The Police: Bourgeoisie’s Boot boys?

During the 1984/85 miners’ strike it was the police who were the state’s storm-troopers in its assaults upon strikers. The brutal treatment they dished out to the pickets to intimidate them and their families caused an outcry. It drew attention to the extent that the capitalist class would use the powers of the state to protect its own interests. The criminal law was enthusiastically applied against the miners even though their picketing was not an offence.

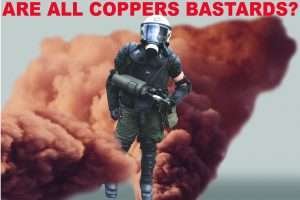

Those who have been on a protest march and been on the receiving end of a truncheon will share the same perspective as the persecuted miners, that the police are the hired thugs of our class enemy. The police are a class creation. We should know that the police were created by the ruling class to control the working class, not help them. They’ve continued to play that role ever since. We don’t want better policing. We understand only too well that they do not work for us and they never have. We want to get rid of the police in their current form entirely, and we want to live in a world where a repressive force is not necessary.

Among many communities there exists a lack of confidence in the police and little trust in their accountability. The police have come to be regarded by many on the Left as impermeable to socialist ideas, yet the fact remains, however, that the police are made up of members of the working class who, too, are required to sell their ability to work in whichever way they can. Like any other wage slave, the police have to do what their employers – the state – order them to do. The Socialist Party does not seek to pick on the monkey but targets the organ-grinder. The Left see the police as the enemy, but why single out one section of the working class as the source of our problems? The Left advances the idea that any attempt to establish socialism democratically and peacefully through the constitution will result in the police being used, along with the armed forces, to suppress that movement.

This argument assumes that police have economic and political positions apart from the rest of society and hold pro-fascist sympathies. However, members of the police force usually live in the community and seek its approval and respect and will often turn a blind eye to the law if it is in conflict with what the community thinks is right. For sure, many in the police hold obnoxious political opinions, but consider just how often these reflect the prejudices of other workers. The personal views of the police will not change until the way most people think changes and the indoctrination that many of our fellow-workers have suffered is undone. Our case is that those in the police share much the same attitudes as other workers and when these workers understand and desire the socialist alternative the same ideas will be accepted as much by the police. The police are as susceptible to socialist ideas as any section of our class.

Police strikes

That police are subject to the ideas prevailing in other sections of the working has been illustrated recently in other countries such as Bolivia (2012), Brazil (2008/2013), Argentina (2013), Portugal (2013), Iceland (2015) and Ireland (2016) where police have been protesting against their conditions or going on strike.

We have seen similar occasions even here in the UK. In 2008 and 2012 industrial action of sorts took place when police held protest marches. In 2007 police officers in Britain were banned from taking strike action or even discussing it. However, this year the rank and file voted overwhelmingly to explore the option of lobbying for full industrial rights if their claims were not met. ‘The feedback from our members is that we are rapidly approaching the situation where they want to bite back,’ a spokesperson said. ‘If we are to be treated no differently from other public sector workers, we need to explore whether we should have the same rights as other public sector workers.’

A hundred years ago, in 1919, police shared the heightened discontent of other workers.

In the US, Boston police officers went on strike on 9 September. They sought recognition for their trade union and improvements in wages and working conditions. The strikers were called ‘deserters’ and ‘agents of Lenin.’ All of Boston’s newspapers called it ‘Bolshevistic.’ The police strike ended on 13 September, when Commissioner Curtis announced the replacement of all striking workers with 1,500 new officers, who were given higher wages. The strike proved a setback for labour unions. No police officers in the US went out on strike until July 1974, when some Baltimore police, estimated at 15 to 50 percent of the force, refused to report for work for several days as a demonstration of support for other striking municipal unions.

As mentioned in May’s Socialist Standard, Winnipeg’s City police were supportive of the general strike there and were all dismissed for expressing support and for not signing a loyalty pledge not to take part in the strike.

In Belfast in 1907, the local police had mutinied against their instructions to safely escort blackleg strike-breakers during the dock-workers dispute which then led to their own pay rise demands. But as always there was a high price to be paid for that militancy. When the police union was outlawed by the Police Act of 1919 a national strike was called despite the fact that less than half the police were members. In Liverpool 932 out of 1256 struck. Riots took place where looters fought with soldiers and special constables, while a battleship and two destroyers steamed from Scapa Flow to Merseyside. The strike collapsed and every single striker was dismissed, never to be reinstated. Besides unemployment it meant eviction from a home and loss of pension.

A second police strike started on 31 July, 1919. It was a disaster. Only about 1,000 men struck in London, all of whom were instantly dismissed, and although a bitter struggle continued for some time – for example, strikers broke into the Islington section house to force the inmates to join them, eventually being forcibly ejected – the strike was absolutely crushed, and along with it the Police Union.

There were numerous arrests during the strike, and there were even a couple of sympathetic stoppages – of railwaymen at Nine Elms, and the tube motor men. One other interesting feature of the dispute was when Inspector Dessent of Stoke Newington Station, the only Inspector to strike, formed his men up in a body and marched them to the main strike meeting at Tower Hill.

The sacked men never got their jobs back, but many of them became active in the labour movement. After the defeat, the Herald League’s paper, Rebel, noted a large influx of new members from the Police Union. Tommy Thiel, on whose behalf the first strike had been fought, joined the Communist Party, as did a number of others. A local striker, Henry Goodridge, joined the Labour Party and eventually became Mayor of Hackney. Another Islington man, Sergeant William Sansum, who had been arrested and bound over during the 1919 strike, was arrested again for his support of the General Strike in 1926. Sansum, by this time a boot salesman, got three months in prison.

There had been considerable support for the 1919 strike from the labour movement, but many supporters, looking back on police harassment, or police inaction while they got bashed by jingoes, felt a bit awkward – to put it mildly – with their new allies.

Antisocial behaviour in socialism

If, in a socialist world we do have an organised body akin to the police, then this must be a service working in the interests of the people and be there to protect the people and society against a handful of dangerous individuals, not be there to protect a few individuals against society like the police force which we have under capitalism today.

We don’t take the totally utopian view that there will be no antisocial acts whatsoever and everybody in socialism will be angels. Crimes of passion could still take place. There will still be traffic ‘police’ ensuring safety on the road but it may be undertaken by car break-down rescue or highway maintenance patrols. There may well still be a formal trained organisation for crowd management at public events but they would be more like the stewards we have now. Psychiatric services have certain compulsory powers to prevent self-harm and harm to others for those with mental health problems – those involved can see how their work can be adapted and applied when cost is no longer an issue. Likewise those currently in the prison industry may raise alternative possibilities for those classed as a risk to society but with no treatable psychological disorder. Maybe some council departments will exercise ‘policing’ roles on antisocial behavior, just as they do now by mediating between feuding neighbours or sound abatement complaint squads in regards to noisy partying. Some form of detective/forensic department might well still remain to investigate what antisocial acts occur, but they would be more like accident investigators, sleuths in tracking down the culprit or cause, specialist Sherlocks. Either way, the coercive role of the police would be redundant, and the riot shields and batons would disappear into museums to stand alongside the swords and suits of armour.

ALJO

For a contemporary account of 1919 police strikes, see the June 1919 Socialist Standard: www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/1910s/1919/no-178-june-1919/bobbys-discretion/