Book and Film Reviews

Routine and complex labour

How to make opportunity equal: race and contributive justice. By Paul Gomberg. Blackwell, 2007.

The author of this slimmish book is a black American philosophy professor. He discusses race or racism on nearly every page, at one point making the extreme claim that “Race is class made visible and vicious.” But race is arguably not the main theme of the book. Gomberg believes that “we need to share labor, including the boring work most of us like to avoid, if everyone is to have an opportunity to develop all of their abilities.”

The good news is that the author knows something about socialism and appears to like the prospect: “Imagine a society without markets and their insistence on productive efficiency. Production may be oriented toward meeting needs, not producing whatever can be sold profitably to those with money.” And “We each benefit from the production of needed things because we each receive from the common stock.”

But the bad news is that other passages in the book reveal his confusion about what socialism means: “Market socialism does not abolish this norm [that each advances economically by their own efforts] but shifts the locus of responsibility from the individual to the worker-run firm.” And Gomberg writes about “large working-class socialist and communist parties” in Europe, parties that may be given those labels but actually support some form of capitalism.

Gomberg writes much about what he sees as the division between routine and complex labour, but leaves us unclear about what this distinction is and how it affects society. At one point he says the “division between the organization of labor tasks and the execution of those tasks is the division of society into a class society of laborers and those for whom they labor.” – in short, a society divided into workers and capitalists. But elsewhere he claims that “the division between complex and routine labor is primarily a division within the working class.”

This contradiction can be resolved only if we accept that within capitalism there are two kinds of distinction: between the owners and non-owners of capital and a distinction (perhaps better described as a gradation) between those who supply routine or complex labour, unskilled or skilled, at lower or higher rates of pay, giving orders to other workers or not doing so.

Gomberg’s front cover features a black worker sweeping the stairs. Socialists living in the capitalist world often have to do unpleasant work in oppressive conditions to get money to live. When work is done to meet the needs of people not capital there may be some horse-trading about who does what and for how long. But sociable volunteering, not monetary compulsion, will be the name of the game.

STAN PARKER

Gods, ancient and modern

UFO Religion. Inside Flying Saucer Cults and Culture. By Gregory L. Reece. IB Tauris. 2007. £11.99

Why should socialists be interested in UFOs? Well, if they really are alien spacecraft then all humans should want to know the truth about them. UFOs should really be called UAPs – unidentified aerial phenomena rather than unidentified flying objects – since there undoubtedly are unusual aerial phenomena that do need explaining, and generally can be in terms of weather balloons, reflections, optical illusions, etc. To call them “flying objects” is to beg the question.

Reece is not really interested in those he calls the “nuts and bolts” ufologists – those who seek to employ scientific methods to gather verifiable evidence that they are alien spacecraft – even if he thinks that haven’t had any success in this. His interest is those who believe in all sorts of weird and wonderful stories about them – the abductees, the contactees and those who say that aliens built the Pyramids and lived in Atlantis.

His is a book about why some people believe these things in the same way as others believe in the myths propagated by the various religions. Hence the book’s title. His style is gently mocking. For him, those who claim to have been abducted and experimented on or had sex with aliens are either hoaxers, fantasists, attention-seekers or in need of psychiatric help.

It’s the “contactees” – those who claimed to have met aliens and to have come back with a message from them – who really interest him. In the 1950s and 60s the message they reported was that the visiting aliens wanted us humans to achieve world peace and harmony and to stop testing atomic bombs in the atmosphere. Those who think that aliens built the Pyramids and the like also saw aliens as higher beings trying to help us.

Reece’s conclusion is that these imagined aliens are “modern gods” with a modernised version of what the god(s) of traditional religions are said to teach. Like them, they are the creation of the human mind, a reflection of a human aspiration for a world of peace and harmony.

He is concerned, however, that, in recent years, some of these new gods have turned out to be as nasty as the old ones. He instances Scientology and the Heaven’s Gate cult, both of which preach, in a modernised form, the old anti-human dogma that our bodies are evil and that the aim of life is to prepare for our “souls” (considered by these two cults to have come from outer space) to leave them so that we can progress to a higher dimension. I hadn’t realised before that the Mormons believe that their god was originally an extra-terrestrial. One now wants to become the US President as if the present incumbent didn’t have nutty enough religious views.

ALB

Popular change

Thinking Allowed. A Manifesto for Successful Political Change in Britain and the World.

By Sarah Young. Northern Sky, PO Box 21548, Stirling FK8 1YY.

This short, 30-page pamphlet criticises capitalism for treating us as passive consumers, denying us any control of our lives. The author rejects us following any of the “revolutionary parties of the left” as a supposed way-out, precisely because they too are organised on a top-down basis and only seek passive followers, discouraging popular participation.

She sees the embryo of a popular, participatory revolutionary movement in the voluntary activities, “vocational work” (people seeking “to serve the common good by taking on jobs in education, health or other socially related work, and often on low pay”) and single issue campaigns that thousands are already engaged in.

While accepting that these show that people are capable of organising (and should organise) themselves without leaders (whether career politicians or professional revolutionaries), we have to say that she exaggerates the potential of such activities and seriously underestimates the need for any do-it-yourself revolutionary movement such as we favour too to be consciously revolutionary.

ALB

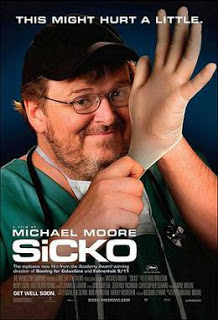

Sicko

Film written and directed by Michael Moore.

What a devastating indictment of the US health care system this film is! Fifty million Americans have no health insurance, and eighteen thousand die because of this each year. The focus of the film, however, is on those who do have such insurance — and are therefore not the most badly off — but find it of little use when they need it most.

What a devastating indictment of the US health care system this film is! Fifty million Americans have no health insurance, and eighteen thousand die because of this each year. The focus of the film, however, is on those who do have such insurance — and are therefore not the most badly off — but find it of little use when they need it most.

The insurance is with health maintenance organisations or HMOs, though they should really be called wealth maintenance organisations, as they are most concerned about the wealth of their owners and top executives. People pay for health insurance or have it provided by their employer but, when it comes to the crunch and they fall ill or have an accident, the HMO will try every trick in the book to avoid paying up. Surgical procedures may be categorised as experimental and therefore not covered, or people may be denied treatment because they did not disclose some prior medical condition or even failed to diagnose it themselves.

It is the individual cases Moore presents that give the film its impact. One child died because the HMO insisted she be treated in one of their own establishments rather than the hospital that the ambulance had taken her to. A man who had lost the tips of two fingers in an accident with a saw had to choose which one should be replaced, as he could not afford both. A sick and disoriented woman was dumped in the street by the hospital when she could not pay her bills.

Moore contrasts the American system with those in Canada, Cuba, France and the UK. He makes great play with the fact that the cashier in an NHS hospital doesn’t receive payments from patients but instead pays out, reimbursing some of them for their travel expenses. The original NHS idea of free treatment is trotted out, courtesy of Tony Benn, but disappointingly there is no discussion of the extent to which it no longer applies. Further, there’s little if any investigation of the real quality of health treatment in these countries.

All in all, though, this is a forceful attack on the idea that medical treatment should be based on considerations of profit. And just before the end comes a refreshing thought, that society should be more concerned with ‘we’ than with ‘me’

PB