Book reviews – Hannah, Corbyn/McCluskey, Saini

Capitalist China and Socialist Revolution. By Simon Hannah. Resistance Books, 2023. 67pp.

This pamphlet begins with some indisputable truths: ‘The working class in China is massive – the largest in the world. But they often work in terrible conditions with few effective rights and no independent trade unions. They labour under an authoritarian government calling itself “socialist with Chinese characteristics”.’ Its author then goes on to further characterise modern China as a country run by a ‘pro-business’ party, which, while calling itself ‘communist’, is so only in name. Nor is he impressed by those on the political left who defend China simply on the grounds that its government has massively developed the country’s productive forces and in so doing has lifted millions out of absolute poverty. He points out that this process has not been a prerogative of China and that globally capitalism has ‘lifted millions of people out of abject poverty, whilst condemning millions of others to live in misery’. He goes on to say that ‘the Chinese state corresponds to all the definitions of a capitalist state’, in which ‘both the state sector and the private sector follow capitalist imperatives of growth’.

Nothing here at all that socialists would disagree with. But disagreement does start when he asserts that this state of affairs (ie, China being capitalist) only began in 1976 ‘with the economic and political reforms after the death of Chairman Mao’. The author does recognise that things weren’t great under Mao and that the various schemes adopted by his regime such as the ‘five-year plan’ and ‘the Great Leap Forward’ were abject failures that heaped suffering on the people and led to, among other things, mass famine. Yet, at the same time he definitely soft-peddles that disastrous rule, even referring to it at one point as ‘a new course towards socialism’, albeit one that didn’t go to plan. But little is said about that overall, with the main criticism reserved for what happened after Mao’s death when Deng Xiaoping took over leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and, as quite rightly observed here, opened up the economy to the world market, something he described, in a supreme exercise of smoke and mirrors, as ‘using capitalism to develop socialism’. The writer then goes into significant detail to show how this process of integration into the world market continued and intensified in the decades that followed continuing to the present day and how it was coupled with increasingly authoritarian political control by the CCP, which has managed, sometimes by brute force, to keep the lid on protest, as, for example, in the slaughter of students and workers at the Tiananmen Square protest of 1989. As for the current situation in China under the leadership of Xi Jinping, he quotes the words of a recent Hong Kong opposition activist: ‘Today’s CCP, with its fusion of both political and economic power, its hostility towards people enjoying basic rights of association and free speech, its xenophobia, nationalism, Social Darwinism, cult of a corporate state, “unification” of thought, etc., is now comparable to a fascist state’. And he points to the fact that China, in its mix of state and private ownership, has more billionaires than any other country in the world, while workers are largely denied independent trade unions and, if they protest, are likely to be arrested or battered into submission by the police.

None of this can be denied, but what is hard to understand is how the author can see redeeming features in what happened previously (ie, under Mao) and can somehow see what is happening now as fundamentally different from – and worse than – the repressive and tyrannical state capitalism that existed then. He correctly points to the fact that ‘state ownership does not equate to socialism’, but it did not under Mao either. Mao’s journey was just as much down ‘the capitalist road’ as that of his successors.

As to how China will develop in the future, the author rightly sees this as unpredictable, but avers that the ruling party may not be ’as homogenous and united as it pretends to be’ and its leader, Xi Jinping, not quite so impregnable as he may seem. So he does not see it as impossible that China may develop into ‘a liberal democratic capitalist state on the model of Western democracy’ or into ‘a Russian style capitalism controlled by a small and powerful aristocracy’. But, as he makes clear, any such arrangement would still be capitalism. As an alternative to this, he calls for a society ‘not based on profit but on need, social development and human capacity’. As to whether this can happen in a single country or whether it must be global, there appears to be some contradiction in his mind. The fact that he sometimes makes reference to ‘socialist countries’ suggests that he does not necessarily see socialism as a world system, as we insist it must be. At the same time he does talk about the need for ‘an international working class movement’, and the ‘Anti-Capitalist Resistance’ group under whose aegis this pamphlet is published states its aim as ‘social transformation, based on mass participatory democracy’. Whatever the case, it is clear that socialism, meaning a system of free access to all goods and services based solely on human need, cannot exist in just one country. It must, by definition, be a world society and one that has to be consciously brought into being and then organised cooperatively by a majority of workers who have taken democratic action to opt for it.

HKM

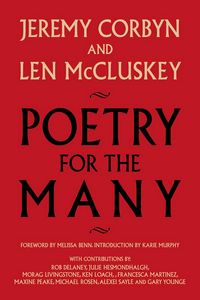

Poetry for the Many. Compiled by Jeremy Corbyn and Len McCluskey. O/R Books. 2024.

‘Poetry tells truths that often cannot be expressed in discourse or prose. It gives meaning to the inner-self and allows for people to think freely.’ So says Jeremy Corbyn in his opening remarks. He goes on to state ‘It can be just an expression of thoughts that may at first appear as random but, when written down on paper or screen, can become more coherent and take on a deeper meaning’.

Socialists are surely in favour of any means by which people are engaged in a process of deeper consideration of the world in which they live. Anything that challenges individuals to look beyond the glossy blandishments of the mass and social medias must be regarded as positive.

I first became actively involved with poetry as a writer and performer 50 years ago with the Tyneside Poets. The stated aim of the group was to encourage a widespread appreciation of poetry outside the walls of academia and the classroom. Through its regular meetings, readings and publications the Tyneside Poets group pursued its aims in a wide variety of settings and locations, giving opportunities for people, who otherwise would have been denied such, to publish and publicly read their own poems.

In the late 1970s I co-edited with Gordon Phillips (a fellow Tyneside Poet) two anthologies of poems by young people. Looking for a title for the collection we were inspired by a line in a letter accompanying one submission. Having expressed his wish to have his poem published he then pleaded ‘please don’t tell my friends’. This poignant request became that title.

In a world of rap and poetry slams it may be difficult to appreciate how poets and poetry were regarded by many back then. Tyneside Poets was not unique as similar groups flourished around Britain. The small press became a movement in its own right, a sort of democratisation of the word.

So, ‘Poetry for the Many’ is by no means a novel notion. But the title implies a certain difference. However unintentionally, it, implicitly at least, suggests a notion that is fundamental to reformist politics.

That is the idea of something of benefit being given to those who are presently deprived of it by circumstance. The many are passive recipients rather than active agents on their own behalf. That it is an anthology compiled by two well-known public figures invites the question whether it would have found a publisher had it been by A. Non and A. N. Other.

This is not to question the motives of Corbyn and McCluskey, but to reflect on the very nature of how capitalism influences all aspects of society. The back cover quotes Robin Campbell of UB40 fame, ‘Poetry and music for the many!’… ‘encouraging the working class to embrace and enjoy culture’.

This suggests a rather restricted view of what constitutes the working class. If we are using the socialist definition, the 99 percent or so who depend on the sale of their labour power for their means of life, then there is already a large number of that class who ‘embrace and enjoy culture’.

‘For the many’ was the slogan promoted by Jeremy Corbyn, his allies and supporters, during his ill-fated tenure as leader of the Labour Party. An apt comment on leadership is chosen, perhaps knowingly, by Len McCluskey, a poem by Roger McGough:

The Leader

I wanna be the leader

I wanna be the leader

Can I be the leader?

Can I? I can?

Promise? Promise?

Yippee I’m the leader

I’m the leader

OK what shall we do?

It’s almost possible to hear this in the voice of Lenin following the storming of the Winter Palace. Or maybe Corbyn after his surprise election to the Labour Party leadership. Perhaps it’s any leader confronted by the reality of administering capitalist society.

Compiling any poetry anthology is a subjective process. If the selected criterion is poetry for the many then questions of accessibility and obscurity come into play. After all the objective is to encourage through engagement rather than possibly discourage due to difficulty. Consequently, many of the poems included here are well known, Wordsworth’s ‘I wandered lonely…’, Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’, Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ and others similarly popular. If the purpose is to engage a new audience for poetry then these are good inclusions.

All the poems are prefaced with an introduction by whoever did the choosing. Reasons for the choice of poet and poem are given, along with the significance to each individual. This is the case for approximately three quarters of the poems. The final quarter is given over to choices by such as Ken Loach, Maxine Peake, Michael Rosen and Alexei Sayle amongst others.

The political ethos underpinning this anthology can be traced to its foundation. This was a gathering for the Politics and Poetry Event in Liverpool’s CASA club, October 2021. Karie Murphy in the anthology’s introduction sets the scene. ‘On the stage is a trio of stalwarts of the Left: Jeremy Corbyn, Len McCluskey and Melissa Benn.’

Thus the somewhat washed out and limp red flag is nailed to the mast. We do not doubt the sincerity of Corbyn and McCluskey in their love of poetry and their wish to bring others, undoubtedly many, to a similar appreciation.

However, from a political point of view, this is still poetry as a commodity people can, literally, buy into. Their role is that of consumers, guided by ‘…stalwarts of the Left’ a self-selected poetic vanguard.

A mitigating reply might be that as stated on the cover ‘All royalties from sales of Poetry for the Many will be donated to the Peace and Justice Project’. No matter how worthy a cause it does not confront the actual issue that peace and justice can only be achieved through abolishing capitalism, and not fine words.

To paraphrase Marx, ‘The poets have only interpreted the world…The point, however, is to change it’.

DAVE ALTON

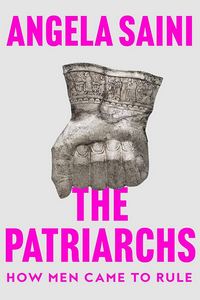

The Patriarchs: How Men Came to Rule. By Angela Saini. 4th Estate £10.99.

Friedrich Engels referred to the ‘overthrow of mother-right’ as ‘the world historical defeat of the female sex’, meaning that women became subordinate to men and ‘the woman was degraded and reduced to servitude’. This implied an earlier time where women had far more power and authority, in matrilineal or matriarchal societies. The Socialist Party’s 1986 pamphlet Women and Socialism criticised this account on the grounds that there was no universal stage of matriarchy and that relationships between men and women have changed over time to meet the needs of society.

In this book Angela Saini makes a similar point, that early societies varied greatly, and ‘the emergence of patriarchy could never have been a single catastrophic event’. A lot of material, in different places and at different times, is covered, but often it is hard to draw firm conclusions.

Societies where descent is traced through the female line are found in many parts of the world, though rarely in Europe. The Khasi community in north-east India, for instance, is matrilineal, with a child belonging to her mother, and men do not have rights over property or children. But it is not matriarchal, as family authority rests with the mother’s brother, though this power is not absolute. Some men have objected to this system recently, but others have defended it. In North America the Seneca have adopted a patrilineal naming system, but tribal membership remains matrilineal, despite the efforts of missionaries and government agents to institute a more patriarchal system.

Unfortunately, the book’s main claims are let down by an unconvincing chapter on the status of women in Russia and Eastern Europe under Bolshevism, in what is termed here ‘state socialism’. Abortion was legalised in the USSR in 1920, though this was reversed under Stalin in 1936, in order to boost birth rates, and it was made legal again in 1955. East Germany saw a massive increase in the number of crèche places, and by 1959 almost every pharmacist in the Soviet Union was a woman. On the whole, though, patriarchy was ‘dented’ rather than smashed. Saini does not discuss this, but the division into rulers and ruled was of course not even dented (see chapter 3 of our 1986 pamphlet for more on women in Russia.)

In Iran many women supported the movement against the Shah, but the Islamic Republic clamped down on women’s freedoms, with abortion made illegal and the wearing of the veil being mandatory. As this and other examples show, patriarchy is ‘being constantly remade in the present, and sometimes with greater force than before.’ And patriarchy is not a single phenomenon, rather there are plural patriarchies, existing in different ways in different cultures.

PB