The Birth of Labourism

The Labour Party is claiming that it was formed a hundred years ago this month. Actually it did not come into existence until after the 1906 General Election when a separate parliamentary group, with its own officers and whips, was constituted.

The Labour Party is claiming that it was formed a hundred years ago this month. Actually it did not come into existence until after the 1906 General Election when a separate parliamentary group, with its own officers and whips, was constituted.

What happened a hundred years ago, at a meeting in London on 27 February 1900, was the establishment of the Labour Representation Committee. This was a body, made up of representatives of a number of trade unions and of three political bodies (the Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation, and the Fabian Society), with the aim of securing “Labour” representation in the House of Commons so that a parliamentary “Labour Party” could be formed.

The meeting had been called by the TUC as a result of a resolution carried at its congress the previous September. It was an expression of what Lenin (right, for once) called “trade union consciousness, i.e., the conviction that it is necessary to combine in unions, fight the employers and strive to compel the government to pass labour legislation, etc” (Lenin’s mistake was to argue that, left to themselves, workers could not evolve beyond such a trade union consciousness.)

Various motions were put before the conference, the one which was carried being:

“That this Conference is in favour of establishing a distinct Labour Group in Parliament who shall have their own whips and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to co-operate with any party which, for the time being, may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interest of labour, and be equally ready to associate themselves with any party in opposing measures having an opposite tendency . . . ”

The SDF, which was an organisation which sought to model itself on the continental Social Democratic parties which were committed to the class struggle, socialism and Marxism (and of which most Socialists in Britain were then still members), tried to commit the new organisation to socialism and the class struggle, but not even Keir Hardie’s ILP supported them. In fact, Hardie always explicitly repudiated the class struggle.

The LRC didn’t even pretend to stand for Socialism. The conference was chaired by a trade unionist who was also a Liberal MP, W. C. Steadman, and many of the trade unionists involved were Liberals. According to the official Conference report, one of the delegates to the Conference, John Ward, from Newcastle, declared that “they wanted to get their feet on the floor of the House of Commons, and would not be particular how they did it”, which has remained Labour policy to this day.

The LRC faced its first test later that year in the General Election in October. Only two of the candidates it endorsed were elected, Keir Hardie and a Liberal trade unionist, Richard Bell, not enough to constitute a parliamentary Labour Party. This had to wait till after the next General Election in 1906.

At the 1901 LRC conference the SDF again tried to commit the organisation to only supporting candidates who agreed (in the words of an ILP resolution) with “the creation of an Industrial Commonwealth founded upon the common ownership and democratic control of land and capital and the substitution of co-operative production for use in the place of the present method of competitive production for profit” and (the SDF’s addendum) who “recognise the class war as the basis of all working-class political action”.

Due to a procedural manoeuvre this was not even voted on, and at its own conference that year the SDF decided to withdraw from the LRC. The report of the discussion in the SDF paper Justice (10 August 1901) brings out the arguments for and against and also that those who within a few years were to break away to form the Socialist Labour Party in Scotland and the SPGB in London supported the Executive Council on this issue against the more reformist members of the SDF (Yates was to be a founder member of the SLP in 1903 and Fitzgerald of the SPGB in 1904):

The following resolution was moved by H. Quelch on behalf of the Executive Council:

“That this Conference of the SDF decides to withdraw from the Labour Representation Committee.”

He said that when we joined this Committee we hoped the trade unionists as a body would also join, and that we could do something to bring them along our way. But the bulk of the trade unions had not joined. He wished to make it quite clear there was no antagonism between us and trade unions. It was simply that we were on different lines. It would be a mistake to antagonise the unions.

Lewis (Blackburn) seconded.

Deasey (Accrington) thought it foolish to withdraw. We should stay and endeavour to permeate and capture the trade unions. J. Hunter Watts was against withdrawing, but thought our members should remain and hold a watching brief. Steer (Battersea) said the SDF had urged the working class to use the vote and he thought we should take part in the political organisation and have a say in the matter.

J. Fitzgerald (Central) on the contrary thought we might be dragged back by the trade unions. We could do more effective work when not entangled with them. W. Gee, L. E. Quelch, J.J. Kidd, Lewis and McGlasson continued the discussion.

G. Yates said they in Scotland had joined a committee formed three years ago, and they found themselves tied to a party which could preach any nostrum that came along. Our proposals were systematically voted down and intrigued off the programme. It was an experiment and they now ought to withdraw.

Leggo (Plymouth) and Lloyd having spoken, the resolution was carried by 54 to 14.

Since the leadership of the SDF (and it was a leadership) was not against the principle of independent Labour (as opposed to purely Socialist) representation it may seem strange that they should have recommended withdrawal. However, they felt that the LRC was turning out to be another front for obtaining trade union support for the Liberal Party and so was not genuinely independent Labour representation.

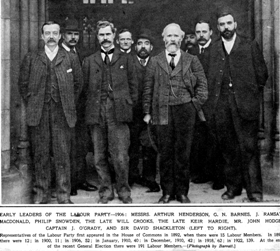

Although, twenty years later, the Labour Party did become independent—organisationally, if not in terms of ideas and perspectives—of the Liberals and in fact eventually came to replace them as the Tories’ alternate, at the time there was a great deal of truth in this, as the 1906 General Election was to show. This resulted in the return of 29 MPs endorsed by the LRC who constituted themselves into the parliamentary Labour Party. However, most of these were elected with the help of the Liberals. At that time many constituencies returned two members, so each elector there had two votes. As emerged later, Ramsay MacDonald, who was the Secretary of the LRC, had secretly negotiated a deal with Herbert Gladstone, the Liberals’ National Agent, under which in a number of these two-member constituencies there would be one Liberal and one Labour candidate and that each would recommend their supporters to give their second vote to the other

Even the ILP candidates running under the auspices of the LRC went along with this deal. “In several cases”, commented the Socialist Standard (March 1906) in a detailed analysis of the votes, “they contested double-member constituencies, and not only got in by Liberal votes, but made arrangements with the Liberals to work and vote together”. One example given was that of MacDonald himself (an ILP member) who was elected for Leicester along with a Liberal. He obtained 14,693 votes, of which 13,999 were split with the Liberals, 260 with the Tories and 426 were “plumpers” (i.e., only voted for him).

In Parliament the Labour MPs generally voted with the Liberal government. It was only after the first World War that the Labour Party became more ambitious and began to think of developing from a mere parliamentary pressure group for the unions into a party that could take over the government of British capitalism, replacing the Liberals as Tweedledum to the Tories’ Tweedledee.

In 1919 Labour adopted a new constitution allowing individuals to join directly instead of via a trade union or an affiliated political group and adopting the famous Clause IV as its ultimate aim, so committing itself to “socialism” (in reality, full-scale nationalisation or state capitalism). The Socialist Standard of the time (May 1918) was not impressed and set out a criticism of Labourism that has stood the test of time:

“The new constitution of the Labour Party does not make that party any more of a working-class party in the real sense than it has been heretofore. As has frequently been pointed out in these columns, its policy is, for the following reasons, opposed to the best interests of the working class, and calculated to hinder their emancipation.

(1) The Labour Party is not a Socialist party, and consequently is not concerned with the abolition of capitalism and wage-slavery.

(2) The time and energy of the Labour Party are spent in advocating and pleading for reforms, which cannot materially improve conditions for the working class, but which confuse the minds of the workers, leading them to expect benefits they never obtain, thus causing disappointment, disgust, and apathy.

(3) The avowed aim of the Labour Party is to get members into Parliament, in the belief that those members can legislate in the interest of the working class, whereas they are powerless to do so because they are dependent upon a capitalist party for constituencies in which to run their candidates, and the electorate of such constituencies merely vote them in because they stand for a Liberal programme and policy.

(4) By claiming to have a Socialist objective the Labour Party perpetuate the false notion that Socialism will be established, not as the result of an organised and conscious effort of the working class, but by a series of political reforms concurred in by the capitalist class.

(5) The Labour Party deny the class struggle: the antagonism between the working class and the capitalist class. Recognition of this antagonism is, quite obviously, the fundamental principle which forms the basis of a genuine working-class, or Socialist party.”

ADAM BUICK