TV Review: Away from it all

As the market economy has developed into the globalised and highly productive beast it now is, so the ostensibly “non-productive” industries have grown. Not just money-changing and paper-bashing but the service industries and leisure. Workers in advanced capitalist states like Britain are now more likely to be directly employed in banking than building and in movement of people than mining of commodities. Just as virtually every university in the land has developed a huge department concerned with Business Studies, Marketing and Accountancy, so now no forward-looking university is without its Leisure Management courses. In recognition of this phenomenon, the type of workers who are very often the product of the latter have been the focus of two recent series on BBC 1—Hotel and Holiday Reps.

These fly-on-the-wall documentaries appear to have been an undeniable success for the BBC. The first, set in Liverpool’s exclusive Adelphi Hotel, has proved hugely popular with viewers and the second series about the exploits of a group of holiday representatives abroad has not been far behind. Both series should be watched carefully by any workers seeking excitement and escape from the humdrum and ordinary in the shape of the capitalist “leisure provision” industry.

Anyone who has spent time at Liverpool’s Adelphi is more likely than not to remember it with a degree of affection. Typical of the big city hotels which grew up earlier this century, it has retained an air of grandeur long lost by most of its competitors. Now just slightly frayed at the edges it still carries the reputation of luxury craved by others. It was and remains an hotel of extravagance in a city populated by the downtrodden and wretched, an hotel where the massive and ornate chandeliers in the Tea Room stand in stark and utter contrast to the bare light bulbs and broken windows of some of Britain’s worst slum housing less than 100 yards away.

But the BBC series has not essentially been about the hotel at all—its structure, its nature or its services. It has been about the poor bastards who have to work there. The very first episode, about Grand National day earlier this year when the IRA disrupted the proceedings and thereby inundated the Adelphi with those looking for overnight accommodation, was as good an illustration as is needed of the plight of those who work for Britannia Hotels.

Get a move on

It was on this day that many of its staff worked an eighteen-hour shift—’’all  hands to the deck”. Customers were charged £100 for the privilege of sleeping on a mattress on the floor in one of the function rooms and the last few genuine hotel rooms to be sold went to the highest bidders for astronomical amounts. Britannia must have made thousands from that one night alone. And the staff’s reward for all this effort, for the hassle encountered from the inevitably disgruntled customers, and for the bullying and intimidation meted out by the management? A £5 bonus, minus tax.

hands to the deck”. Customers were charged £100 for the privilege of sleeping on a mattress on the floor in one of the function rooms and the last few genuine hotel rooms to be sold went to the highest bidders for astronomical amounts. Britannia must have made thousands from that one night alone. And the staff’s reward for all this effort, for the hassle encountered from the inevitably disgruntled customers, and for the bullying and intimidation meted out by the management? A £5 bonus, minus tax.

In this way the “new” economy of “new” Britain under “new” Labour reasserts its belief in traditional values. Profits first—wage and salary slaves at the back of the queue and no shoving, thank you very much.

For the holiday reps, thousands of miles away from the supposedly genteel Adelphi, things were not much better. For them the intimidation and exploitation was less obvious but no less real for all that. Just like marketing and advertising firms, travel companies are past masters at disguising reality. To a large extent, that is what they are actually about and how they make their money. It is therefore imperative that their representatives are as anodyne, unemotional and robotically “pleasant” as possible. It is another growing industry where insincerity is raised up to the level of an art form and genuine humanity is discouraged and dispensed with. The company comes first at all times and in all situations, and that translates into profit.

Travel companies like a certain type of employee. They are female, in their early 20s, usually blonde, and must have the innate ability to hold an antiseptic smile at all moments. Any regression from these high standards and the girls are out. It also helps if they can memorise large tracts of meaningless text which they are required to regurgitate to tourists at “welcome” meetings several times a day. They do, of course, have the advantage of doing this in balmy Lanzarote rather than cold and windy Liverpool but in every other respect they are no better off. The lure of a glamorous life abroad is soon put into perspective by the regimentation of their daily existence and £100 per week wages.

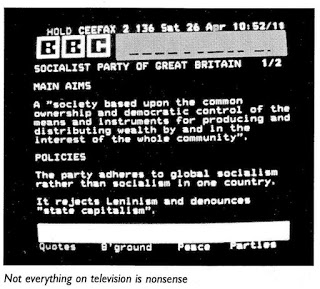

In making such apparently cynical comments as these your reviewer has the privilege of first-hand knowledge of both Lanzarote reps and the Liverpool Adelphi staff, but more importantly than either of these, a socialist perspective. Many people watching these programmes on BBC 1 will not have any of these advantages but the testament to both series is that after watching them most are unlikely to think of the leisure industry in quite the same way as they did before. If nothing else, they will at least be better informed about the methodologies of the relatively small group of people who own the tourism industry and of the stultifying existence of many of the workers who make their profits for them. And an awakening of public knowledge about that is certainly no bad thing.

Dave Perrin