible, to the capitalist class; is compelled, as it were, to thrust his own unfortunate hide to another sucker of the great octopus.

Out of their own mouths they are condemned, for the Credit Commission again points out that “the present system of payment seemed designed to render renewal necessary and debt perpetual. . .” “The mortgage is not only renewed, but the amount of the loan is very frequently increased.” It is a document that places the farmer from the beginning in an impossible situation; it holds out to him the prospect of confronting a payment he can never hope to meet.

Pressed by that forty million dollars we spoke of before, hounded by collection agents, the poor slave is ready to turn anywhere, and again the Commission points out that mortgage loans are granted: ” (1) to consolidate past debt; (2) for machinery; (3) to provide working capital; (4) to build barns and houses ; (5) to finance trips East.”

It is indeed wonderful that the farmer should imagine the machinery, houses, horses, land, should be other than the property of those who have put up the money to procure them.

Much the same conditions prevail in Alberta, for a Calgary newspaper points out that “Alberta leads all Canada in mortgage loans,” and with blatant cynicism, trumpets it forth as though it were a thing to be proud of, as it is indeed, after all. The masters of this country must indeed feel proud of their ability to bull-doze and exploit the “free and independent farmer of the West,” for surely no other bunch of slaves are so easily robbed. When we consider that in the year 1912 alone, one hundred and thirty-two million, five hundred and twenty-six thousand, and ninety-six dollars, were invested in Canadian real estate, for which the greater portion is farm land, and that and forty-two thousand, one hundred and sixty-five dollars, was and forty-two thousand one hundred and sixty-five dollars, was the amount with which the producers of the country were burdened; when we call to mind the terrible fact that “a conservative estimate would place the amount due to mortgage companies in Saskatchewan, in the neighborhood of sixty-five million dollars,” and further that “while the percentages of increase in Saskatchewan is only a 34.8 per cent., it will be observed that this is considerably less than the percentages of increase pertaining in Alberta”; when we remember that there are forty million dollars outstanding for machinery in Saskatchewan, and “that the farmers of Saskatchewan are paying interest on one hundred and fifty million dollars which costs them twelve million dollars annually” ; and again, “that the average debt is fifteen hundred dollars per farmer,” can there be any doubt but that the title of this pamphlet is justified, and that the whole of the West is but one giant factory, whose roof tree is all out-doors? Is it not remarkable that the ideas of M. St. John still have an abiding place in the minds of some “SLAVES OF THE FARM,” and would it not be equally strange were not many turning to Socialism for relief, as indeed we know they are, my dear E. ?

There is still, however, the professional apologist, who will rush into the breach with master class political economy, exclaiming: “But mortgages are placed upon land, not upon people,” to which the retort is obvious. Will any company advance mortgages on uninhabited land. Were there any mortgages in the West before the country was settled? Nay! So sure are the mortgage companies that the plaster IS on the slave, that if he fails to come through with the interest and principal, he loses his farm, or in plain English, they fire him off and look around for another victim.

The Socialist’s position is unassailable. There can be no value without labor, no interest, no rent, no profit, for all these are but the same thing – unpaid labor. The sweat and skill of thousands of slaves, living as we see them in the West, on the verge of destitution, while the capitalist class fatten upon them, revelling in luxury and ease.

Rent, interest and profit, spell for the “SLAVE OF THE FARM” robbery, insolvency, and pillage, with which unholy trinity, freedom and happiness are total strangers.

LETTER No. 7.

My Dear E., –

We are rapidly approaching the end of these letters. Much has been left unsaid; too little dealt with. The space at my disposal is small, and these short epistles must suffice for the time being. Volumes could be written, chapters filled with figures and statistics, pages with tales of suffering, – to what end?

We have seen that oppression is rife in the West, and that far from being the land of a free people, it is nothing but a continent filled with slaves who labor without ceasing for masters they have never seen, and who care nothing for their welfare

Now, it is axiomatic that oppression brings resistance, and gives rise to organization amongst the oppressed. Instinctively they herd together for mutual protection in obedience to the deep seated idea that in “union there is strength.” However, a working class organization can only have strength in proportion to the amount of real CLASS knowledge existent amongst its members. If those, who go to make up the rank and file of Trade Unions, Farm Organizations and Fraternal Societies, do not understand their position as slaves and workers, as work animals to be fooled, ruled and robbed, that organization is doomed to become a menace to working class interests, and a club wielded by the masters to cow the workers into obedience. For instance, my dear E., how many Orangemen amongst those who go to make up the rank and file have any real knowledge of its sinister mission. How many poor farm slaves, marching proudly on the glorious “twelfth” have the faintest notion that the great order to which they are glad to subscribe, is in reality one of the most powerful weapons of that very “special privilege” and “money power” they are always howling against. How many, think you, see that one organization is used against the other with skill and crafty cunning by those very masters whom the farm slave detests so much ?

Furthermore, the Capitalist Class dread the spread of knowledge upon certain subjects, and organizations that exist to propagate the very precious thing, are hated and feared by them. They will encourage and finance the chloroform associations, and strive to suppress the education of the slaves. Hence, my dear E., we have no reason to suspect the Canadian Government of helping in any way, shape or form, the SOCIALIST PARTY OF CANADA. No subsidy will come our way, they will build no “co-operative” elevators for us or send professors to lecture us on the benefits of organization. They know that we know the skin game in all its ramifications, and, in consequence, save themselves the trouble of offering us what has been aptly described as “sucker bait.” They know that all our time is devoted to spreading amongst the workers, knowledge, which means the finish of exploitation. They are also keenly alive to the failure of their methods, once the slave has opened his eyes.