The aim of this article is to explore the effects of a particular form of technology on the state of society. It will examine the concepts of robotics and artificial intelligence; the concept of the technological singularity; what such an event would mean for the labour market; and, because of the central role of the labour market to capitalism, what this would mean for capitalist society as a whole. It will also take in the contradictions in capitalisms need for labour; and how, ultimately, socialism is essentially the emancipation of labour.

Near future science fiction frequently explores the possibilities of imminent technologies. Gadgets that haven’t been designed yet, but could be given recent real advances in technology and design. Whilst its track record on such predictions as us getting to Mars by 1977 and everyone having rocket cars by 2002 are a bit wide of the mark, others have been much closer – and in fact actively conservative compared to the real historical record.

Authors such as Charles Stross in his Halting State or Ken Macleod in his Night Sessions explore a future where mobile phone technology linked up to glasses which display information to the wearer can link up with technology like google Earth and GPS systems to tell them, just by looking, who lives in a house and what criminal records they have and other known details. They explore the expanding pace of technology, as the machine intelligence of computers begins to exceed that of the living human beings. Iain M. Banks in his Culture novels explores the after effects of that process, where humans served by loyal robots live in a post scarcity anarcho communist space faring society.

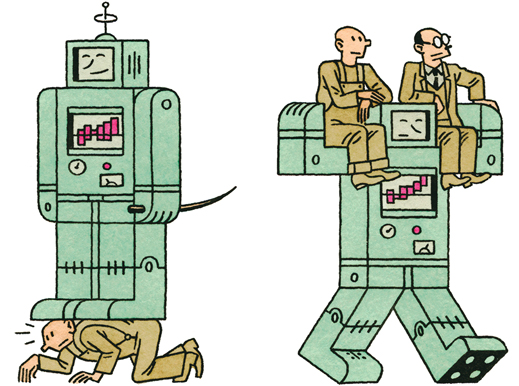

We need to pause here to discuss some terms. Much of this will be familiar. The difference, for one, between a machine and a tool. A tool enables a human to do a job, while a machine effectively replaces human labour. A robot is a sort of machine. The word itself is Czech, coming from a play about automatons, and it means worker, but with connotations of slavery. The international standards organisation defines a robot as: “an automatically controlled, reprogrammable, multipurpose, manipulator programmable in three or more axes, which may be either fixed in place or mobile for use in industrial automation applications.” Which more or less means the same thing.

Robots do not have to be physical, and many expert systems can be described as a robot of sorts. When your word-processor corrects your spelling, that is a type of robot.

A singularity represents an “event horizon” in the predictability of human technological development past which present models of the future cease to give reliable or accurate answers, following the creation of strong artificial intelligence or the amplification of human intelligence. Futurists predict that after the Singularity, humans as they exist presently will cease to be the dominating force in scientific and technological progress, replaced with posthumans, strong AI, or both, and therefore all models of change based on past trends in human behavior will be obsolete.

The technological singularity refers to a situation in which technological advancement begins to accelerate to the point where new designs are produced, basically, before old ones are implemented: where super intelligence exists. More prosaically, when the robots begin to be able to do our thinking for us. Proponents of such an eventuality point to growth of computer processing power and the growth of communications and transport technology. The mark how the time taken for products to reach ubiquity and obsolesence is falling – it took 70 years for telephones to become ubiquitous, the iPod has managed it in about 8. For example.

We’ve even reported such trends ourselves, in the Socialist Standard. We told how 3D printers have been developed that can make models and parts out of sillicon and plastic – and how that will lead to faster development of prototypes. Those 3D printers can also produce 60% of their own parts. If they get to 100% we’d have multipurpose machines that could reproduce themselves, and maybe even adapt for different tasks.

Machines making machines. This would have drastic effects on the labour market. Robin Hanson writes in the IEEE Spectrum:

The relative advantages of humans and machines vary from one task to the next. Imagine a chart resembling a topographic cross section, with the tasks that are ”most human” forming a human advantage curve on the higher ground. Here you find chores best done by humans, like gourmet cooking or elite hairdressing. Then there is a ”shore” consisting of tasks that humans and machines are equally able to perform and, beyond them an ”ocean” of tasks best done by machines. When machines get cheaper or smarter or both, the water level rises, as it were, and the shore moves inland.

Depending on how these contours actually lie, this could mean mass displacement for millions of workers: redundancy on a grand scale. From shop staff to clerks, essentially human posts could be done away with by “simple” intelligences or machine expertise.

Of course, this trend has been continuing since capitalism began. As Hanson notes:

The […] proliferation of machine-assembled cars raised the value of related human tasks, such as designing those cars, because the financial stakes were now much higher. Sure enough, automobiles raised the wages of machinists and designers

Throughout history, the labour market has had winners and losers, swings as well as roundabouts. New workers have always been recruited to replace those throw on the scrapheap; but in this scenario, new workers can be designed, trained up and introduced faster through machinery that it would take to breed and train a new generation of humans.

The suggestion throughout discussion of a technological singularity is that productivity would soar. In essence, it would herald an abundance economy. For some radical “trans humanists” this would mean the end of capitalism.

The capitalist mode of production carries with it a strong impulse for this sort of increasing :

The battle of competition is fought by cheapening of commodities. The cheapness of commodities demands, caeteris paribus, on the productiveness of labour, and this again on the scale of production. Therefore, the larger capitals beat the smaller. It will further be remembered that, with the development of the capitalist mode of production, there is an increase in the minimum amount of individual capital necessary to carry on a business under its normal conditions. The smaller capitals, therefore, crowd into spheres of production which Modern Industry has only sporadically or incompletely got hold of. Here competition rages in direct proportion to the number, and in inverse proportion to the magnitudes, of the antagonistic capitals. It always ends in the ruin of many small capitalists, whose capitals partly pass into the hands of their conquerors, partly vanish.

The result of which is the fact that:

…the growing extent of the means of production, as compared with the labour-power incorporated with them, is an expression of the growing productiveness of labour. The increase of the latter appears, therefore, in the diminution of the mass of labour in proportion to the mass of means of production moved by it, or in the diminution of the subjective factor of the labour-process as compared with the objective factor.

The additional capitals formed in the normal course of accumulation serve particularly as vehicles for the exploitation of new inventions and discoveries, and industrial improvements in general. But in time the old capital also reaches the moment of renewal from top to toe, when it sheds its skin and is reborn like the others in a perfected technical form, in which a smaller quantity of labour will suffice to set in motion a larger quantity of machinery and raw materials. (Marx, Capital vol 1, Chapter 25)

While 90% of what socialists discuss, from inequality to exploitation and unemployment, can be defended without needing recourse to the labour theory of value, (and some writers have suggested Marx should be dealt with in this way) not doing so robs our theories of their explicitly political dimension. As can be seen from the preceeding, the capitalist mode of production is as much about drawing in the command of labouring humans as it is about making profits – it is a source of social control.

Capitalism is in a bind – it wants to use as much labour as it can as little as possible. That is, while it on the one hand sets its production goals as limitless, an infinity of riches and products, it wants to spare the precious labour that gives it an edge in the competitive battle. This is what the shackles of capital mean to labour, that goals and activities that are within the practical bounds of human endeavour are left insurmountable because it is not capitalistically efficient to do so. Capitalism prefers the increasing refinement of the productive process to the actual attainment of any specific outcomes or goods.

This brings us to an important factor. As EP Thompson noted in his The Making of the English Working Class – the working class made themselves. Workers, and their demands for waged labour as compared with the previous forms of bonded labour, were, if you’ll forgive, in the vanguard of promoting market relations. Professor Robert Allen of Nuffield College, Oxford, an economic historian, goes so far as to suggest that a significant contributing factor to the Industrial Revolution occurring in Britain was the relatively high (at that time and in the world) Real wages of the workers here. Particularly, they were high relative to fuel costs and capital costs. The importance of this is that it incentivised innovation and mechanisation. Similar features have been attributed to American industrialisation. The high costs of labour, and capitalism’s drive to spare labour if at all possible is a key motor of capital accumulation.

This, then, presents us with a bind. Capitalism spares labour, cuts labour and labour costs, while it grows. Further, as we’ve seen above, whilst it accumulates, it cheapens the products of industry. This presents us with a situation in which fewer people are employed, and in which the cost of employing people actually falls. The mass of use values they can command may well increase, but the value of their pay declines. We can see this in the recent history of the United States “Since 1975, practically all the gains in household income have gone to the top 20% of households” – that’s from the CIA world factbook.

This raises the prospect, as the tides of technology rise and surplus population increases and real wages fall, of a natural limit to technological growth – the point at which the labour market ceases incentivise intensive exploitation of capital, and it becomes cheaper to simply exploit labour extensively. The Socialist Party has never emphasised a theory of “decadence” like some Marxist groups, but these conditions would be as close to a decadence situation as you could find. Hanson sees a situation in which we would all have to become capitalists, because labour would not longer pay, but if what I have suggested above comes to pass, then we simply wouldn’t have that option, and a form of labour feudalism could emerge.

In response to a questionnaire, when Marx was asked what were his goals, he simply replied “The emancipation of labour.” This brings us to the crux of the matter – technology emancipates us from labour, but so long as a vast swathe of humanity depends on the sale of its ability to work labour will be in the chains of capital. Socialism, the emancipation of labour, would see a situation in which rather than try at all costs to spare labour, we will freely chuck it at problems because we would be working towards definite ends, rather than an ever increasing size of profit.

It would be nice to think that technological progress would simply evolve capitalism away. If we believed that, we could shut up shop and simply become cheer-leaders for advancing bleeding edge technology. The dangers of the alternative, a kind of stagnant capitalism based on cheap super abundant labour unable to fight back, is quite terrifying. We’ve seen how capitalism does have a drive to advance technology, but one that may be undercut by its dependence on wages labour. Waged labour has not been the passive tool of capital, but an active and essential participant in driving capitalism onwards. I’d suggest that we as workers cannot sit by and hope that a magic bullet will solve our social problems, and our active organisation remains essential to attaining socialism.

Thus, I’d like to finally touch on an old debate we once had at conference – the question was whether socialism was possible in 1904. The arguments tonight may make it sound like it was not so, that we’re still waiting for the robotic productive forces that will make it possible; I would argue, though, that productive forces encompasses more than technological capacity, and includes the organisational and mental capacities required for a given form of society. The friction between capital and labour was a source of technological innovation, that friction was a productive force. As I said just before, socialism will free up labour, irrespective of technological capacity, to use whatever technological powers are available. Socialism is not a by-product of technology but of social consciousness.

Thank you.

Bill Martin

Notes:

http://www.spectrum.ieee.org/robotics/robotics-software/economics-of-the-singularity

http://www.economics.ox.ac.uk/members/robert.allen/Presentations/leyden-2.pdf

http://www.doktorsleepless.com/index.php/Singularity