Socialism, Free Speech and ‘Cancel Culture’

Ten years ago, I found myself the recipient of several angry emails, all sent to my work email address. My crime had been to write a letter to a student newspaper in which I criticised a student’s proposal to make it compulsory for university staff to wear a red poppy. The details of this affair aren’t relevant here and my opinions about the red poppy are easy to find elsewhere (in summary: no communist or socialist should have anything to do with the thing). Presumably unaware of the irony, one outraged nationalist emailed me to say that the Second World War was justified, since it guaranteed ‘the freedoms that we enjoy today’, and also wrote to my line manager recommending that I be disciplined for asserting otherwise. For many on the right, this is what free speech really means: freedom of speech for me and for the people who agree with me.

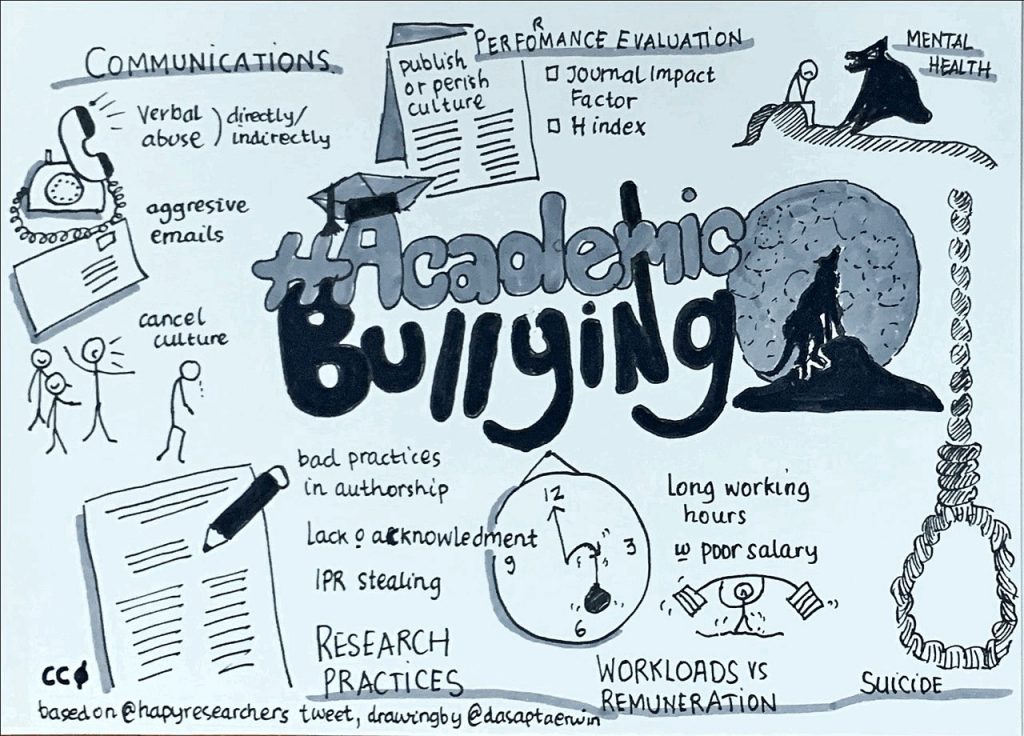

But some – perhaps an increasing number – of those on the left of politics are also eager to no-platform or ‘cancel’ their real or supposed ideological opponents. Weaker manifestations of cancel culture include ostracism, blanking, ghosting and gossip-mongering – the tactics of an online left that often seems hellbent on plumbing the depths of infantilism, narcissism and moralism. Sometimes leftists go even further, attacking the validity of free expression itself and seeking to curtail it. In the ‘wokest’ corners of the web today, appeals to the principle of free discourse are often mockingly parsed as ‘muh freeze peach’ and the essential foundation of radical political debate – being able to write or say what you think in dialogue with (or opposition to) others – is more and more ridiculed as the outdated obsession of centrist squares, out-of-touch boomers, or, to use the argot, ‘literal fascists’.

Left-wing suspicion of free speech is nothing new. To cite a classic example, Herbert Marcuse’s essay on ‘Repressive Tolerance’ (1965) attempted to justify the denial of freedom of speech and organisation to ‘groups and movements which promote aggressive policies, armament, chauvinism, discrimination on the grounds of race or religion’. Such groups and movements are still with us, of course, and they should be countered at every turn. But we would argue that for socialists, it doesn’t make sense to suppress repellent social and political views – something Marcuse himself recognised would be ‘undemocratic’ (albeit, in his view, a necessary step towards achieving a more genuine democracy). In general terms, expressions of prejudice and hatred should be permitted, not because there exists some ideal ‘free market of ideas’, but because it is only by discussing and debating them that their vile nature can be exposed. As John Milton famously put it in his Areopagitica ‘Let [Truth] and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter? Her confuting is the best and surest suppressing’.

Left-wing suspicion of free speech is nothing new. To cite a classic example, Herbert Marcuse’s essay on ‘Repressive Tolerance’ (1965) attempted to justify the denial of freedom of speech and organisation to ‘groups and movements which promote aggressive policies, armament, chauvinism, discrimination on the grounds of race or religion’. Such groups and movements are still with us, of course, and they should be countered at every turn. But we would argue that for socialists, it doesn’t make sense to suppress repellent social and political views – something Marcuse himself recognised would be ‘undemocratic’ (albeit, in his view, a necessary step towards achieving a more genuine democracy). In general terms, expressions of prejudice and hatred should be permitted, not because there exists some ideal ‘free market of ideas’, but because it is only by discussing and debating them that their vile nature can be exposed. As John Milton famously put it in his Areopagitica ‘Let [Truth] and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter? Her confuting is the best and surest suppressing’.

We understand the appeal of cancel culture. After all, many of the most prominent free speech advocates in today’s public sphere are unpleasant conservatives such as Toby Young, who seems to pop up every five minutes on a British television channel to complain that you can’t say anything these days. But we should not embrace cancel culture just because right wingers oppose it. For one thing, free speech, as Thomas Scanlon argued long ago, is a good in itself, regardless of any consequences its exercise might have: this is because freedom of expression – including the freedom to hear others’ speech and make judgements about it – is important to us as rational, autonomous persons who can and should be able to make up our own minds about particular issues.

Moreover, it’s not clear that cancelling even works very well. The conservative and alt-right wingnuts and hatemongers who complain the loudest about being no-platformed – we’re thinking here of Young, Katie Hopkins and Tommy Robinson – are actually well-connected and powerful operators who, when cancelled, usually have little difficulty in finding alternative outlets for their opinions. Depriving such characters of their platforms is therefore generally counter-productive: all too often, it only allows them (and their deluded working-class supporters) to posture as the victims of a left-wing PC purge before trotting off to their next lucrative media gig. Cancellation does not starve these toxic edgelords of the oxygen of publicity; quite the opposite, in fact.

And what about the less elevated targets of cancel culture? Cancellation can be devastating for the less well-connected. It is becoming quite commonplace for ordinary people who offend against dominant public opinion on issues such as trans rights or Brexit to suffer reputational damage or to lose work and income . And there is little doubt that such personal and financial ruination is often intended by the cancellers. Indeed, the hostile environment created by cancellation aligns perfectly with the individualist, aggressive, competitive dynamics of contemporary capitalism – the ‘abyss of failed sociality’ as Axel Honneth has so cheerily put it – and the social sadism and ‘humilitainment’ that now mars large parts of mainstream media culture.

On social media, cancel culture often involves the vicious policing of speech, pile-ons and denials-of-service for the most minor of offences against political orthodoxy by relatively powerless individuals. As Kristina Harrison has put it , cancel culture, in its dismissal of nuance and dissent, tends to elevate ‘not debate and politics but moral absolutism, authoritarianism and hysteria, the tools of the witch-hunter’. Like the witch-hunter, the canceller moves readily between criticising the ambiguous behaviours or statements of her targets to making essentialist assertions about them, so that public figures or social media influencers who make misguided, ambiguous or problematic remarks about, say, racial or trans issues automatically become racists or transphobes. This point was made well by the late Mark Fisher in his critique of left-wing call-out culture, ‘Exiting the Vampire’s Castle ‘. Veteran BreadTuber Natalie Wynn (aka. Contrapoints), herself a prominent cancellee, makes the same and many other points in her far-reaching critique of the same.

And it should go without saying that Karl Marx himself would not have been impressed by no-platforming and cancel culture, although some leftists seem to be confused about this. A meme recently on Facebook consists of a four-panel cartoon depicting alt-lite rent-a-gob Milo Yiannopoulos moaning to Karl Marx about violations of his freedom of speech. In the final panel of the sketch, Marx silently picks up Milo and throws him over a clifftop. It’s a fun image, to be sure; but it’s also misleading. In reality, Marx fiercely defended freedom of speech. In ‘On the Freedom of the Press ‘ (1842), for example, Marx, with his usual sarcasm, ventriloquised the Prussian press censors of his day, mocking their hypocrisy: ‘Freedom of the press is a fine thing. But there are also bad persons, who misuse speech to tell lies and the brain to plot. Speech and thought would be fine things if only there were no bad persons to misuse them!’ In fact, Marx opposed censorship throughout his life. And anybody suspecting Marx of capitulating to liberalism in this regard should think again. As Eric Heinze argues, Marx defended free speech not as a bourgeois right, but as something more fundamental: a foundational philosophical praxis that makes possible the very discussion of rights.

And it should go without saying that Karl Marx himself would not have been impressed by no-platforming and cancel culture, although some leftists seem to be confused about this. A meme recently on Facebook consists of a four-panel cartoon depicting alt-lite rent-a-gob Milo Yiannopoulos moaning to Karl Marx about violations of his freedom of speech. In the final panel of the sketch, Marx silently picks up Milo and throws him over a clifftop. It’s a fun image, to be sure; but it’s also misleading. In reality, Marx fiercely defended freedom of speech. In ‘On the Freedom of the Press ‘ (1842), for example, Marx, with his usual sarcasm, ventriloquised the Prussian press censors of his day, mocking their hypocrisy: ‘Freedom of the press is a fine thing. But there are also bad persons, who misuse speech to tell lies and the brain to plot. Speech and thought would be fine things if only there were no bad persons to misuse them!’ In fact, Marx opposed censorship throughout his life. And anybody suspecting Marx of capitulating to liberalism in this regard should think again. As Eric Heinze argues, Marx defended free speech not as a bourgeois right, but as something more fundamental: a foundational philosophical praxis that makes possible the very discussion of rights.

Today, we socialists make up a tiny minority of the population and we have very little political and social clout. To change this situation, we need to be able to explain to other members of the working class what socialism is and why everybody will benefit from it. Sometimes this seems like an impossible task: even in relatively ‘open’, liberal societies, the major media organisations, as well as all the other institutions of capitalism, are overwhelmingly ranged against us and communist ideas are vilified, marginalised and misrepresented in both right- and left-wing media. But we must make use of whatever relatively democratic spaces and opportunities do exist to shout about socialism. To attempt to deny free speech to our opponents simply on the grounds that they hold repellent or false views, meanwhile, would be unprincipled and counter-productive; ultimately, it would only make it even easier than it already is for those in power to silence us.

S.H.

2 Replies to “Socialism, Free Speech and ‘Cancel Culture’”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Books banned locally in the U.S. because of “woke” concerns have included To Kill a Mockingbird and the works of Mark Twain.

The far Left, as well as the far Right, have always had a problem with free speech, especially the Leninists.

Mao’s book burning campaign was responsible for hundreds of thousands of tonnes of books and historical records, literary works etc. being destroyed, dwarfing a thousandfold all the book burnings of Europe.