The Last Word: And so to bed

I am in the middle of the tormenting exercise of buying a bed. I am, to use the vernacular of Capitalese, “in the market for a bed”. I need a bed, so I have to buy it.

You might think that everyone is entitled to something as simple as a decent bed. After all, as the salespeople never cease to remind punters “you spend almost half your life in bed. so it pays to get yourself a good one”. No, a bed is not an entitlement. It is a commodity. You want it; you buy it. Can’t afford it? Sleep on the floor.The economic rules are really quite simple.

Just how many people have no decent bed to sleep on has never been quantified. It is not an issue for the philanthropists who worry about how many millions of people are starving to death. Beds arc regarded as being something halfway between a necessity (enough food to survive healthily: denied to about a third of the world’s population) and what capitalism regards as luxury (a telly: so that you can sec pictures of people starving to death). The problem for the profit system is that the moment that anything is conceded to be a necessary entitlement there is a huge problem about who is going to pay to provide it. So, the countless children who go to bed each night on mud floors or shop doorways arc simply forgotten.

Buying a bed is a torture not very much better than being called in for questioning by the Turkish police or visiting a garden centre. In a caring world there would be counselling therapy provided for people in the process of purchasing a bed. Then again, in a caring world beds would not be for sale, but for use. Bed salespeople have the most miserable jobs, endlessly trotting out their mantra about the need for comfort—how much of life is spent in bed—the importance of a good mattress.

Most beds in most shops are complete crap, designed solely according to the measurements of the their purchasers’ poverty. No person with any real choice would sleep on the pieces of junk sold for £150 and less in the average furniture shop. Most people are unable to afford the very well designed, comfortable beds which sell for a grand or more. It is money, nothing more or less, which determines how well most people will sleep.

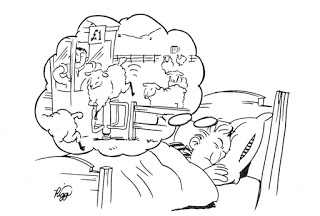

There is no doubt about it that, despite the tedium of the sales pitch, we humans do spend a staggeringly large proportion of our lives looking up at the ceiling. For a species so biologically unique in our upright stance, the amount of time that we are horizontal is quite remarkable. The horizontal position is the scene of some our most pleasurable moments. The ugly addition to the tabloid lexicon “to bed” (“BISHOP BEDS STRIPPER”) has now pushed aside anachronistic euphemisms, such as “to make love”. It is almost as if the furniture, not the human, has become the object of lust. (What was that the man said about “commodity fetishism?)

Beds are now sold as if they are sports cars (which in turn are sold as if they are penis extensions). Not long into the recently encountered experience of bed-buying I was introduced to what is a ridiculously called “The Kingsize Bed”. Precisely what size of bed does a king need-bigger or smaller than a farmer or a hospital porter or a computer programmer? One assumes that Henry VIII required reinforced springs; that George III needed straps attached to the side: that the heir apparent needs a visitor’s book attached to the headboard. What about a Serfsize bed or a Prolesize one—or, why not be really honest, and have a range called “Cheapsize” beds.There are beds on sale in Harrods which cost more than a terraced house in Burnley. If you can afford one it’s called “freedom of the market”. If you’re living in a terraced house in Burnley and you have three kids sharing a room and sleeping on worn-out mattresses with springs sticking through it’s called a sick way of running society.

I now know the bed market pretty well. I know that the more you pay the better you will sleep. I know that futons are for fitness freaks, masochists and extremely poor people. I know that I am so exhausted of bed-hunting that I could now sleep on a park bench if it could be fitted with an extra-large sleeping bag and an overhead light for reading.

William Morris was right—as usual. Furniture, to be worth making, should be both useful and beautiful. Beds, chairs, wardrobes, bookcases, desks . . . all that a decent society need do is produce them for use and make sure that they are the best and most beautiful which the variety of human desires might require. But the buying and selling system thrives upon the indecency of filthy commerce, turning everything (even a good night’s sleep) into the basis of a fast buck.

Steve Coleman