The First World War and its Aftermath

At 11 am on 11 November 1918 Germany signed an armistice which ended four years of unremitting carnage. From 28 July 1914 to 11 November, over 9 million soldiers and 6 million civilians perished. The First World War is sometimes seen as an historical accident triggered by the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand. Yet from the nineteenth century onwards growing rivalries between the major capitalist powers created tensions that were bound to erupt into war.

Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71 led to the unification of Germany in 1871. The new German state then entered into an alliance with Austria-Hungary and Russia, known as the League of the Three Emperors, to contain French power. Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 and increasing Russian influence in the Balkans brought this alliance to an end. Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy then formed the Triple Alliance. To counteract this France entered into an alliance with Russia. Britain later joined France and Russia to form the Triple Entente.

Germany, since unification, had become a major economic and industrial power. Its rulers sought to compete with other major powers in world markets and seek colonies that would be sources of raw materials. To achieve this, they sought to expand their military capacity and, therefore, they proceeded to build up their navy. This inevitably led to rivalry with Britain in the control of global sea routes. Germany, Russia, France and Italy increased the size of their standing armies.

Instability arose in the Balkans as competing powers vied with each other to grab the spoils from the declining Ottoman Empire. Austria-Hungary earned the enmity of Russia and Serbia when it formally annexed the former Ottoman province of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Germany also had a strategic interest in the region. The route of the proposed Berlin-Constantinople railway would travel through Vienna and Belgrade, and therefore Germany would require some control or influence over Serbia. This would bring conflict with Russia.

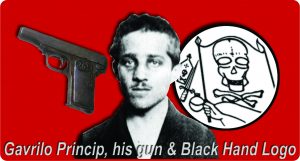

Austria-Hungary’s rulers used the occasion of the Archduke’s assassination to bring Serbia, which they suspected of promoting pan Slavic nationalism in Bosnia-Herzegovina, to heel. They delivered an ultimatum that they calculated would be rejected. Serbia accepted most of the conditions, but had reservations on others. Thereupon, they declared war on Serbia with the backing of their German ally. The Russian leaders retaliated by mobilising their forces, arguing that it was their duty to protect their fellow Slavs. But their real fear was that an Austrian victory would result in further Austrian and German encroachment of the Balkans, which would threaten to undermine their trade through the Bosphorus Straits.

The German rulers in turn demanded that Russia demobilise its forces, whereupon Russia refused and they declared war on her. A couple of days later Germany declared war on Russia’s ally, France. In order to avoid the highly fortified border with France, the German leaders decided to move their forces through Belgium. When the Belgian government refused free passage, the German military launched an invasion. Ostensibly the United Kingdom was committed by the Treaty of London 1839 to defend Belgium, and this was the reason given for declaring war on Germany. However, the British rulers main concern was the safeguarding of their trade routes to their empire, and followed a policy of ‘splendid isolation’, whereby Britain would intervene only in European affairs when there was a shift in the balance of power between the competing nations to their disadvantage. The German invasion of Belgium was deemed to be such a moment. The British government also drew on workers from the Dominions and Empire – India, Canada, Australia, New Zealand — to fight for them.

Bribery was used to entice other countries into the War. Rumania was promised Hungarian territory if they joined the ‘allied powers’ — Britain and France. Bulgaria preferred the offer from Germany, that it could have Macedonia, and so joined them. Italy was promised the Austrian regions of South Tyrol and Trieste and Northern Dalmatia by the allied powers. Italy turned her back on her former allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary, and joined the latter. Japan also joined the allied powers in the hope of acquiring Germany’s Chinese possessions.

In 1917, in a bid to end the war quickly, German forces intensified their blockade of Britain’s ports, which had been a source of friction with the United States for some time, and resumed attacks on shipping. Many American ships were sunk with a great loss of life. This, along with a telegram from the German Foreign Minister requesting support from the Mexicans in exchange for assistance in retaking US territory lost in the Mexican-American War, prompted the US government to declare war on Germany on 6 April 1917. Also, US capitalists made money out of providing financial loans to Britain and France and therefore saw it as in their economic interests to support the allied powers.

Workers did the fighting

When the capitalists of different nations fall out and go to war, they don’t normally do the fighting themselves, but get their respective working classes to do it for them. This requires an appeal to patriotism and jingoism, whereby politicians toured the country whipping up enthusiasm for the war. One successful orator was Horatio Bottomley, the so-called People’s Tribune but in fact a discredited bankrupt before the war. For all his efforts in bringing in recruits, he managed to rake in £78,000 which he spent on racehorses, women and champagne. For those young male workers who were of military age and not seduced by the clarion call to arms, young women were employed to stick white feathers on them.

The capitalists and their politicians did not garner support on their own. They had the backing of the so-called ‘workers representatives’, the Labour and Social Democratic parties, which abandoned their proclaimed commitment to the international working class and rallied behind the war efforts of their respective ruling classes. The German Social Democratic representatives in the Reichstag gave a spurious ‘Marxist’ justification for voting for war credits. A victorious Germany, they argued, would overthrow the backward Tsarist regime and capitalism would develop rapidly in Russia. Expansion in industrial production and the growth of the Russian working class would speedily create the conditions for the establishment of socialism. Trade unions showed their support by co-operating with the employers to ensure maximum production and the curtailing of any strike action. The suffragettes suspended their campaign and joined the war effort. However, there was opposition to the war from Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Sylvia Pankhurst and of course, the Socialist Party.

The capitalist class couldn’t rely on jingoist appeals alone, they needed high ideals as well. The British capitalist class claimed to be fighting for ‘the liberty of small nations’. Although this noble ideal seemingly applied to Belgium, curiously it did not apply to Britain’s colonies, certainly not in the case of Ireland, where the Easter rising in 1916 was ruthlessly suppressed. Another great ideal was ‘to make the world safe for democracy’. Oddly, censorship and restriction of war reporting was required for this one. Many would consider the Russian Tsar to be a strange bedfellow.

It would seem that it is not enough for the capitalist class that their workers were facing the bullets and bombs on the battle fronts, for they appeared to be dissatisfied with the workers’ performance on the home front. In the UK, many blamed the munitions workers for the shortages of shells needed for the war effort, that they were too busy boozing in the pubs. Restriction in pub hours were introduced which survived until the 1990s.

Discontent

From 1916, with increasing hardship and seemingly no end in sight to the war, many workers became disillusioned and there were grumblings about this being a businessman’s war. Strikes, protests and riots erupted. The situation in Russia was particularly dire, where peasants were taken off the land to fight on the front line, resulting in acute food shortages in the cities. This was exacerbated by poor communication infrastructure and corruption. Food riots ensued and mass desertions from the army took place. Workers councils emerged in the cities and organised strikes. In March 2017, the Tsar was forced to abdicate and a provisional government headed by Kerensky took his place. However, they attempted to keep Russia in the war, which only increased the discontent and their power was challenged by the Petrograd Workers Council. The German leaders saw an opportunity to take Russia out of the war. They allowed Lenin to travel through Germany in a sealed train to Russia. Once there, Lenin was able to gain support for the Bolsheviks in the Workers Councils. In November 1917, the Kerensky government was overthrown by an uprising led by the Bolsheviks. Not long afterwards, they negotiated a peace treaty with Germany at Brest Litovsk.

Now that Russia was out of the war, the German military could reinforce their forces on the Western front. Although this gave Germany an added advantage, they were still unable to deliver the knockout blow to their opponents. However, the working class discontent that brought down the Tsarist regime was also being visited on Germany. On 29 October 1918, a mutiny by sailors sparked a general workers and soldiers uprising which finally forced the German government to seek an armistice which was signed on 11 November 1918. The Kaiser abdicated on 28th November 1918.

Aside from mass human slaughter, what was the legacy of the war? It could be seen as the ultimate triumph of capitalism, as the vestiges of the feudalistic empires were swept away. The Austrian-Hungary Empire collapsed and metamorphosed into separate capitalist nation states. The Ottoman Empire disintegrated and the French and British ruling classes carved up its territories among themselves. Germany became a modern capitalist state under the rule of the Social Democratic Party. Russia evolved into an authoritarian state capitalist country. The Third International was launched during the Russian civil war in 1919 to support the Bolshevik regime and superseded the Second International which was dissolved in 1916. It became a mouthpiece of the Bolshevik regime and promoted the idea that communism equates with state capitalism and that it can only be brought about by violent revolution led by a vanguard party. This served to confuse workers as to what socialism really is and has played a part in holding back the genuine socialist movement.

With working class men being sent to the front, more women had to be brought into the munitions factories and offices to keep production going. They remained a part of the workforce after the war ended.

The phrase ‘The war to end all wars’ must be one of the sardonic statements of all times. Far from ending wars, the First World War sowed the seeds for further conflicts. The punitive measures of the Versailles Peace Treaty helped foster a sense of grievance, a feeling that Germany had been stabbed in the back. German nationalists, including the Nazis, exploited this for their own ends. Furthermore, the heavy reparations led to economic instability, such as the hyperinflation of 1923, which provided the fertile soil for aggressive nationalists like the Nazis to flourish. The increasing hostility between the Western Powers and the Bolshevik regime presaged the Cold War, which came to dominate the twentieth century. The League of Nations was set up to prevent further wars, but was powerless to do so, as it could not deal with the underlying cause — competition between capitalist powers for world markets and sources for raw materials. Wars are inevitable within capitalism.

OLIVER BOND