Mixed Media: ‘The Arabian Nights’ & ‘William S Burroughs – All Out of Time and Into Space’

The Arabian Nights

Mary Zimmerman’s 1992 play, Arabian Nights, was recently produced at the Tricycle Theatre in London. Zimmerman was motivated by the 1991 Gulf War to dramatise The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night to portray the poetic richness of Islamic and Arabic culture. The stories are Middle Eastern and South Asian folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age (c750-1258 AD) of the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad when the Arab world was the intellectual centre of science, philosophy, poetry, commerce and agriculture. The Caliph Harun Al Rashid (Denton Chikura) is even a character in the Arabian Nights.

Mary Zimmerman’s 1992 play, Arabian Nights, was recently produced at the Tricycle Theatre in London. Zimmerman was motivated by the 1991 Gulf War to dramatise The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night to portray the poetic richness of Islamic and Arabic culture. The stories are Middle Eastern and South Asian folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age (c750-1258 AD) of the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad when the Arab world was the intellectual centre of science, philosophy, poetry, commerce and agriculture. The Caliph Harun Al Rashid (Denton Chikura) is even a character in the Arabian Nights.

The magical key line of Zimmerman’s Arabian Nights is ‘in our heads, my lord, we do contain all the images of the universe’: the play is a celebration of the imagination, the power of storytelling, and conjures up the earthy spirit of the souk and harem without recourse to the djinns and magic carpets of Aladdin or Ali Baba. The play is an ensemble piece with many accents beginning with the frame story of Persian King Shahayer and the Vizier’s daughter Scheherezade (Adura Onishile). This then opens out into stories within stories like a set of Chinese boxes which look at love, lust, shame, comedy, dreams and intellectuality.

Stories dramatised include The Jester’s Wife and Her Three Lovers, a farce of marital infidelity in which the wife hides a pastry cook, greengrocer and butcher in the lavatory. Edward Gibbon saw Islam as ‘more liberal than the laws of Moses.’ The stories of Madman and Perfect Love and The Ruined Man who Became Rich Again Through a Dream have a merchant as the central character. The Arab world was a pre-industrial merchant (bazarri) capitalist society with a market economy and monetary system. In fact Muhammad was the Prophet of the Arab merchant, and Engels identified that ‘Islam is a religion adapted to townsmen engaged in trade and industry.’

The tale of Sympathy the Learned is about a female slave who outwits the greatest intellectuals of Islamic study and can be seen as feminist in its portrayal of women. The Qur’an assumes the existence of slavery and implicitly accepts it although the Islamic world did not operate a slave system of production as in classical antiquity.

Zimmerman’s Arabian Nights evoke AL Fisher’s ‘the Arabs were poets, dreamers, fighters, traders’ and the Prophet Muhammad’s affirmation that ‘the ink of a scholar is more holy than the blood of a martyr.’

************************************************************

William S Burroughs – All Out of Time and into Space

The William S Burroughs’ All Out of Time and into Space exhibition at the October Gallery in London recently showcased his abstract expressionist paintings, drawings and talismanic art objects created in Lawrence, Kansas in the last years of the life of the writer who Mailer hailed as ‘possessed by genius.’

The William S Burroughs’ All Out of Time and into Space exhibition at the October Gallery in London recently showcased his abstract expressionist paintings, drawings and talismanic art objects created in Lawrence, Kansas in the last years of the life of the writer who Mailer hailed as ‘possessed by genius.’

Orpheus Don’t Look Back (1990) can be seen as key to his artistic creativity: Burroughs as artistic outlaw in the lineage of Villon, Rimbaud’s ‘derangement of the senses’ and Baudelaire’s soaring ‘heaven or hell’ who visits the underworld of junkies, pimps and thieves and returns, although tragically Burroughs killed Eurydice, his wife Joan, in 1951.

Self Portrait (1987) is a vague representation and recalls Burroughs’ nickname in Tangier, ‘El hombre invisible,’ when he turned his back on his bourgeois upbringing and Harvard education, advocating Hassan I Sabbah’s dictum: ‘Nothing is true, Everything is permitted,’ and his heroin addiction inspired the writing of his novel Naked Lunch published in 1959.

Death by Lethal Injection (1990) highlights Burroughs’ antipathy towards to all forms of control and authoritarianism be they political, economic, religious or sexual; his rejection of the puritan morality of bourgeois Christian civilisation and his aim to ‘make people aware of the true criminality of our times.’

Radiant Cat (1988) is a red, green and yellow dayglo painting. The Burroughs ‘weltanschauung’ was shaped by the Atomic bomb and the Cold War world of the military industrial complex. Burroughs was influenced by Spengler’s Decline of the West, Vico’s circular theory of history (Marx: ‘a whole mass of really inspired stuff ‘) and Wilhelm Reich’s Cancer Biopathy.

Untitled (1988) is spray paint and gunshots on a ‘No Trespassing’ metal sign. Burroughs opposed rapacious capitalism, detested social class and was an egalitarian with anarchistic and Emersonian individualist traits. He wrote that the Industrial Revolution with its ‘quantity and quantitative criterion’ was a ‘death trap’. He saw that international capitalism ‘always creates as many insoluble conflicts as possible and always aggravates existing conflicts.’

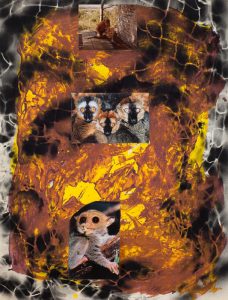

The Prison Scribe (1990) is a paint and photo collage depicting Madagascar Lemurs, highlighting his growing concern for the planet, ecology and the environment.

23 (1992) is marker pen and gunshots on watercolour paper and refers to the ’23 enigma,’ which is a key to understanding the Burroughs universe where ‘synchronicity’ unlocks the dead thermodynamic ‘hostile war universe of winners and losers.’

Burroughs wrote in Nova Express (1964): ‘Listen all you boards, governments, syndicates, nations of the world / And you powers behind what filth deals consummated in what lavatories, / To take what is not yours, / To sell out your sons forever! To sell the ground from unborn feet forever?’