Proper Gander: Can’t A Cleaner Like Avocados?

‘Middle class’ is a term which everyone recognises, but the more you pick apart at its meaning, the more meaningless it becomes. It’s often used to refer to people with ‘professional’ jobs or who work in ‘business’ with a reasonable salary, contrasted with ‘working class’ when used to denote people who do physical labour and who have a low income. But what about admin staff in ‘business’ who have a smaller wage than a builder? And isn’t all labour physical anyway? The ‘middle class’ have to work as much as ‘working class’ people do, even if they do it wearing smarter clothes than overalls. In other words, the vast majority of us are working class, whether or not we identify as ‘middle class’.

Making a distinction between ‘middle class’ and ‘working class’ throws up all sorts of confusions, so it was fitting that BBC2’s recent How The Middle Class Ruined Britain was a confused hodgepodge of a show. It was put together by Geoff Norcott, who has found his niche as a ‘Conservative voter, leave voter, working class’ comedian. His definition of ‘middle class’ is someone who watches foreign-language films and who‘likes a protest march so long as it’s followed by a spot of light brunch’, probably involving avocados (can’t a cleaner like avocados?). His main charge against the ‘middle class’ is the generalisation that ‘they’re hypocrites because they claim to be virtuous and caring and yet simultaneously they are doing things that serve their self-interest against other people’s’.

He finds an example of this in attitudes to schooling. He says that ‘middle class’ people claim to be fans of the comprehensive system, but wouldn’t want their own children to go to any old comp filled with hoi polloi. Instead, he argues that the ‘middle class’ resort to sneaky tricks to ensure their offspring get enrolled at schools with a decent reputation: ‘nicking the best school places is their version of benefit fraud’. Tactics include signing up with a church just to qualify for a faith school, and pretending to live in the catchment area of a preferred school by borrowing the address of a (wealthier) friend or relative. Havering Council employs ‘a dedicated team of super-sleuths’ to investigate suspicious applications for school places, which Norcott likes to make look like something from a cop show. Some parents have to resort to fibs and scams to get a school place because parts of the educational system aren’t open to all, and these are schools which have better resources. Schooling is subject to the same scarcities and divisions that other aspects of society are, so people are pushed into competing for what’s best.

Norcott says that ‘middle class’ people’s attitudes to comprehensive schools are similar to those about social housing: something they say they want, just not near them. He rightly points out that new housing developments don’t tend to include many council or housing association-owned properties, or those which are otherwise cheaper than ones aimed at ‘young professionals’. This prices many people on lower incomes out of newly-gentrified areas, which you would have thought an ‘aspirational’ Tory like Norcott would approve of. While he at least acknowledges his own hypocrisy here, he goes for the wrong targets in those he criticises over the issue. He dislikes what he calls the ‘hard left’ who engage in protests against building developments. When he meets a group of protesters in Deptford, London, he patronises them about their placards and songs, and raises an eyebrow when he can’t think of a punchline. These protesters don’t do themselves any favours, though, by carrying out a ‘symbolic salt ceremony’ which involves one of their more eccentric number sprinkling salt on the pavement ‘to ward away the greedy evil spirits’. He then meets a ‘top dog’ from a Labour council to challenge the ‘posh boy’ about social housing still being too expensive, even though the councillor is just a very small cog in a very big machine. The real problem here is that housing is a commodity, and can’t be anything else within capitalism, whatever councillors and protesters prefer. Cheaper houses and flats, including those owned by councils or housing associations, don’t rake in much profit, and so developers are bound to build more swanky pads which do.

He says that ‘middle class’ people’s attitudes to schooling and housing show how they like to keep those on lower incomes at arm’s length, and then he jumps to another example of this: a dating app aimed only at those who were privately educated. He goes to a ‘fancy dating event’ where he pays £16 for a pint and realises that people tend to associate with others from similar economic backgrounds and those without much money get priced out of wealthier social circles.

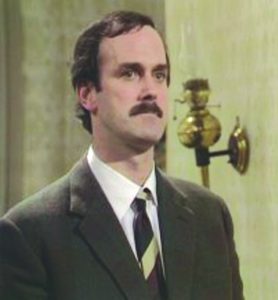

Basil Fawlty – the

satirical archetype of

the middle-class

The same applies to Westminster. It’s pointed out that these days, far fewer Labour MPs come from lower-income backgrounds compared with the past (Norcott doesn’t cite figures about the backgrounds of Tory MPs, unsurprisingly). He meets an exception to this, Gloria De Piero from Ashfield in the East Midlands, who acknowledges that the things discussed in parliament don’t address most people’s concerns. While it’s true that the working class don’t have enough of a political voice, MPs coming in from outside the Oxbridge bubble wouldn’t have any more ability to reform capitalism than any other. Even if they sincerely aimed to represent and help out their more disadvantaged constituents, they’d soon get unstuck by bureaucratic inertia and, above all, the dictates of the economy.

How The Middle Class Ruined Britain highlights some of the ways which wealth shapes capitalist society, from the kinds of houses which are built to the backgrounds of those with more power. But to see them you have to look past Norcott’s own prejudices and misperceptions. The conflict isn’t between ‘middle class’ and ‘working class’ – it’s between the majority and the system itself.

MIKE FOSTER