The Lessons of Charlottesville

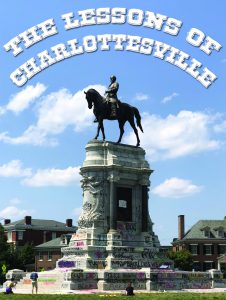

We are approaching the third anniversary of the Unite the Right rally that took place in Charlottesville, Virginia, on 11 and 12 August 2017. These events are particularly noteworthy today as we are seeing something of a repetition. Several white supremacists, neo-Nazis, neo-Confederates, Klansmen, self-proclaimed members of the alt-right, etc gathered, supposedly to protest against the removal of a statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee. What might have been justified under ‘defending American history’ led to a racist and violent demonstration that resulted in the murder of a counter-protester, Heather Heyer. Today, following the Black Lives Matter movement, there is a continuation of the same discussion. In the UK, a statue of Winston Churchill has been defaced with the statement ‘was a racist’ under his name. Debates go on about whether a statue of Lord Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Scouts and admirer of fascism, should be left up. Of course, many have come out of the woodwork to defend the statues, with more rationalisations than countable. Perhaps less has been learned from Charlottesville than one might hope.

We are approaching the third anniversary of the Unite the Right rally that took place in Charlottesville, Virginia, on 11 and 12 August 2017. These events are particularly noteworthy today as we are seeing something of a repetition. Several white supremacists, neo-Nazis, neo-Confederates, Klansmen, self-proclaimed members of the alt-right, etc gathered, supposedly to protest against the removal of a statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee. What might have been justified under ‘defending American history’ led to a racist and violent demonstration that resulted in the murder of a counter-protester, Heather Heyer. Today, following the Black Lives Matter movement, there is a continuation of the same discussion. In the UK, a statue of Winston Churchill has been defaced with the statement ‘was a racist’ under his name. Debates go on about whether a statue of Lord Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Scouts and admirer of fascism, should be left up. Of course, many have come out of the woodwork to defend the statues, with more rationalisations than countable. Perhaps less has been learned from Charlottesville than one might hope.

Jason Kessler, an American neo-Nazi, organised the demonstration against the decision to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee from Charlottesville’s Lee Park. This became a focal point for various white-supremacist movements, with notable members of the ‘alt-right’ like Richard Spencer joining in. Quickly, more and more far-right support for the organisations started pouring in, turning into a broad-church racist movement. Chants such as ‘Jews will not replace us’ and the Nazi slogan ‘Blood and Soil’ began to sound. The Ku Klux Klan began to participate. The ‘Proud Boys’, a fascist group that organises and promotes political violence, also joined. Under freedom of expression and assembly, an extremist demonstration hundreds-strong was enabled.

Of course, this was met with significant resistance. Anti-racist and anti-fascist counter-protestors also organised, despite the lack of police protection that the right wing enjoyed. Ecclesiastical groups, social-democrats, civil rights activists, anarchists, and more gathered in Charlottesville to both oppose the racists and defend those they felt were threatened. Police action often simply ignored violence against counter-protesters (when it was not contributing to it). Violence then erupted between the protesters and counter-protesters. At its height, a white supremacist, James Alex Fields Jr., drove his car into a group of counter-protesters at about 30 mph before reversing into more. He killed a civil rights activist, Heather Heyer.

There is much in this that is frightening, including the fact that similar events are still happening. Something worth dwelling on is how racist sentiment can divide the working class, pitting its fragments against one another.

This is perpetrated most viciously by people like Richard Spencer, who believe themselves to be above the working class. They try to appeal to the white working class, focusing on the ‘race’ divisions which are very prominent in America. This, in turn, makes those captivated deny their identity as members of a class and buy into their supposed identity as a race. They are then more easily tempted to associate with people like Richard Spencer, or even Donald Trump, who hold the working class in utter contempt. The fact that the mainstream right and the fringe are not disconnected is well supported by Trump’s refusal to condemn the white supremacists, claiming that there were ‘very fine people on both sides’: being goaded by ideas like race simply masks the material reality of the class structure of capitalism, obscuring it behind veils of ethnicity and religion.

The white supremacists use the language of ‘degeneracy’, condemning those deemed unworthy by them to service towards the higher classes (which, of course, includes them). Some appeal to an idea of a golden age taken away from these noble few by the corruption of the masses. Some members of the working class might even believe this, thinking themselves or others to be inferior to the elites. If this attitude became widespread, it would be one of the biggest threats to the possibility of socialism. Socialism depends upon the consciousness of the working class of their own potential to liberate themselves.

Marx, early in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, writes that ‘the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionising themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honoured disguise and borrowed language’.

The statues of past figures, supposed heroes, do weigh like a nightmare on our brains. There are so-called great men. This shouldn’t be the case. There are people who have made impacts on history, to be sure, but supported by innumerable others whose names are lost to us. Hero worship is quite close in character to the rhetoric of the extreme right, who want to convince the masses of certain groups’ superiority. Furthermore, the picture of history presented by statues is significantly distorted, as it is one guided principally by the attitudes of the ruling class. This is rarely an accurate picture of events. Which people are chosen to be commemorated and which are not is often quite telling. This will do nothing but lead the working class to tacitly accept class structure.

There are still lessons to be learned from Charlottesville. Besides the point that ‘it could happen here’, there are more general issues about the class struggle. White supremacy and other forms of obscuring the class war will always focus on dividing the working class and trying to convince them of their own inferiority. Of course, the necessity of class oppression is a lie told again and again to maintain power. To draw from the opening of the Eighteenth Brumaire again, hopefully the tragedy has already passed and we only have to deal with the farce. Unfortunately, the reinvigorated debate about statues suggests otherwise. While we are in the thrall of the past, there is limited progress to be made. The mainstream debate is limited between whether we should have a statue of this person or that person or not, but there is a deeper question to be asked about why we have statues at all. We’d be better off realising that there are no singularly great men. Serious change is brought about through massive popular movements acting together, not through the enlightened leadership of the few.

MP SHAH