Hype and Hypocrisy – the Magna Carta

The good burghers of the borough of Runnymede are getting excited, and Surrey county council is thrilled to bits, because on 15 June 2015 they will be celebrating the 800th anniversary of the sealing of the Magna Carta. A committee and an advisory board has been set up. Members of these bodies range from Trevor Philips, the chairman of the Equal Opportunity Commission, to Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr. who, according to the website magnacarta800th.com, is a ‘Magna Carta private owner’. Nearby Royal Holloway College is preparing quite an array of events, courses and a Smartphone app to mark the anniversary.

The strapline for the celebrations? ‘Commemorating 800 years of democracy’. Imagine, democracy for 800 years, encompassing the evisceration of John Ball after the Peasants’ Revolt in the second century of ‘democratic’ England, the shooting of leveller Robert Lockyer by Cromwell in 1649, and the hanging of 12 year-old Abraham Charlston for Luddite activity in 1812. Democracy?

Clearly not democracy. So what are Surrey Council, Runnymede Borough, Royal Holloway and any number of other organisations celebrating exactly?

King John, known as Lackland (king of England from 1199-1216) had had many disagreements with his richer subjects. Things came to a head in London on Sunday, 17 May 1215 when, whilst many people were in church, the City gates were opened to the rebel landowners by sympathetic rich Londoners. With the capital full of his opponents and too difficult to take by siege, the king had to negotiate. For a few weeks, a peace was brokered between representatives of Lackland and the barons; a document was put together, agreed to, and given to the spigurnels (chancery clerks responsible for sealing documents) to do their work. Copies of this document would have been distributed throughout the country, signifying this accord between the king and the barons. Peace, then, had broken out.

A few weeks later the document was made ‘null, and void of all validity forever’ by the Pope, in response to a request from the King. Nine barons and all the citizens of London were excommunicated. The civil war was back on. In response to resistance throughout the country, John’s soldiers destroyed villages, raped and thieved first in the North, and then down to East Anglia and across to Oxford. But not long afterwards, the French prince Louis, having been invited to invade by the barons, entered London in June 1216. Then on 18 October the King died from dysentery and within ten days his son Henry III was crowned. The document was given a few tweaks and reissued in November as a peace offering by the new King, but with little immediate effect.

It was only after a few more battles in the following year, including those of Lincoln and Sandwich, that peace was agreed with the Treaty of Lambeth in September 1217, and the French prince left the country with a bribe of 10 thousand marks.

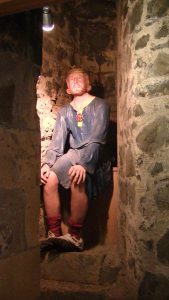

The document was issued for a third time, with further tweaks, and named ‘Magna Carta’ to distinguish it from another, smaller, issue, the Charter of the Forest. This latter document took the bits in the previous document that pertained to the forests – that is, land set aside for royals to use for hunting. It has been said that this document relates more to ordinary people than does the Magna Carta. It is true that, amongst its demands that foresters mutilate their dogs’ paws so they can’t chase deer, there is a clause that bans the removal of limbs, or life, for stealing venison. However, the document does not explicitly ban blinding, a punishment at that time. The prescribed punishment in the Charter of the Forest was a fine as heavy as can be levied according to the thief’s means, and if it could not be paid then it’s a year and a day in prison followed, if the money was still not available, by being kicked out of the country (i.e., they must ‘abjure the realm’).

These documents were regularly reissued throughout the thirteenth century, generally when the king was in need of more revenue. From starting its life as an attempt to negotiate a peace with a king, the Magna Carta seemed to turn into a way of generating taxes.

By the sixteenth century, with the Reformation and the rise of Protestantism, it is hardly surprising that a document that spoke of the rights of the (Catholic) church, and drawn up in a time in his reign when Lackland felt it expedient to submit to papal authority, would not be something to flash around. Shakespeare’s King John, for instance, does not mention the Magna Carta. When the Chief Justice, Edward Coke, suggested that the king was not above the law, James I had him dismissed, leaving him with free time to write The Institutes of the Lawes of England, which expressed his view that the Magna Carta was the basis of the common law.

In the seventeenth century, with the conflicts between parliament and king, it became fashionable, although not with the Lord Protector Cromwell, who is said to have referred to it as the ‘Magna Farta’. Levellers such as John Lilburne and Thomas Overton saw it differently, Lilburne invoking it at his trials for treason against Cromwell, quoting Coke’s Institutes, and Overton quoting the charter in An Arrow Against All Tyrants.

The leveller William Walwyn, however, had a more astute understanding. In A Remonstrance of Many Thousand Citizens he says: ‘Magna Carta itself being but a beggarly thing, containing many marks of intolerable bondage, and the laws that have been made since by parliaments have in very many particulars made our government much more oppressive and intolerable…’

Onwards into the 18th century, we see the United States considering it as a basis of their constitution and Bill of Rights. The symbol of the state of Massachusetts is a man holding a copy of the Magna Carta.

So there we have it. This is the focus of the celebration. A document that lasted in law for a few weeks in a failed attempt to prevent handbags at dawn between a king and his rich subjects, which was then split into two documents over the course of the century, and reissued whenever a thirteenth century monarch wanted more money. These bits of vellum have become a fetish that signifies democracy.

It offers protection under the law for free men. By free men, of course, it doesn’t mean the likes of us (putting gender aside for the moment). It means protection for the rich.

And it is argued that this is the first time a king has been held to account, and a limit set to his power. Yet the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells of the power of the Witan – the councils of ‘wise’ men – in pre-Norman England, and their influence on the monarchs.

Meanwhile, back in Surrey…

In woodland, close to where the Magna Carta is purported to have been sealed, lies the Runnymede Eco-Village community. It is on land occupied by the group Diggers 2012, land that has been vacant and otherwise unused since 2007 when Brunel University left the area, having sold it to a property developer, who soon afterwards was given planning permission. For around three years these hippies have been building shelters, setting up solar electricity and growing vegetables. Or, as the Daily Mail website puts it, ‘Dope-smoking anarchists sully site where King John sealed the Magna Carta with litter-strewn shanty town’ (odd that the Mail believes that the king sealed the Magna Carta with a litter-strewn shanty town and not some kind of wax on a stick).

The landowners are in the process of going to court to evict Diggers 2012.

And on 15 June there will be a celebration of democracy in Runnymede, in the presence of the Queen – a non-elected hereditary head of state, it seems, is the perfect example of these ‘800 years of democracy’. That and a thirteenth century document resulting from a hissy fit between royalty and rich men.

And perhaps freedom will be celebrated by the force of the law booting a few hippies off nearby land.

And two final commentaries written not so far apart:

‘…it is implied that here is a law which is above the King and which even he must not break. This reaffirmation of a supreme law and its expression in a general charter is the great work of Magna Carta; and this alone justifies the respect in which men have held it.’

Winston Churchill

‘… it’s through that there Magna Charter,

As were made by the Barons of old,

That in England today we can do what we like,

So long as we do what we’re told.’

(Marriott Edgar)

VINCENT JONES