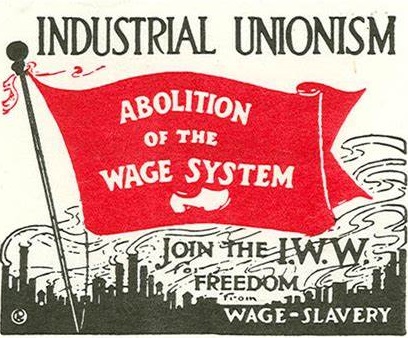

“Instead of the conservative motto, “A fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work!” they ought to inscribe on their banner the revolutionary watchword, “Abolition of the wages system!” (Karl Marx, Value, Price and Profit.)

Though the World Socialist Movement doesn’t necessarily agree with the Industrial Workers of the World on everything, but we do think they present a clear and concise exposition of a central plank of the revolutionary socialist platform: our shared commitment to the abolition of the wages system and the end of wage-slavery.

What does the IWW mean by the “Abolition of the Wages System”?

The Industrial Workers of the World believe in a better life for all. In considering what’s right and what’s wrong with our present society, the I.W.W. naturally includes how we are paid for the work we do: wages and salaries.

What are wages?

Wages or salaries are the money given to us by the boss in return for a set amount of time we spend at the job. We get so much an hour, or so much a month. Whether we’ve spent the day working hard or had to “look busy” much of the time, we receive exactly the same amount.

But for the same eight hours of employment, people are paid greatly varying amounts. We are paid different rates for doing the same job in different locations (i.e., truck assemblers get paid more in Windsor than in Vancouver) and for doing different jobs in the same location (i.e., in Vancouver accountants are paid more than daycare workers). Even when we’re employed by the same company in the same building, various tasks are often paid at varying rates (i.e., electricians, assembly line workers, secretaries).

These differences in pay are mostly a result of events which happened in our past: our history. Certain jobs get a particular rate of pay because of some decisions by the boss. Other jobs get a particular rate of pay because of actions taken by our forefathers and foremothers. As teachers grew more militant. for example, that task changed from a low-paying to a better-paying one. Overall, unionized jobs show the results of past fights for better pay and conditions.

On the other hand, a failure to stay militant results in lower comparative wages There was a time in B.C.’s history when woods workers overall were among the highest-paid blue-collar employees. No longer.

On every job, a number of excuses are offered to explain why I should get more pay than you, and why he or she receive more than both of us combined. Years of education and training are often cited, though this education is largely supported out of taxes we all pay. So those who receive this education really benefit twice. Meanwhile, should employees with four years of university receive more than employees with seven years of an apprenticeship?

Another argument is that some people have more responsibility or take more risks. This can be in connection with our own life or others’ lives, or concerned with valuable items or money. But then, why aren’t those who work at the most hazardous jobs (as determined by Workers’ Compensation Board statistics) the most highly paid? Or. why don’t bank tellers earn a lot of money?

Should the people who produce what society needs most be the best paid? This would mean that farmers and agricultural laborers who produce our food would be among the highest paid people. They aren’t now! And those who manufacture our clothing are still often immigrant women working for very, very low pay in sweat-shop conditions. And the host of non-union carpenters and others building our housing aren’t very well reimbursed for their work, either.

What’s wrong with wages?

As can be seen, then, the present wage system is totally irrational. It is a hodge-podge of differing amounts paid to people for a range of often-contradictory “reasons”. In fact the work of all of us (however humble) is equally necessary to keep this society going.

About the only sure conclusion that can be gathered from the present wage system is that the further up the corporate ladder from actually producing goods or services a person is, the more money he or she takes home.

As well, most of us are really paid only enough to meet our basic needs. Advertising makes sure we consume as much as possible, and the widespread extension of credit makes sure we spend most of our lives in debt.

Besides being irrational, the present wage system is completely undemocratic. We are constantly told by teachers, the media and politicians that we are free citizens of a democracy. But this democracy ends for us the moment we show up for work. On the job we not only do not make the decisions, but we have to obey the orders of people we definitely did not elect to rule over us.

If we don’t like it, we are “free” to quit. After that, we can either “freely” starve to death or “freely” agree to obey the orders of some other employer on some other job.

When we are employed, we get as wages only a part of the value of what we produce. We are therefore robbed at the point of production; this is the true meaning of exploitation. Besides our wages, the product of our labor goes to pay for raw materials, for research and development, for things our community needs (paid for in the form of taxes) and for profits taken by the already rich owners and managers.

It’s true that in any social system workers would not be able to receive as wages the complete value of the product of our labor, for all systems require plant maintenance, research and development, etc. But the decision as to how to divide up among these categories the wealth produced as a result of our work is not made by us.

Until we who produce this wealth can decide ourselves how it will be used, there is no such thing as a “fair” wage or salary for any of us.

Finally, the wage system as a whole defines our society. Who can really determine what we are “worth”? To classify people according to “worth” is undemocratic, anti-human, a vestige of a barbarous past. All human beings have worth by nature of their humanness. It is only a step from classifying people according to “worth” to deciding to exterminate the “unworthy”. The roots of the Russian Gulag and the German gas chamber lie within the wage system.

In our society today, we pretend there are paying jobs for all who “want to work” and those who have such jobs enjoy the best things of life. The rest of society – housewives, the unemployed, senior citizens and so on – has to settle for a lower standard of living and/or being dependent on the personal goodwill of those who are presently employed.

No one has ever proven that our society can provide a constantly-growing number of jobs to match population growth and displacement by technology. Indeed, the evidence is that society can’t. But under the wage system, society is still organized to offer rewards and punishments, praise and blame, as though these wage-paying jobs are available for all.

What would replace the wage system?

The present irrational, undemocratic wage system has to go. What the I.W.W. offers in its stead is not a blueprint, but an opportunity. We believe a reorganization of society is needed so that decision-making on the job as well as off is made democratically.

Since human beings are remarkably ingenious, we believe different groups of people will come up with different democratic alternatives to the present way of running society.

Wouldn’t this be a happier place to live if the available work and resources were more equally shared than at present?

Shouldn’t we put an end to the traffic in human flesh – where we have to compete with others just like ourselves as we sell our talents and time and selves to the highest bidder in order to get a means of livelihood?

How much of what we do at our job is really necessary, helpful, ecologically beneficial, moral?

How can there be world-wide unemployment on a planet where much of the population is starving, ill-housed, ill-clothed, illiterate? Why is the world so organized that although there is an enormous amount of work to be done there is a shortage of jobs?

Do schools really have to stress competition (if two people help each other, that’s “cheating”) and ranking (you “pass,” I “fail”)? What would society be like if education instead stressed co-operation and full development of the self as part of the whole community?

Is a barter- or money-based marketplace the only possible means by which we all can provide each other with what we need for a good life?

Why shouldn’t things of which there is an actual or achievable abundance – such as basic food stuffs, basic clothing, public transport, etc. – be made “free”? Of course, nothing is “free” since we have to work to produce things. However, many goods and services such as primary and secondary education, libraries, roads, water and sewage systems, utilities, etc. in many countries are out of the price system and free to the user. How many other common items could be free?

Abolition of the wage system, as the I.W.W. sees it, would profoundly change how we work and how our work affects our lives, our community, our planet. We want a society where everyone’s basic mental and physical needs are automatically met – a healthy, ecologically-sound society which battles against the formation of social hierarchies.

At present the wage system creates and perpetuates a wide range of injustices, drastically narrowing the potential of what it means to be a human being. Wages are necessary only in a society of compulsion. Abolition of the wage system is a step working people every place have to take if we are ever to build a better world, rather than. just exchange one set of bureaucrats and bosses for another.

Vancouver General Membership Branch of the IWW, 1984.

A look at the old labor movement slogan and what ‘fair’ actually means.

In Lansing, Mich., the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) union leadership fought a pitched battle with the Lansing City Council to push capitalist real estate developers to use union labor. When discussing the fight, Joe Davis, the union representative, proclaimed, “It’s important to have individuals work and get paid a fair wage. We have to make sure labor is valued.”

We hear statements like this from the leaders of the business unions all the time. For instance, “A fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work” has now been the motto of the mainstream labor movement since at least the beginning of the 20th century. On the face of it, this general demand for workers sounds like a good thing. We have to work for a living, and so long as that’s the case, we should be paid a fair wage for our efforts. We don’t want to be exploited. We want our fair share of the pie.

However, what is a fair day’s wages, and what is a fair day’s work? To answer this we have to think about the specifics of how our economy—a capitalist economy— operates. We can’t simply ask what feels morally fair or what the law says is fair, whether that be the federal minimum wage or the often discussed and calculated “living wage.” What is morally fair, and what is even fair by law, may be far from being socially fair. Social fairness or unfairness is determined by the material facts of production and exchange.

First we can ask, from the perspective of a boss—a capitalist—what are a fair day’s wages? The answer from this perspective is pretty simple. The labor market defines the capitalist’s role as a buyer of workers’ ability to work, and the employee’s role as the seller. The employee sells her time to the employer who in turn pays the employee in wages. The capitalist pays his version of a “fair wage”—the amount required for a worker with average needs to survive and keep coming back to work each day. Some bosses might pay a little more, some a little less, but on average this is the base rate of “fair” pay.

From this same perspective of a capitalist, then, what is a fair day’s work? A fair day’s work to the boss is the maximum amount of work an average worker can do without exhausting herself so much that she can’t do that same amount of work the next day. You, the worker, gives as much, and the capitalist gives as little, as the nature of the bargain will allow. As is probably obvious, this is a very strange sort of “fairness,” and probably not how any rational person would define the word. Let’s look a little deeper into this issue.

People who praise the great “free market” would say that wages and working conditions are fixed by competition between the buyers, the capitalists. Supposedly, capitalists are all competing for workers, so that competition inevitably leads to fair wages and working conditions. After all, the seller—the worker—theoretically has several options of employers to choose from. If a buyer doesn’t offer a price that a worker thinks is fair for her labor, then she can look for another job that pays better. By agreeing to the prevailing wage, so goes this line of argument, workers have essentially made the statement: “We think this is fair.”

One problem with this “logic” is that workers and bosses do not start on equal terms when they are buying and selling. It’s not like you’re selling an iPod on Craigslist, in which you can wait until someone pays the price you want. For most of us, if we don’t have a job, we can’t pay our bills, feed ourselves and our families, or heat our homes. Having employment is a life or death issue. It may not be life or death in the short term, but eventually if you can’t find a job or someone with a job who will help you out financially, you will not be able to buy the things you need to live, let alone the things you need in order to be happy and fulfilled.

It’s a very different story for the owners of the companies we work for. They have money in the bank, and if they don’t get employees tomorrow or even this month, they might be severely inconvenienced. Although their companies might take a hit in profits, they won’t risk anything like the consequences workers do. Their worst case scenario is far better than ours, so the free market lover’s idea of an “even playing field” is, in reality, a sick joke.

This isn’t the worst part of it. Bosses lay off workers when they develop new technology to replace employees and they lay people off when their profits plunge, as is the case in the current recession. As a result, workers lose their jobs way faster than they can be absorbed into other jobs. Today, there is a massive pool of unemployed workers and the capitalists, as a class, use unemployed working-class people against the rest of the class. If business is bad and there are few jobs for those of us who find ourselves out of work, some of us can collect a meager amount of unemployment money, while some turn to stealing and some lose their homes and are forced to beg for money on the street. If business is good and jobs appear, then unemployed people are immediately ready to take those jobs. Until every single one of those unemployed workers has found a job, capitalists will use desperate job seekers to keep wages down. The mere existence of this pool of unemployed workers strengthens the power of the bosses in their struggle with workers. Anyone who has ever heard a boss say, “If you don’t like it here, there are 10 other people I could hire to do your job,” will know how this plays out in terms of respect on the job. In the foot race against the capitalist class, the working class has to drag an anvil chained to its ankle—but that is “fair” according to a free market economist.

Now let’s take a look at how bosses pay their workers. Where does a capitalist get the money to pay our very “fair” wages? He pays them from his capital, his stored up funds from all the business he’s done, from all the goods or services his company has sold. Where did those goods and services come from in the first place? They came from the workers. The employees are the ones who worked to create those products or services that were then sold to consumers. The boss doesn’t do any work—he might oversee some of the workings of the company, but for the most part he sits on his ass watching as the work takes place. So we can say clearly the workers created the value that built the fund that they get paid from—a worker’s wage is paid from the product of her own work. Now, according to common fairness, you should get out what you put in, your wage should be equal to the value that you have created for the company through your work—but that would not be fair according to the values of a capitalist economy. On the contrary, the wealth you have created goes to the boss, and you get out of it no more than the bare necessities of life—a wage as low as the boss can get away with paying. So the end result of this supposedly “fair” race is that the product of the working class’s labor gets accumulated in the hands of those that do not work, and in their hands it becomes the most powerful means to enslave the very people who produced it.

A fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work! There’s a lot to be said about the fair day’s work too, the fairness of which is about as fair as these “fair” wages. It is also worth examining the role that unions play in affecting the rate of wages, but rarely the fairness of the wage process. We’ll be talking about these issues in future articles. From what has been stated so far though, it’s pretty clear that the old slogan has outlived any usefulness, and no one should take it seriously. The “fairness” of the market is all on one side—the side of the capitalist class. So let‘s bury that old motto forever and replace it with a better one: “Abolish the wage system!”

Nate Hawthorne and Matt Kelly

June 2012 issue of the Industrial Worker

On the wage system in capitalism.

We talked in our last column about the slogan “A fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work.” In capitalism, we can’t get many things we need unless we have money. There are really only two basic ways to get money: Hire someone to produce something which you try to sell for a profit, or get hired by someone to produce something, which they will try to sell for a profit. This is why no wages under capitalism can be truly fair. This is because the basic arrangement is already unfair. Under capitalism we are required to spend our time working for other people. Furthermore, the stuff that capitalists sell…workers made it. The capitalists’ profits generally come from the difference between the price they charge for the stuff we produce and what they paid us to produce the stuff. That difference is inherently unfair.

But it’s important to note that capitalists are constrained by the capitalist system, too. These constraints are often more powerful than the actual laws on the books. Whatever the laws on paper, the real law of the land in capitalist society is the law of profits. When the official laws line up with that law, then the official laws tend to be followed. When the official laws no longer line up with the law of profits, then the law of profits tends to win out. This is because the capitalist system rewards employers who reduce costs while keeping prices up. For workers this means that companies that pay employees less (and that spend less on having a safe, sanitary work environment) than their competitors will be more profitable. The system punishes employers who pay employees more than competitors. This will always happen under capitalism. That’s another reason why “a fair day’s wage” is always going to be limited.

Sometimes liberal or progressive capitalists, and more generally people who are in favor of capitalism, will become concerned that wages are too low and conditions are too bad. This is because capitalists need workers. The capitalist class needs there to be workers tomorrow, and in 10 and 20 years. Smarter capitalists and people who support capitalism sometimes realize that if wages get too low then workers may have a hard time coming back to work. You may know this from your own life if you have ever dug through the couch cushions to find bus fare to get to work, or if you’ve had to work long enough hours or in bad enough conditions that your immune system crashes and you get sick and have to miss work. And if wages get too low then in the long term workers might not have enough kids and provide their kids with the sorts of education and training that will make them be what employers will want in 10 or 20 years. Sometimes capitalists behave in ways that maximize profits in the short term but which have the potential to undermine the stability of the company or of capitalism as a whole in the long term. The recent global economic meltdown triggered by financial markets is another version of individual capitalists putting the short term goal of maximum profit ahead of the long term interests of the capitalist class as a whole.

Liberal or progressive capitalists and their supporters recognize that capitalists overall will be better off if there is a balance between the short term profits of individual capitalists and the long term interests of the capitalist class. This leads these progressives to call for fair wages. Capitalist “fair wages” means that individuals get paid enough that they can support themselves in order to keep on working. In the long term, “a fair day’s wage” means that the working class gets paid enough to keep having kids and raising them up so that there continues to be a working class. From our perspective, the perspective of workers, we want more money for our work. But we also need to recognize that wages and improving working conditions for some workers is often in the long-term interests of the capitalist class. This is why there are minimum wage laws and health and safety laws. This also accounts for the motivation of some capitalists to support initiatives like universal health care. They want to ensure that healthy and productive workers are available for the production of profit.

The labor movement has a long history of fighting against the constraints that capitalism imposes on humanity. There have been important changes in the specifics of the constraints imposed by capitalism. At the same time, obviously capitalism still exists and it still constrains humanity—working-class people especially. The AFL-CIO, Change To Win and other unions have always based their struggles on the goal of “a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work.” They have never once lifted any section of the working class out of wage slavery, nor have they ever tried. Similar to what we’ve seen with the liberal wing of the capitalist class, the improvements the labor movement has won have often helped to stabilize capitalism. Individual capitalists are often willing to work against the interests of their class if it means they can individually profit, which can make individual capitalists or small groups of capitalists into a threat to the system. Unions can sometimes function as a sort of immune system within capitalism. When unions organize to check particularly greedy capitalists who put their short term needs above the needs of their class, they reduce the extreme behavior of some capitalists who threaten to destabilize capitalism.

That doesn’t mean these unions are worthless or that we should not support their struggles. The labor movement has fought for and won very important changes in working-class people’s lives. To put it another way, the labor movement is a name for working-class people struggling to improve their lives, against the constraints imposed by capitalism, and there are very important successes that have been achieved. Many people would have a much lower standard of living without those successes. These improvements in standards of living apply mainly to union members, but to some extent there are improvements that have been shared with non-unionized workers as well. The eighthour day, regulations on child labor, the right to organize, workers’ compensation laws—for these things and more we owe a debt of gratitude to the brave men and women of the labor movement.

The improvements in working-class life won by the labor movement show that the constraints imposed by capitalism are not inevitable; demonstrating that the artificial limits that capitalism imposes on humanity can be pushed back and challenged. Obviously, organized workers will generally have better wages and benefits under capitalism. But the degradation of the entire working class is not about having better or worse wages, better or worse benefits. The degradation of workers stems from the fact that the working class doesn’t receive the full value that we produce by our labors and we have to be satisfied with a fraction of that value called “wages.” The AFL-CIO and the rest of the traditional labor movement is blind to this reality, and so can only ever help to make an inherently exploitative system a little easier to live in.

In the IWW, a union where our eyes are open to recognize this stark reality, we should recognize that some improvements, even hard-fought ones, can result in more stable versions of capitalism. Being aware of this can help us plan for what comes after a short-term victory. We especially need to make connections between our fights for improvements now and the fight to end capitalism. This means we must never really settle for any improvements. We don’t simply want a better life under capitalism, because “a fair day’s wages” is still unfair. We must always point this out and educate ourselves and each other about the ways capitalism limits working class people’s lives. We must also recognize that there is a ceiling on how much things can improve in a capitalist society.

The IWW organizer Big Bill Haywood once said, “Nothing is too good for the working class.” This echoes other radical slogans: “We demand everything!” and “everything for everyone!” Whatever we win, we’ll take it. We won’t feel grateful to anyone on high who “gave” it to us. As soon as we can we’ll fight for more, and we’ll join with our brothers and sisters elsewhere in the working class who are fighting, until we take it all.

Nate Hawthorne and Matt Kelly

July/August 2012 issue of the Industrial Worker