Proper Gander: The Hand-Made Tale

When we’re stuck at work, stressed out and fed up with the usual hierarchies and procedures, who hasn’t daydreamed about doing something more imaginative and fulfilling? Days spent not being a small cog in someone else’s machine, but doing what we’re passionate about to make an end product of which we can be proud.

The Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries recognised that work could be more satisfying than what it has become in capitalism. This movement was a reaction to the growth of industrialism, which at that time meant ever-increasing numbers of smoky, dirty mills and factories. Its prominent members were artists and socialists who railed against how industry, and mass production in particular, churned out both dull, impersonal commodities and alienated, exploited workers. It harked back to a romanticised view of mediaeval times, when production meant individually-crafted pottery, furniture and ornaments. Emphasising how making things by hand brings us closer to what we produce, it aimed to encourage people to find pleasure again in being creative. Arts and Crafts designs were simple, light and airy, in contrast to the dominant fashion for wealthier Victorians’ homes to be cluttered, dark and stuffy. Patterns were often inspired by nature, such as in the floral motifs of William Morris’ wallpaper and William De Morgan’s pot and tile designs.

Trying to recreate both the artworks and the working practices of the movement was the premise behind BBC2’s The Victorian House Of Arts And Crafts. In this show, six craftsmen and -women spend a month living and working together, each week using traditional methods to make Arts and Crafts-inspired items for a particular room of the house.

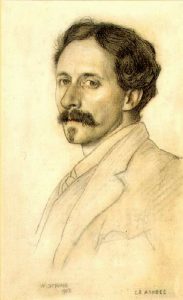

The idea of craftspeople working together as a community comes from The Guild and School of Handicraft, founded by Charles Robert Ashbee in 1888. This was a collective of workshops run with the aim of seeking ‘not only to set a higher standard of craftsmanship, but at the same time, and in so doing, to protect the status of the craftsman’. The programme aims to reconstruct such a place, where artists can bounce ideas off each other, share knowledge and experience, and find ways of working well together. Although they are already skilled in trades such as metalwork, woodwork, pottery and textiles, the show’s six participants will only be using materials, tools and techniques from the 19th century. Through the weeks their tasks include manually printing wallpaper from carved blocks and making a chair by weaving its seat from reeds and using a pole lathe to turn wood for the legs.

As well as using practical methods most of us are unfamiliar with, the Arts and Crafts movement also championed styles of work which differ from that which many of us endure. For example, rest was important to the movement, as it makes work more dignified and allows time for ideas to develop. In capitalist workplaces, where time is money, any breaks we don’t end up working through are usually just long enough to gather up enough energy to last out the rest of the day.

Unfortunately, the programme imposes tight deadlines on the artists to complete their pieces, so they have to work with more intensity and less leisurely enjoyment than the Arts and Crafts ideal. And it predictably uses another TV trope of picking a winner each week, which again seems to go against the movement’s ethos. But despite this, the participants are in the enviable position of being able to sketch their ideas while sitting in the garden before heading to a workshop to make them real. Having the opportunity to collaborate, experiment and be creative is a nourishing experience for them, echoing the movement’s belief in the therapeutic benefits of crafting by hand.

Inevitably, the programme focuses much more on art than on the movement’s political ideas. Rather than just being nostalgic for previous ways of working, the movement aimed for a new society where work could again be personal and satisfying. This doesn’t have to mean only using old techniques. As Charles Robert Ashbee said, ‘We do not reject the machine, we welcome it. But we would desire to see it mastered’. The movement’s political views were shaped particularly by John Ruskin and William Morris. Ruskin criticised the alienating nature of employment during the industrial revolution, but naively believed that society’s ills could be cured by a ‘noble’ class of philanthropic industrialists (see Socialist Standard, June 2000). Morris’ views were more imaginative and perceptive, recognising that the drudgery and exploitation of employment will remain as long as employment itself exists. His vision of the future, detailed in News From Nowhere (1890) is of a world where work is pleasurable and voluntary, as it would be if services and industry were owned and democratically run by the community as a whole. The Arts and Crafts movement remains relevant today, not just for anyone who wants to design and print their own wallpaper, but for anyone who wants a better way of living and working. The Victorian House Of Arts And Crafts was a welcome reminder of a movement which isn’t just stuck in the past.

MIKE FOSTER

AWG87427 Portrait of Charles Robert Ashbee (1863-1942) 1903 (charcoal and chalk) by Strang, William (1859-1921)

charcoal and coloured chalk on paper

© The Art Workers’ Guild Trustees Limited, London, UK

Scottish, out of copyright