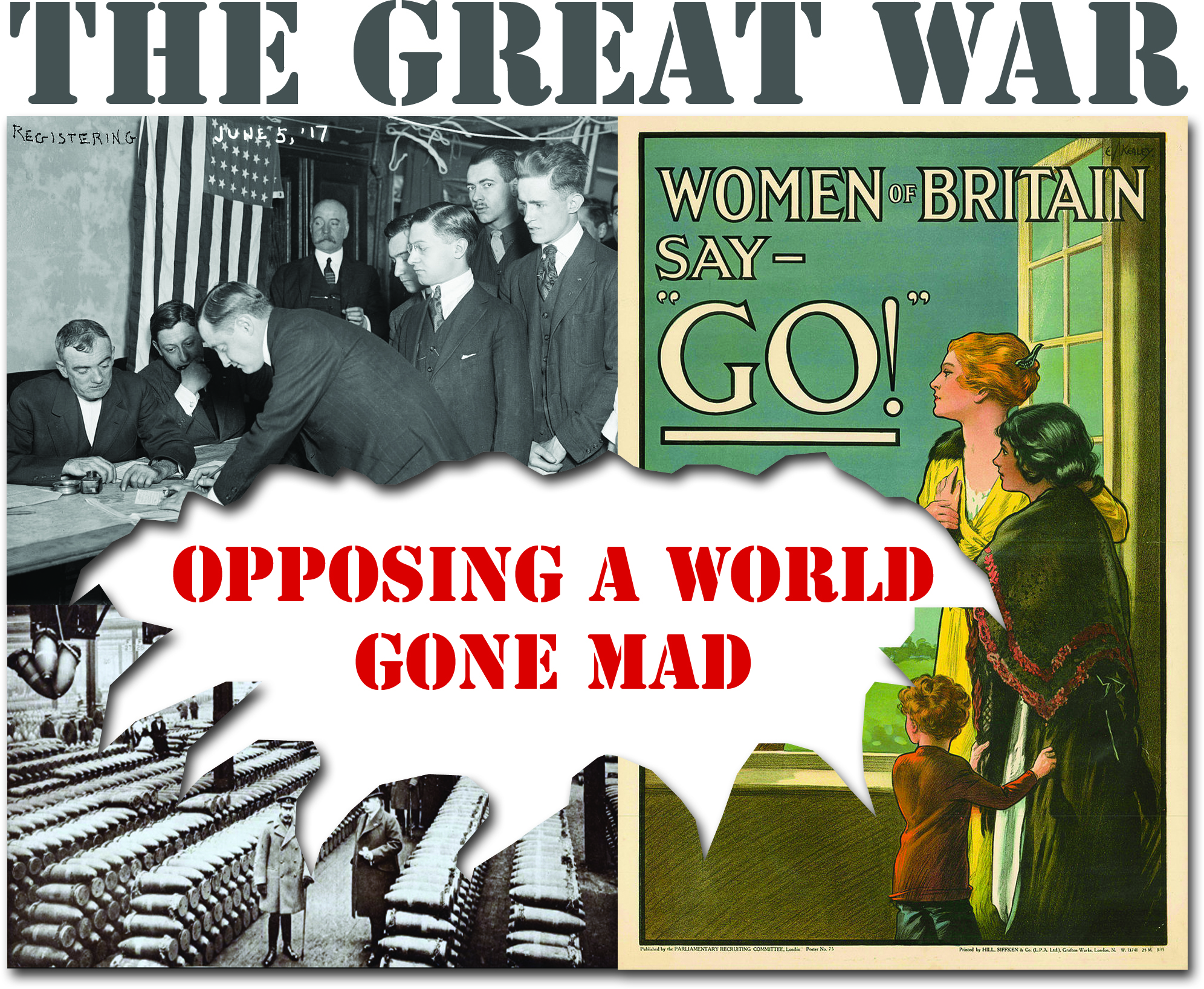

The Great War – Opposing ‘A World Gone Mad’

The Socialist Party contends that there are only two classes in present-day society. Firstly, the working class majority who collectively produce the wealth of society but who, in order to live, have to sell their ability to work for a wage or a salary. Second, the capitalist class who are the small minority who accumulate profit through economic exploitation of the working class. This situation leads to an inevitable conflict of interests and the generation of social and economic problems that cannot be solved within the present social arrangements. Commodity production – production for sale with a view to profit — leads to conflict between producers over access to markets and sources of raw materials, and for the control of trade routes and spheres of influence. From time to time this clash of interests breaks out in armed conflict. To the Socialist Party, ‘capitalism and war are inseparable. There can be no capitalism without conflicts of economic interest’ (War and the Working Class, 1936).

Within a year of its founding the Socialist Party had published an article putting its view on war:

‘I do not think it will be questioned by any socialist that it is his duty to oppose the wars of the ruling class of one nation with the ruling class of another, and refuse to participate in them’ (Socialist Standard, August 1905).

Before the mass slaughter of the First World War the Socialist Party argued that, because wars were the outcome of economic conflicts between the capitalists of the various nations, it was illogical to attempt to abolish war while the economic conflicts remained. International congresses at Copenhagen and elsewhere to ensure ‘universal disarmament’ were doomed to failure. It was clear that:

‘… the “anti-war campaign”, as such, is, from the working class standpoint, absurd. Just as the class struggle cannot be abolished save by abolishing classes, so it is impossible for capitalist nations to get rid of the grim spectre of war, for Capitalism presupposes economic conflicts which must finally be fought out with the aid of the armed forces of the State ‘ (Socialist Standard, August 1910).

The view that capitalism causes war was not held exclusively by the Socialist Party. Other parties said much the same thing and, like the Socialist Party, called for the international solidarity of the working class. However, when the war broke out in 1914 their nationalism proved a stronger force than their socialism.

To its disgust, but not to its surprise, the Socialist Party saw workers and their leaders line up behind their respective governments. Labour leaders such as Hardie, Macdonald and Lansbury assured the government that ‘…the head office of the Party, its entire machinery, are to be placed at the disposal of the Government in their recruiting campaign.’

The Socialist Party angrily denounced the war as none of the workers’ business. It was a war of capitalist interests in which ‘…the workers’ interests are not bound up in the struggle for markets wherein their masters may dispose of the wealth they have stolen from them (the workers), but in the struggle to end the system under which they are robbed… The Socialist Party of Great Britain… declaring that no interests are at stake justifying the shedding of a single drop of working class blood, enters its emphatic protest against the brutal and bloody butchery of our brothers in this and other lands…

‘Having no quarrel with the working class of any country, we extend to our fellow workers of all lands the expression of our good will and Socialist fraternity, and pledge ourselves to work for the overthrow of capitalism and the triumph of Socialism.’

In common with most political parties the Socialist Party carried on a vigorous programme of indoor and outdoor propaganda meetings. From street corners and open spaces Party speakers on platforms propounded the socialist case against war. There survives in the Party archive a bound minute book recording outdoor meetings held in North London. One entry reads:

‘September 20th. Saturday. Speaker J. M. Wray. Chair Sullivan. Time 8.30 to 10.30. Audience about 200. Opposition by Grainger of Daily Herald League supported by several members of B.S.P. in the audience with design of raising prejudice against the SPGB and so of breaking up the meeting. Disorderly meeting.’

Audience size seems to have fluctuated between 100 and 250. The meetings in August 1914 increased in size and the entry ‘Many questions mainly about the war. Good meeting’ occurs a number of times. On Sunday August 30 Wray again addressed an audience this time of around 800:

‘Many questions mainly about the war… Hostility shown by the audience so soon as the speaker began to reply to the opposition and the police closed the meeting leaving Party members to get away with the platform amongst the hostile audience that had closed around it and damaged it one side of the steps torn away and lost thus rendering the platform useless for further propaganda meetings.’

It says a great deal for the character, optimism and bravery of these early members that they could face hostile audiences week after week. Undeterred the branch repaired the platform and were by the end of the week again holding meetings. At a meeting held on October 11 the speaker replied to questions about the war when ‘On the speaker replying to the opposition the audience started the National Anthem and the raising of cheers’ and the meeting had to be abandoned. By early November the initial flush of war fever had apparently calmed down. On November 8 (a Sunday) a crowd of about 500 were reported as an ‘Orderly meeting despite of [sic] hostile element’.

On a Sunday in mid September one Hyde Park meeting was the subject of a concerted attack. The organiser reported:

‘…There was a determined attack made to smash up the meeting. Just as Elliot was closing the meeting the police intervened and told him to close down. As he did not close down as quick as they wished they arrested him. Elliott was charged [deleted] however, charged with insulting the British armies and fined 30/-. The crowd numbered over a thousand and the organised opposition attempted at the conclusion of the meeting to smash [the] platform but only succeeded in doing a little damage to it.’

Some branches reacted to the threat of physical attack by banding together to continue open air meetings sometimes at new venues. In West Ham three branches got together to hold a meeting in Stratford Grove, an area not previously covered by the Party and its limited resources. It was possibly chosen to avoid marauding gangs of jingoists who were well aware of all the regular meeting places where anti-war sentiments might find expression.

Other branches had better luck. The secretary of East London branch reported that they had abandoned a meeting at Victoria Park after an obviously sympathetic park keeper had informed him ‘…that there were eight plain clothes men present for the purpose of arresting the Speaker and the Chairman as soon as the meeting started.’ It would appear that some propaganda meetings were having some effect and it is likely that the Party’s informant had listened to the speakers over a period of time, and was at least unwilling to see its views suppressed.

But speakers did not have to oppose the war from the platform to get into trouble. A man named Baggett reported that he had been arrested and ‘bound over in the surety of £50 to keep off the platform for six months… remarks complained of had reference to Lord Roberts circular [regarding the supply of prostitutes to the British Army in India].’

In 1914 speakers had not only the government and their fellow workers to contend with. Opposition to the war and objection to military service in defence of one’s employers’ interests could incur the wrath of employers – imprisonment was not the only hardship resulting from espousing unpopular views. An early member of the Party could recall a comrade being arrested in Leicester and being jailed for a week. Phoning his employer on his release, in the hope of fobbing him off with a plausible excuse, he discovered that ‘…one of his fellow clerks had obligingly pinned up a report of his case in the manager’s office’.

In view of increasing hostility, and the fact that a number of branches had ceased to hold meetings on account of the difficult situation, the Executive Committee had to consider the suspension of outdoor propaganda activity. Every effort had been made to maintain outdoor propaganda meetings but the

‘…brutality of crowds made drunk with patriotism. The prohibitions by the authorities, and the series of police prosecutions of our speakers, compelled the rank and file of the Socialist Party to put an end to the fruitless sacrifices of their spokesmen by stopping outdoor propaganda.’

What decided the matter was the issue by the Government of stringent Defence of the Realm Regulations outlawing the uttering of statements likely to cause disaffection. The decision appears to have been a difficult one as the minutes record that it was taken after a discussion lasting about two hours. The Party at a special meeting held to discuss the situation ratified the decision. There was clearly a small number within the Party opposed to this course of action and willing to ‘tough it out’ but a motion approving of the EC decision was carried by a fairly substantial majority of 75 – 9.

Explaining that ‘…our object was not to bid defiance to a world gone mad, but to place the fact that in this country the Socialist position was faithfully maintained by the Socialists’, the Party continued as best it could. Male members, under tremendous social and economic pressures, took what measures they could to avoid being called up.

How did the Party react when members were arrested, fined or thrown out of work? It must be remembered that in 1914 state welfare provisions were primitive and being put out of work for propagating its message needed more backing than mere expression of sympathy if they were to carry on. The vast majority of members were working men.

It is heartening to read how the Party treated what were in society’s view vile miscreants. A. L. Cox reported to the EC that he had been arrested in Nottingham and charged with ‘using seditious language and inciting people to riot’. He had been taken to the Guildhall followed by a hooting crowd of about 3,000, which must have been frightening. What is interesting in this instance is that Cox was bound over in the sum of £50 – an extraordinary sum for an ordinary working man with more than a hint of vindictiveness about it. Cox was lucky. The sum had been in part under-written by a member of the BSP who had witnessed the arrest and who had provided the bail. At the hearing he stated ‘…that he opposed the view of Cox and believed he could be a Socialist and still have a country to defend.’ The EC wrote to thank the man. They also paid the twelve shillings and sixpence [62.5p] court costs and guaranteed the £50 surety.

Some idea of the hand-to-mouth existence of at least some of the members is shown by the fact that Cox reported the following week that he had lost his job on account of his arrest and had been unable to gain another. After paying for the present week’s lodgings he said he would be practically penniless. He was advanced £1 by the EC and branches were invited to make voluntary subscriptions to a fund set up to assist the EC in this matter. This brought to light another member in economic difficulties. C. Elliott, a hot water fitter, produced a letter of dismissal from his employer who had given him the sack and stopped two day’s pay. Elliott had turned up to work on Monday and told his mate who was in charge of the job that he had to go to appear in court following an arrest for opposing war. His mate said he could not get on with the job on his own and would accompany him to court. He did so but got drunk on the way. The following day Elliott alone turned up for work and could only manage to work until lunch time when he notified the general foreman. His employer got wind of the matter when the absent mate ‘gave him away to defend his own conduct in absenting himself.’ He, too, was given £1.

Neither of the men took advantage of the Party as they reported soon after that they had found employment and no longer required assistance although it would have been quite easy to do so in the absence of any way their behaviour could have been monitored.

Conscription into the Armed Forces was a distinct possibility for Party members. When voluntary recruits began to fall in number in 1915 the government turned to the expedient of compulsion to make up the shortfall. Provision was made in the Military Services Acts for the possibility of gaining exemption on the grounds of conscience. This was a provision inserted into the Bill as a sop to the Liberals, some of whom still held to voluntarist and non-interventionist principles. Prime Minister Asquith was in a political crisis and to ensure Liberal support for the passage of the Bill the provision was made with the intention of it applying to persons holding religious views which forbade the taking of human life. The passage in the Bill was badly drafted and caused the authorities no end of trouble.

Socialist Party members – all atheists – could clearly not avail themselves of the terms of the Act. In a study of the workings of conscription one author has pointed out that ‘…it was rare to find an objection that came within the definition of ‘political’ (John Rae, Conscience and Politics: The British Government and the Conscientious Objector to Military Service 1916-1919). At the end of the war the No-Conscription Fellowship published an analysis of 1,191 ‘socialist’ objectors it had particulars for and Rae is sure that this is as accurate as it is possible to be. However, it is possible that the NCF list failed to include the dozen or so objectors from the Socialist Party as the party distanced itself from that organisation refusing to have anything to do with ‘…yet another element of confusion… introduced to divert the attention of the workers from the true service of humanity.’ (Socialist Standard, May 1916), adding that while the socialist worthy of the name ‘…has the deepest conscientious objection in its most real sense to laying waste the earth and murdering men … given the occasion to do so usefully in the furtherance of the real interests of humanity he would count the sacrifice of his own life as justified.’

The Tribunals set up to adjudicate on applications for exemption from military service tended to reject political objections as not being conscientious objections within the meaning of the Act. No record exists, as far as we can tell, of a successful application from a Socialist Party member.

GWYNN THOMAS