The socialist case is that oppression, no matter how varied and diverse these might be, can be traced back to a common cause – capitalism. Many of the festering social sores of modern times such as sexism and racism are fostered by the capitalist system. Doctors have known for a long time that the majority of the illnesses and diseases they encounter arise, spread and are exacerbated due to the conditions of poverty their patients live in – and the reason there is poverty – capitalism. In 1934 Einstein wrote in ‘The world as I see it’:

“Nationalism is an infantile sickness. It is the measles of the human race.”

We reject nationalism as anti-working class because it has always tied the working people to its class enemy and divided it amongst itself: the workers have no country. Nationalism is the ideology of an actual or an aspiring capitalist class. The local capitalists are striving to carve out a place for themselves within the existing system, not to overthrow it. Consciously or not, and there are numerous examples of a conscious strategy, capitalism creates and most nation-states emerged after capitalism. A key feature of global capitalism is that the world is organised into a system of states. Israel was founded in a national struggle against the British Empire and resulted in the forced removal of Palestinians and the occupation of the region. Indonesia does not remotely correspond to any pre-colonial domain and possesses an enormous variety of peoples, cultures, languages and religions. The people at one end have far more in common with their neighbours across the national frontier than with their fellow “Indonesians”, its shape was determined by the last Dutch conquests. We witnessed the result of “Indonesian” nationalism in its invasion of West Papua and East Timor.

Nationalism is the ideological justification of the nation-state. It imagines that capitalists and the working class share a common political interest; it imagines that the oppressed and their oppressors, the exploited and their exploiters share a common political interest just because they share the same nationality! It advocates the strengthening or the creation of a nation-state to protect this common interest. The fact that so many different peoples and ethnic groups around the world are oppressed can also be blamed upon capitalism and again only a change to a socialist society offers a permanent cure. Yet according to the wisdom of many left nationalists who argue that these peoples should first gain independence by nation-building and then only afterwards seek socialism. This advice is offered despite the glaring precedents of the history of its actual failure. Of all the national liberation movements of the 1950s to 1980s where has the prospects for socialism advanced? Rather it has been retarded. The strategy that socialists should promote independence ahead of advocating socialism is flawed. Wherever that tactic has been implemented, following independence, socialist influence has faded while the nationalists’ fortunes have prospered.

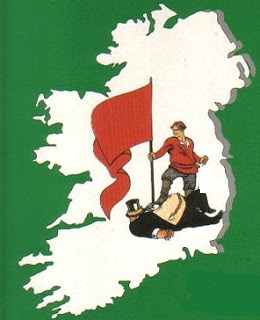

James Connolly, who gave his own life for Irish independence.

Connolly’s example as a prominent left nationalist exposes the fatal fallacy which insists upon placing priority on independence first then afterwards will argue for socialism. History reveals when they do, it is socialism that is subsequently forgotten. We only need to look back at the fate of the Irish socialists who followed Connolly despite his own earlier scepticism at the wisdom of such a tactic. The Citizens Army formed to fight the pro-nationalist employer Murphy during the Dublin lock-out ended up disappearing into the ranks of the pro-employer nationalist movement. Despite the sacrifice of their lives, Irish socialism did not emerge any the stronger. Irish nationalism was hostile to the cause of labour.

The reasons for Connolly’s decision to embark on an uprising in collaboration with the Irish Republican Brotherhood is up for conjecture and speculation. Perhaps, as some suggest, it was his disillusionment with the capitulation to jingoism of all the various 2nd International political parties when war broke out. But what we do know is that it went against his own previous cautionary warnings of doing such a thing. Connolly repeatedly insisted upon political action by the working class independent of the capitalist class and had written that any alliance with the employers would be class treachery. It was sadly the same accusation that the play-wright and Citizen Army veteran Sean O’Casey who concluded that “Jim Connolly had stepped from the narrow byway of Irish Socialism onto the broad and crowded highway of Irish Nationalism”. O’Casey wrote in his History of the Irish Citizens Army “Liberty Hall was no longer the Headquarters of the Irish Labour movement, but the centre of Irish national disaffection.” Like most socialist leaders, Connolly surrendered to patriotism in 1914 but in his case, it was Irish patriotism. He signed the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, a document with little socialist content.

How tragic it is that Connolly did not heed his early warnings:

“Nationalism without Socialism – without a reorganisation of society on the basis of a broader and more developed form of that common property which underlay the social structure of Ancient Erin – is only national recreancy.

It would be tantamount to a public declaration that our oppressors had so far succeeded in inoculating us with their perverted conceptions of justice and morality that we had finally decided to accept those conceptions as our own, and no longer needed an alien army to force them upon us.

As a Socialist I am prepared to do all one man can do to achieve for our motherland her rightful heritage – independence; but if you ask me to abate one jot or tittle of the claims of social justice, in order to conciliate the privileged classes, then I must decline.

Such action would be neither honourable nor feasible. Let us never forget that he never reaches Heaven who marches thither in the company of the Devil. Let us openly proclaim our faith: the logic of events is with us.”

The 1913 Dublin Lock-out was initiated by William Martin Murphy, who was a former Irish nationalist MP, who had actually refused a knighthood on the grounds that Home Rule was denied to Ireland. During the lock-out, there were frequent vicious police attacks on strikers resulting in James Nolan and James Byrne being clubbed to death. The funeral of James Nolan attracted over 30,000 people and was guarded by I.T.G.W.U. men with pick-handles against police attack who chose wisely keep their distance. It was against this background that the idea of a citizens army took root in peoples minds. At the end of October Larkin announced that he was organising a citizens army to defend the workers. On November 13th, Connolly announced that a citizens army was to be organised along military lines by Captain Jack White . The very fact that they had rudimentary weapons such as hurley sticks etc, and were fully prepared to use them, to quote Jack White, “put manners on the police”. The very existence of the ICA subdued the police.

Other nationalists, such as Arthur Griffith, the Sinn Fein leader, supported Murphy and the employers during the lockout and venomously criticised the strikers, especially Jim Larkin, referring to Larkin as “the English trade unionist” who was trying to destroy Irish industry to the advantage of British industry. The Sinn Fein paper, ‘Irish Freedom’ wrote;

“We have seen with anger in our hearts and the flush of shame on our cheeks English alms dumped on the quays of Dublin; we have had to listen to the lying and hypocritical English press as it shouted the news of the starving and begging Irish to the ends of the earth; we have heard Englishmen bellowing on the streets of Dublin the lie that we are the sisters and brothers of the English.. and greatest shame of all, we have seen and heard Irishmen give their approval to all these insults.. God grant that such things may never happen in our land again.”

The Citizen Army’s first handbill contained a list of reasons not to join the IRB Volunteers, (controlled by forces opposed to labour, officials having locked out union men ..,) and a list of reasons to join the Citizen Army (controlled by working-class people, refuses membership to people opposed to labour..,). In his autobiography, O’Casey reminds us that the Irish Volunteers were “streaked with employers who had openly tried to starve the women and children of the workers, followed meekly by scabs and blacklegs from the lower elements among the workers themselves, and many of them saw in this agitation a plumrose path to good jobs, now held in Ireland by the younger sons of the English well-to-do.”

Connolly had good reason to despise the nationalists and in numerous articles, he explained it very clearly. He laid out the Marxist internationalist case for workers emancipation, exposing the shortcomings of the Irish nationalist movement as a path for working-class liberation. He mocks their romantic calls of “freedom” and instead calls for unity, not as a nation, but as a class. He calls not for the independence of the Irish capitalist class, but for the working class. Workers have no country, but one struggle. Connolly’s words ring as true today as it did then.

He wrote in The Workers’ Republic, 1899:

“Let us free Ireland! Never mind such base, carnal thoughts as concern work and wages, healthy homes, or lives unclouded by poverty.

Let us free Ireland! The rack renting landlord; is he not also an Irishman, and wherefore should we hate him? Nay, let us not speak harshly of our brother – yea, even when he raises our rent.

Let us free Ireland! The profit-grinding capitalist, who robs us of three-fourths of the fruits of our labour, who sucks the very marrow of our bones when we are young, and then throws us out in the street, like a worn-out tool when we are grown prematurely old in his service, is he not an Irishman, and mayhap a patriot, and wherefore should we think harshly of him?

Let us free Ireland! “The land that bred and bore us.” And the landlord who makes us pay for permission to live upon it. Whoop it up for liberty!

“Let us free Ireland,” says the patriot who won’t touch Socialism. Let us all join together and cr-r-rush the br-r-rutal Saxon. Let us all join together, says he, all classes and creeds. And, says the town worker, after we have crushed the Saxon and freed Ireland, what will we do? Oh, then you can go back to your slums, same as before. Whoop it up for liberty!

And, says the agricultural workers, after we have freed Ireland, what then? Oh, then you can go scraping around for the landlord’s rent or the money-lenders’ interest same as before. Whoop it up for liberty!

After Ireland is free, says the patriot who won’t touch socialism, we will protect all classes, and if you won’t pay your rent you will be evicted same as now. But the evicting party, under command of the sheriff, will wear green uniforms and the Harp without the Crown, and the warrant turning you out on the roadside will be stamped with the arms of the Irish Republic. Now, isn’t that worth fighting for?

And when you cannot find employment, and, giving up the struggle of life in despair, enter the poorhouse, the band of the nearest regiment of the Irish army will escort you to the poorhouse door to the tune of St. Patrick’s Day. Oh! It will be nice to live in those days!

“With the Green Flag floating o’er us” and an ever-increasing army of unemployed workers walking about under the Green Flag, wishing they had something to eat. Same as now! Whoop it up for liberty!

Now, my friend, I also am Irish, but I’m a bit more logical. The capitalist, I say, is a parasite on industry; as useless in the present stage of our industrial development as any other parasite in the animal or vegetable world is to the life of the animal or vegetable upon which it feeds.

The working class is the victim of this parasite – this human leech, and it is the duty and interest of the working class to use every means in its power to oust this parasite class from the position which enables it to thus prey upon the vitals of labour.

Therefore, I say, let us organise as a class to meet our masters and destroy their mastership; organise to drive them from their hold upon public life through their political power; organise to wrench from their robber clutch the land and workshops on and in which they enslave us; organise to cleanse our social life from the stain of social cannibalism, from the preying of man upon his fellow man.

Organise for a full, free and happy life FOR ALL OR FOR NONE.”

This was no isolated occasion that Connolly was scathing of his future comrades-in-arms-to-be:

“If you remove the English army to-morrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain.

England would still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and the blood of our martyrs. England would still rule you to your ruin, even while your lips offered hypocritical homage at the shrine of that Freedom whose cause you had betrayed.”

Again he repeats his declaration of the independence of the working class but one in the end he himself failed to up-keep:

“On the working class of Ireland, therefore, devolves the task of conquering political representation for their class as the preliminary step towards the conquest of political power. This task can only he safely entered upon by men and women who recognise that the first action of a revolutionary army must harmonise in principle with those likely to be its last, and that, therefore, no revolutionists can safely invite the co-operation of men or classes, whose ideals are not theirs, and whom, therefore, they may be compelled to fight at some future critical stage of the journey to freedom. To this category belongs every section of the propertied class, and every individual of those classes who believes in the righteousness of his class position.”

Connolly was indeed a paradox. He went beyond the parochial and embraced the cosmopolitan culture. An example of his internationalism is Connolly’s attachment to the international language of Esperanto.

In Workers’ Republic of December 2nd 1899, Connolly wrote:

“I believe the establishment of a universal language to facilitate communication between the peoples is highly to be desired. But I incline also to the belief that this desirable result would be attained sooner as the result of a free agreement which would accept one language to be taught in all primary schools, in addition to the national language, than by the attempt to crush out the existing national vehicles of expression. The complete success of the attempts at Russification or Germanisation, or kindred efforts to destroy the language of a people would, in my opinion, only create greater barriers to the acceptance of a universal language. Each conquering race, lusting after universal domination, would be bitterly intolerant of the language of every rival, and therefore more disinclined to accept a common medium than would a number of small races, with whom the desire to facilitate commercial and literary intercourse with the world, would take the place of lust of domination.”

Connolly agreed with one of the central arguments for Esperanto, namely that the language problem will never be solved by one of the great powers trying to impose its language on the others. Esperanto can be acceptable to all because it gives no nation a special advantage.

Some years later in The Harp (April 1908) he wrote:

“I do believe in the necessity, and indeed in the inevitability of an universal language; but I do not believe it will be brought about, or even hastened, by smaller races or nations consenting to the extinction of their language. Such a course of action, or rather of slavish inaction, would not hasten the day of a universal language, but would rather lead to the intensification of the struggle for mastery between the languages of the greater powers.

On the other hand, a large number of small communities, speaking different tongues, are more likely to agree upon a common language as a common means of communication than a small number of great empires, each jealous of its own power and seeking its own supremacy.”

When he stood in a municipal election in Dublin in 1902, Connolly issued an election leaflet in Yiddish and again it emphasises his disdain for the Irish nationalist:

“No, you cannot vote for the Home Ruler, the candidate of the bourgeoisie! The Home Rulers speak out against the English capitalists and the English landlords because they want to seize their places so that they themselves can oppress and exploit the people. No mater how nicely and well the Home Rulers talk or how much as friends of man they seek to appear or how much they shout about oppressed Ireland – they are capitalists. In their own homes they can show their true colours and cast off their revolutionary democratic disguise and torment and choke the poor as much as they can. And you, Jews, what assurance do you have that one fine day they will not turn on you?

You ought to vote for the Socialist candidate and only for the Socialist candidate. The Socialists are the only ones who stand always and everywhere against every national oppression.”

In contrast to these socialist attitudes, after war broke out, Connolly increasingly abandoned socialism for nationalism which can be seen in his article “The Slackers”, published in the Workers’ Republic on 11 March 1916, which attacks Scots and English workers who had come to Ireland to escape conscription. Those “curs” and “Brit Huns” were attacked for cowardice and for stealing jobs from Irishmen. A reply from Glasgow reader suggested that the workers Connolly attacked had moved to Ireland, where many of their parents came from, to avoid being called up and were behaving sensibly and properly. Connolly’s response made it clear that the “curs” were guilty whether they fought in the army or worked in Scotland, England or Ireland. His attitude may well come from those who would deny asylum seekers refuge.

His support for German imperialism is expressed in an article, “Forces of Civilisation” in Workers’ Republic where he describes “The German Empire is a homogeneous Empire of self-governing peoples; the British Empire is a heterogeneous collection in which a very small number of self-governing communities connive at the subjugation, by force, of a vast number of despotically ruled subject populations. We do not wish to be ruled by either empire, but we certainly believe that the first named contains in germ more of the possibilities of freedom and civilisation than the latter”. This apology referring to a nation that committed genocide in South West Africa against the indigenous Hetero people. His seeming apologies for the German Empire appears to be a far cry from when he wrote

“And don’t make the mistake of lauding the Kaiser, either, as our so-called nationalist journals do. He has always proven himself to be a most determined enemy of the working class, and longs for the day when he may drown in blood their hopes for freedom..He is your enemy, as the English governing class is your enemy, as the Irish propertied class is your enemy, as all the classes who live upon your labour in all the nations of the world are your enemy.”

The “Free” State

And just what did the blood sacrifice as some describe it produce? We can speculate on Connolly role if he had survived and perhaps offer the example of Countess Markiewicz, who became Minister of Labour in the first republican government and died a firm supporter of De Valera. He certainly would have been an asset to Ireland’s new rulers in their task of getting the labour movement to subordinate its own interests to the task of national construction, as in the case of the numerous ANC militants in South Africa. Another signal of co-option was the number of left republican protestants and widows of republicans who converted to catholicism in after 1916. These included Constance Markievicz, Lillie Connolly, the widow of James Connolly. Catholicism had become the religion of Irish nationalism. Perhaps Connolly too would have returned to the bosom of Mother Church as there may be good grounds to believe he did on his death-bed. Such speculation is however pointless though because Connolly’s stature is due to his death and martyrdom. The Citizen’s Army fades from history just when a vital need for an independent armed force on behalf of the workers was soon to be only too apparent.

After independence working people had high hopes but over the following decade, they were harshly suppressed by the new Irish government. Ireland’s new political elite would effectively turn the clock back and enforce the status quo that had existed in Ireland years if not decades before the War of Independence. Ireland’s first post-independence government successfully suppressed political opposition and the workers’ movement and went on to enforce their moral and ethical values on wider society, ably supported by the conservative invidious influence of the Catholic Church and the consequences are surfacing even today with the tales of the Magadalene Laundries and illegitimate children of the poor left to die and discarded in cess-pits.

In December 1922 four prominent republicans, Liam Mellows (IRA quartermaster), Joe McKelvey (former IRA Chief of Staff) , Rory O’Connor (IRA Director of Engineering) and Dick Barrett were executed. Thomas Johnson the labour leader vented his fury over the executions and said “I am almost forced to say you have killed the new State at its birth” but he missed the point. They had not killed the state, quite the opposite. It was the bloody after-birth of a State being born. The Free State were well aware of what they were doing. The repression strengthened and secured the power of the native Irish capitalist class who would successfully lay down the groundwork for a deeply authoritarian state that they would use to break all opposition regardless of its nature. Although the president of the administration was William Cosgrave, the Cumann na nGaedheal government was increasingly under the influence of Kevin O’Higgins who famously quipped that Cumann na nGaedheal were the “most conservative-minded revolutionaries that ever put through a successful revolution”.

It was a scenario foreseen by Connolly:

“Having learned from history that all bourgeois movements end in compromise, that the bourgeois revolutionists of today become the conservatives of tomorrow, the Irish Socialists refuse to deny or to lose their identity with those who only half understand the problem of liberty. They seek only the alliance and the friendship of those hearts who, loving liberty for its own sake, are not afraid to follow its banner when it is uplifted by the hands of the working class who have most need of it. Their friends are those who would not hesitate to follow that standard of liberty, to consecrate their lives in its service even should it lead to the terrible arbitration of the sword.”

The Free State government having won its civil war then uses its military to crush the workers’ movements. Labour historian Emmet O’ Connor describes how thousands of paramilitary police (Special Infantry Corps) were deployed so that by the Spring of 1923 “military intervention was becoming a routine response to factory seizures or the disruption of essential services”. During the Waterford farm strike of 1923 “600 SIC were billeted in a chain of posts throughout the affected area.”

In September 1922, 10,000 postal workers went on strike provoked by a government which rejected the findings of its own commission of enquiry into the cost of living for postal employees and imposed a wage cut. The reaction of the government was all too predictable and the army was sent in to break the strike, soldiers threatening strikers and armoured cars driven into picket lines. “Numerous arrests and re-arrests of pickets were made until the right to peacefully picket was asserted in the courts. Even then, troops continued to intimidate strikers with armoured vehicles and rifle fire. On 17 September a lady telephonist was shot in the knees. Raids took place on union offices and arrests of officials continued.” O’Connor writes. This was to demonstrate to the workers that ‘law and order’ had been restored.

The rural poor were also victims of Cumann na nGaedhael in power. Hoping to cultivate a support base with larger farmers in Ireland, they supported these farmers in their ongoing attempts to drive down the wages of landless agricultural labourers. These labourers formed around 23% of the rural workforce. As a class, they had been the big losers during the land war of the 1880′s as they could not benefit from reforms that allowed farmers buy land given they had none. Their attempts to gain a stake in Irish rural society through organising themselves in the ITGWU (The Irish Transport and General Workers Union) in the early 20th century was fiercely resisted by farmers. In 1923 farmers, emboldened by the knowledge that the Free State would support them, locked out thousands of unionised labourers in attempts to drive down wages. In Athy, Co. Kildare when farmers locked out 350 labourers the National Army arrested the ITGWU branch secretary in the area. When a farmer was attacked and a threshing machine damaged 8 trade unionists were arrested and held for 3 months without trial or charge.

Over 400 landlords were dispossessed by agricultural labourers (often ITGWU members). This went on until the IRA came to the aid of the gentry by having the republican land courts order an end to “illegal seizures”. This was not an isolated incident. The IRA was increasingly moving against workers’ struggles. Among the better-known examples are the smashing of a farm workers’ strike at Bulgaden and the eviction of a ‘Soviet’ occupation from the mills at Quarterstown. Though they didn’t always get their own way, one case was at Kilmacthomas when the IRA tried to keep the roads open while strikers were stopping the movement of scab labour and goods.

Later in the year when 1500 labourers were locked out in Waterford the response was similar. The state sent in 600 Soldiers and the entire of East Waterford was put under a curfew between 11p.m. and 5:30 am. Meanwhile, nothing was done to stop vigilantes organised by farmers called “White Guards” attacking union organisers across the county. The land-owners, backed by the state, emerged victorious and crushed the union.

This, accompanied by high unemployment, broke the power of organised rural labour. The ITGWU’s membership halved in the following three years. This was reflected by the fact that within 5 years days lost to strike action were reduced by 95%. In the absence of unions, the government clearly had no interest in their welfare and the labourers had no one to defend their corner. This saw their living standards plummet. There was a 10% fall in agricultural labourers’ wages between 1922 and 1926 and a further 10% in the following 5 years. These policies saw a whole section of the rural population – the labourers – disappear through emigration, little wonder gave their income had fallen by 20% between 1923 and 31.

The desperate living standards of the urban poor was one of the greatest single social issues facing “The Free State” in 1923. The tenement population in Dublin lived in crushing poverty. However, instead of helping the poorest of the poor, the government focused on building houses for the well-off, which saw the expansion of the suburbs on the fringes of Dublin. Little was done to alleviate the conditions among the urban poor in Dublin. Housing construction was largely privatised and thus little was done to alleviate the desperate squalor in which people lived as they could never afford housing. Dublin Corporation only built an average of 483 houses a year between 1923 and 1933. This led to the deterioration of housing conditions. In 1926, when a census was conducted, over a third of the population of Dublin lived in housing conditions with an average of 4 people per room. This disregard for overcrowding was worsened by their tax approach. Appealing to the rich in society the Free State, short of money, reduced income tax from what was 27% to 15% and instead turned to indirect taxation, which had a greater impact on the poor. The outcome of these policies was revealed in 1926 when the statistic of an infant mortality rate of 12% among children younger than one in urban areas was revealed. The indifferent attitude of Free State politicians would allow this to continue unaddressed with all its devastating consequences.

James Connolly tried to stand with a foot in both the socialist and nationalist camps simultaneously. Like the left nationalists of today, he hoped that the bulk of nationalist supporters would learn in the course of the independence struggle to throw in their lot with the socialist movement. Unfortunately, that was not to be, for the siren call of the national patriot proved stronger than the appeal to class solidarity.

Connolly joined forces with a class enemy who would welcome the outbreak of world war by saying:

“The last 15 months have been the most glorious in the history of Europe. Heroism has come back to the earth. It is good for the world that such things should be done. The old heart of the earth needed to be warmed with the red wine of the battlefields. Such august honour was never offered to God as this.”

Or wallow in the death-wish by writing:

“I know that Ireland will not be happy again until she recollects that laughing gesture of a young man that is going into battle or climbing to a gibbet.”

James Connolly, rather than maintain the independence of the labour movement and stay true the socialist goal, chose to go in alliance with the likes of Patrick Pearse who could write in The Coming Revolution:

“We might make mistakes in the beginning and shoot the wrong people but bloodshed is a cleansing and sanctifying thing.”

Which was a policy that very much resembled the practices of the new independent government, representatives of Ireland’s ruling class and, as such, the very people who had led Connolly to conclude the necessity of establishing the workers’ militia, the Irish Citizen Army. The same old nationalist leadership had no problem declaring that their idea of freedom did not include freedom from the employers whose interests they serve.