Turkey’s ambivalent elections

Turkey’s modern political history is one of genocides, state-sponsored political assassinations, demonstrators machine-gunned by unknown actors or tear-gassed by police and army, and the Left arrested, executed, imprisoned en masse, or forced to flee: all under the ever-present threat of army intervention, with its military intelligence heavily exposed to the CIA.

Turkey’s modern political history is one of genocides, state-sponsored political assassinations, demonstrators machine-gunned by unknown actors or tear-gassed by police and army, and the Left arrested, executed, imprisoned en masse, or forced to flee: all under the ever-present threat of army intervention, with its military intelligence heavily exposed to the CIA.

And elections, such as this one.

Turkish political dynamics express themselves through a multiplicity of parties which then form coalitions to fight elections, which are essentially bipolar. The names of the parties shift as they fracture or are suppressed by the state: compared to European politics there is a bewildering turnover. Since 1982 Turkish courts have suppressed 19 political parties, violating the ECHR’s Convention on Human Rights in almost all cases it has reviewed, mainly for expressing Kurdish political interests. The two main reasons given are that the party is in conflict with ‘the indivisible integrity of the State with its territory and nation’, or ‘the principles of the democratic and secular republic’. This is a fair summary of the vague limits of Turkish political activity, though democracy gets shot on the court steps.

Deep state

Then there is the ‘Deep state’, a term which Turkey originated and Trump merely co-opted. This was exposed to the public in the Susurluk scandal, where a Turkish mafia assassin, his model girlfriend, the Istanbul chief of police, and a Turkish MP, were involved in a car crash (only the MP survived). But it was and presumably is a constant feature of Turkish political life: an unaccountable (except perhaps to the CIA) association of military intelligence, the criminal underworld, and enabling fascist political figures, originating as part of Operation Gladio but with its own autonomy. Its relative strength is demonstrated by its ability to slay those investigating them, including most probably a former prime minister, Turgut Özal, and avoid punishment. Its control of the Turkish heroin trade, worth more than the entire Turkish state budget at the time ($50 billion to $48 billion) accounted for much of their power, as well as their American allies in the shadows.

Closely linked with the military, and formed with its aid, are the ultra-right/fascist party, the MHP, and their youth/terror wing, the ‘Grey Wolves’. Opposing them is a strong ‘communist’ and ‘socialist’ tradition, often fragmented, often suppressed, often imprisoned. Their parties form new initials as quickly as the courts suppress the old ones. Not content to merely imprison them, in 2000-2001 the authorities forced them out of dormitory prison blocks, where they practised actually existing prison communism, into small three-person cells. There were mass protests, hunger strikes and deaths.

Always there is the issue of religion, though the matter is more complex than it appears: one is reminded of the fable of the Wind and the Sun. The state was aggressively secular, and aggressively against minorities, most of whose identity was in part religious. Politically speaking, expression of religious identity was and is thus in part a matter of cultural rather than religious fervour. Also, secularism is associated with wealth, the middle class, and the western cities of Turkey. As the poor agricultural workers of the Turkish heartland migrated to the cities, religion became a defining, comforting feature of their mutual character as they lived in the spaces left to them, in gecekondus (shacks built overnight) or other poor housing.

Then there are the Kurds, Alevi and Sunni. A genocide in the 1930s killed or displaced many Alevis from their home in Dersim, which was renamed, on maps at least, to Tunceli: the very name, ‘Bronze Fist’, of the genocide operation. And there is the ongoing war against Sunni Kurds in the South East. These remain politically relevant. There are many other nationalities in Turkey, but they were brutalised long ago.

Failed coup

Recent history, since the election of Erdoğan’s AKP (Justice and Progress Party) in 2002, has seen several changes within this continuity. Corruption has moved to private industry, where new corporate players have emerged: especially in the construction industry, largely responsible for the Eastern earthquake calamity where their cheap and profitable buildings fell down. The army has been suppressed, with mass show trials in the Ergenekon scandal and others, more so since the failed 2016 coup. From a situation where the Army had the standing power via the National Security Council to suppress civil politics, essentially a permanent coup option, now Erdoğan, their victim in the past and now rid of them, has adopted a similar bullying role as president in lieu of restoring civil society. Fethullah Gülen, master of a ‘parallel state’, a network of civil servants and army officers, once Erdoğan’s ally in the shadow war for the deep state, is now an enemy of the state exiled in the US.

In 2017 Erdoğan strengthened the presidency in a constitutional referendum, granting him powers to appoint and sack ministers and issue executive decrees. And in 2018 the last election was carried out still under the ‘state of emergency’ declared 5 days after the coup attempt. All in the context of war at home and abroad, mainly against Kurdish aspirations but also seeking to gain from Syria’s woes. Turkey has a seat at the table in NATO’s proxy war in Ukraine, and its restive place in NATO is a matter for constant Western scrutiny and cajoling, especially over the Syrian war, and purchasing Russian arms. All in the context of economically bizarre policies that have seen inflation wipe out savings and drive the population to penury. But the most important recent event is the catastrophic earthquakes of February this year, killing 50,000 and leaving 1.5 million homeless. This last was thought to set the context for the election, making Erdoğan’s general misrule an electoral focus in itself that might attract the disaffected/dispossessed right and harden support among the newly homeless in the South East.

Secular opposition

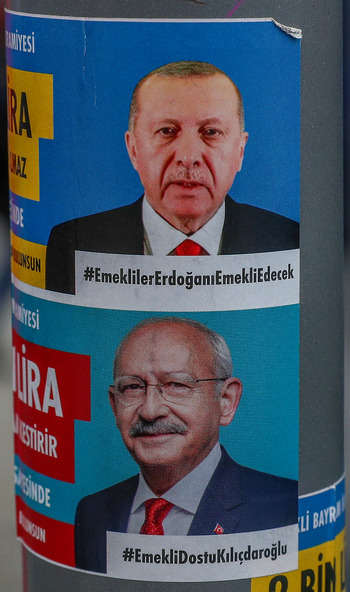

And so to 14 May 2023. There are three main electoral alliances, two standing for the presidency as well, the candidates being Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (AKP) and Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (CHP). The ruling right-wing ‘People’s Alliance’ of the AKP and the MHP (Nationalist Movement Party), versus the ‘Nation Alliance’ of the CHP (Republican People’s Party) and five other parties, with support from most other parties from centre-right to ultra-left. There are tensions in both camps – the MHP for example is both virulently opposed to any compromise with the Kurds, such as the current peace process, and also its Turkic ultra-nationalism clashes with Erdoğan’s Islamic dreams. As always though the right is far more cohesive than the centre and left, strange bedfellows united only in opposition: the CHP is the original party of the Turkish state, of Ataturk, and still professes the secularism, nationalism and capitalism that most of its bedfellows in some way disagree with.

The second and only other substantial party in their alliance, the İYİ Parti (Good Party) is a splinter from the MHP, professing to be civic nationalists instead of Turkic nationalists, and good followers of Atatürk: their voter base consists largely of the right wing who are disillusioned with the existing right wing, in other words a classic populist party. This ability of a fragment of the MHP to thus realign leftwards gives some idea of the complexity of Turkish politics, even though most voters will have an imperative which eventually dictates their political choice. The third alliance is the Labour and Freedom Alliance, egalitarian progressives, but almost entirely composed of HDP (Democratic Party of the Peoples) candidates expecting the state closure of their party and so standing as Yeşil Sol (Green Left) candidates. (In the aftermath of the failed 2016 coup more than 10,000 HDP members were imprisoned, including their leaders, on vague accusations of being supporters of terrorism). They are backing Kılıçdaroğlu for president rather than splitting the vote. But while wishing to see the back of the AKP and MHP, they have no reason to love or trust the CHP who when in power suppressed them just as savagely, and so are merely advising their supporters to vote for cholera instead of typhoid in the presidential election.

And the result? In parliamentary terms, Erdoğan’s People’s Alliance has a clear majority, of 322 seats against the Nation Alliance’s 212 and the Labour and Freedom Alliance’s 64. Presidentially also, it would seem that Erdoğan has survived. Neither candidate having 50 percent, the presidency goes to a second round: but with 49.51 percent of the vote to Kilicdaroglu’s 44.88 percent in the first round, the presidency seems all but his to keep. (There was a third candidate, Oğan, with 5 percent, a former contender for the MHP leadership).

The last act will be bruising. Erdoğan used his post-election speech to label his opponents as terrorists, setting the tone. And the earthquake survivors? They have to vote from their registered homes. That means that in order to vote they will have to travel back once more to those ruins from wherever they are billeted in Turkey, at no mean expense of money or time. Exhaustion, as always, tends to work for the incumbent. Time and fate is on Erdoğan’s side.

SJW