Book Reviews

Contents:

* Arty capitalist

* Reformist woman

* Typical trot

* Real life poet

Supercollector: A Critique of Charles Saatchi. By Rita Hatton & John A. Walker (Ellipsis: London, 2000).

This book is frustrating to say the least, due mainly to the authors’ naïve, sub-Trotskyite standpoint. However, it still gives quite a useful overview both of Charles Saatchi as a “super-collector” and of capitalism’s ongoing relationship with art in general.

Saatchi, better known perhaps as a high-flying advertising guru, is described as someone who, as a player on the art market, “could be said to have taken control of the means of production and distribution”. This indeed seems to be the case, as his influence on contemporary art is immense. He is someone with the means to buy, show, advertise and sell art in vast quantities. It can even be said that the ludicrously named “young British art” (yBa) movement (if you can call it that) “was possibly the first movement to be created by a collector”. The way it all works is described thus:

“By seeking out new art before it became well known and expensive, Charles and Doris Saatchi were able to buy it relatively cheaply. If and when it increased in value they could re-sell it and use the profits to buy yet more new, cheap art . . . The beauty of the scheme . . . was that the increase in fame and monetary value of the art they had acquired was due in part to the very fact that they had bought it and—once they had a gallery of their own—exhibited it and memorialised it in catalogues” (p. 121).

Art buyers may be investment managers who need never actually see the artwork in question—the market value and the likelihood of it holding or increasing its value is the important thing rather than any aesthetic qualities. Works of art tend to hold their value well even in times of recession so they will always be a good punt for the anxious capitalist investor. The very fact that Saatchi has been seen to buy work by a particular artist is one way in which it is signalled that work by this individual is “valuable” and therefore worth buying. For producers of art then it became important to get noticed by a big-time buyer and reseller like Saatchi if their work was to become saleable. It became advantageous then for artists to produce work that fitted the profile of the stuff he and others had been buying—producing art entirely to meet prevailing market demand. Until that is the super-collector finds something else “new” and “sensational” which he can buy into cheap, exhibit and sell at a profit. The views of one art critic, Robert Hughes, are summarised like this:

“To meet the demand for so many shows in cities around the world … fashionable artists … are compelled to raise productivity and operate on almost an industrial scale”(p. 79).

Industrial capitalist relations between buyer and seller of labour demand industrial methods to keep up with demand for the commodity. It could be argued that this has been reflected in the sort of art that has been produced lately, especially in Britain. We hear for example of Damien Hirst’s Some Comfort Gained from the Acceptance of the Inherent Lies in Everything; a piece of work consisting of two cows sliced into 12 parts and preserved in glass and steel cases which Charles Saatchi bought for $400,000 in 1996. No doubt abattoir workers may be wondering how the “artistic process” behind this piece differs from what they have to do day-in, day-out. This is an important point as “conceptual” art like this is just that: a “concept” thought up by an artist, who will then often hire other people to actually make it.

Piles of bricks, bits of cow or heaps of electrical goods (such as Turner Prize-nominated Tomoko Takahashi’s Line-Out) are basically everyday objects which have been recycled as “art” and given a massive price tag. Essentially we all know that there is no difference between Tracy Emin’s unmade bed and our own, other than that one is labelled “conceptual art” and worth a fortune and the other is an unmade bed. This sort of stuff can be produced quickly though, which is no doubt why it has proved so popular with the art market. The most striking thing about conceptual art is probably the lack of concepts. At best the ideas that inspire much of it seem to be superficial poses, and the almost total lack of any bodies of theory or ideology behind the recent art “movements” is surely a testament to this. An interesting point this book does make is that of the links between conceptual art and advertising (the two fields with which Charles Saatchi is personally associated). Both aim at instant impact, sensation or controversy and both do so to sell a product and mask a total lack of real substance or meaning.

BM

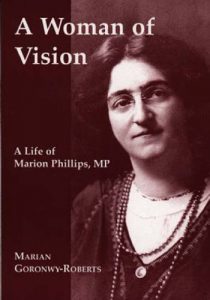

A Woman of Vision—A Life of Marion Phillips MP. By Marian Goronwy Roberts, Bridge Books, Wrexham, 2000.

A true visionary, or a crusading reformist? Both conclusions could be drawn from this biography of Marion Phillips. Roberts charts the successes and failures of this formidable Australian, who came to Britain in 1905, serving on numerous women’s committees alongside Beatrice Webb, Mrs Kier Hardie, Mrs MacDonald and Lady Frances Balfour, eventually becoming Labour MP for Sunderland in 1929, one of only nine women members of Parliament.

A true visionary, or a crusading reformist? Both conclusions could be drawn from this biography of Marion Phillips. Roberts charts the successes and failures of this formidable Australian, who came to Britain in 1905, serving on numerous women’s committees alongside Beatrice Webb, Mrs Kier Hardie, Mrs MacDonald and Lady Frances Balfour, eventually becoming Labour MP for Sunderland in 1929, one of only nine women members of Parliament.

Roberts’s admiration for Marion Phillips is obvious as she describes how, through determination and skill, Phillips placed the working woman’s perspective onto the political agenda. Unlike Mrs Pankhurst, her vision was not concentrated upon extending the franchise. As leader of the Women’s Labour League, she described its role as “keeping the Labour Party well informed of the needs of women and providing women with the means of becoming educated in political matters”. In this endeavour she gave an impetus for a quarter of a million housewives to take part in the labour movement and helped raise issues such as equality for women in the workplace, healthcare for children, the value of motherhood and an ending of the drudgery of home life. Speaking on the need for adequate bathing and washing facilities in new housing projects, she remarked: “If Labour councillors will not support us on this demand, we shall have to cry a halt on all municipal housing until we have replaced all Labour men by Labour women”.

Roberts’s admiration for Marion Phillips is obvious as she describes how, through determination and skill, Phillips placed the working woman’s perspective onto the political agenda. Unlike Mrs Pankhurst, her vision was not concentrated upon extending the franchise. As leader of the Women’s Labour League, she described its role as “keeping the Labour Party well informed of the needs of women and providing women with the means of becoming educated in political matters”. In this endeavour she gave an impetus for a quarter of a million housewives to take part in the labour movement and helped raise issues such as equality for women in the workplace, healthcare for children, the value of motherhood and an ending of the drudgery of home life. Speaking on the need for adequate bathing and washing facilities in new housing projects, she remarked: “If Labour councillors will not support us on this demand, we shall have to cry a halt on all municipal housing until we have replaced all Labour men by Labour women”.

.Phillips’s tireless efforts on behalf of working women left me a little exhausted just by the reading of it; yet it becomes the cause of my disappointment in the book. Roberts’s portrayal of Phillips concentrates far too heavily on the detail of Phillips’s political struggles on behalf of women. Or perhaps it was Marion Phillips herself who did so. There were brief episodes in the biography where Phillips broke free from her world of immediate problems and practical considerations and offered some analysis. In an article on birth control, for instance, Marion Phillips stands against the prevailing view of her reforming colleagues to limit family size, arguing that large families are only a disadvantage where economic causes make it impossible to accommodate them, arguing that birth control was becoming the doctrine of liberalism, because the Liberals did not want to make drastic changes in the distribution of wealth.

Such wider reflections were few and far between. Baby clinics, labour-saving devices, wage demands, strike committees, school meals, maternity pay . . . all piling up into an enormous reformist heap. I was overwhelmed by it, hoping Phillips or her biographer could clear a path towards a genuine vision.

Much of her work, and the work of others like her, have made it possible for women like me to be accepted as equal members of our class. As a visionary for socialism, however, Marion Phillips barely scratched the surface. None of her battles for reform could ever relieve the ultimate exploitation of women—that of wage slavery itself.

It is often difficult for socialists to evaluate successful reformers. Do we acknowledge their achievements or point to their limited ambitions? Roberts’s book is an interesting read in places, but hardly inspiring. It is up to us, as socialists, to take our vision forward. To quote Phillips in her address to the women of Hartlepool: “There is still a lot of educating to do and we are going to begin by educating ourselves”.

ANGELA DEFTY

“I know how, but I don’t know why”. By Paul Flewers.

Flewers’s pamphlet is an attempt to outline and criticise George Orwell’s political views on totalitarianism as revealed especially through 1984 and Animal Farm. As an explanation of why Orwell came to write his masterworks this is a good account. Flewers indicates the way Orwell’s experiences during the Spanish Civil War transformed his thinking, leading to a near-obsession with totalitarianism (particularly vis-à-vis Russia), and picks out his underlying motivation—the quest for “decency”.

As criticism however the work is deficient. In a nutshell, Flewers says that Orwell lacked a clear idea of how Russia became a totalitarian state because he could only observe without analysing. Since Orwell despised grand theories this is hardly surprising. But the deficiency lies not with Orwell but with Flewers. “Why was there no Lenin figure in Animal Farm?” he asks. Why overlook “the democratic features of Bolshevism?” (hack, cough) or view Lenin’s opportunism in 1917 as a “disingenuous and dishonest ruse to win support” (yessiree!). Besides the fact that Animal Farm is satire (I might just as pedantically ask “where’s Martov got to?” or “why doesn’t Makhno make a cameo?”), Orwell makes clear what his intentions were in Animal Farm: “You can’t have a revolution unless you make it for yourself.” Flewers of course denies that “any leadership will inevitably become a ruling elite once it seizes power”. As a Trot he would, wouldn’t he?

KAZ

Carnegie Hall With Tin Walls. By Fred Voss. Bloodaxe Books.

In the volume are 159 free verses depicting various facets of the daily work routine as experienced by machinists at an American aircraft components-producing factory. This is shop-floor life in the raw, as seen by a fellow machinist who prefers to remain just that, having passed up the chance to study for a PhD in English Literature.

For Voss this is real life, on the shop floor, and the men he works among are more real than those upstairs in the offices. He observes some of these men, messing with equipment, playing pranks on each other, sometimes to the point of being dangerous and near-maniacal. Voss does not excuse this outrageous behaviour or attitudes, nor does he patronise them; he is one of them. He knows that they are in a class war, and that waiting for them all, sooner or later, is being laid off, most of them without a pension.

These men could be the cream of shop-floor workers, operating, drilling, milling and capstan-type machines, which although computer-programmed, still need skill and expertise of the human touch to correct any deviance. Sometimes their raw material is a torn piece of steel which has to be honed and fashioned to within a thousandth of an inch. Voss shows that in the main they take pride in their work, although for the employed they are only there to be exploited, in the pursuit of profit.

Among the verses there are some real gems. Each one in its way is a kind of minute vignette specially when Voss adds to some of the verses a short one or two-line rider, as a wry comment on what he has just written, mostly humorous.

The verses are a denunciation of capitalism, and by satire and irony they work. Voss does not mention any union membership, or what they do to maintain any standards they have achieved. Perhaps more disappointing is the omission of any qualms that most of his employment is spent on producing parts for the military. Even so socialists can get something out of these verses.

WFM