Was Labour ever Socialist?

Now that Blair has openly proclaimed the Labour Party to be just another party seeking to run capitalism many on the Left are looking back with nostalgia to the days when Labour was supposedly a Party with a radical programme for abolishing capitalism and establishing socialism . . .

All too common nowadays is the sigh from disillusioned Labour Party supporters and ex-members (Scargill included) that the Labour Party is “no longer” socialist. Some claim Labour stood for socialism in 1945, while others will say Labour’s socialist credentials can be traced back to 1918 and the adoption of the old Clause Four. And there are those who believe that Labour was bent on socialism at its foundation in 1906.

Let us, therefore, look to the foundation of the Labour Party—the Labour Representation Committee as it was in 1900—to see whether socialist ideas were in circulation amongst its founding fathers.

On a depressingly cold day in late February 1900, in the Memorial Hall on Farringdon Street, London, 129 delegates gathered for a conference. They represented some 568,000 discontented, but organised workers. They had been sent by 65 trade unions, the Social Democratic Federation, the Independent Labour Party’ and the Fabian Society.

The conference was the result of a resolution passed at the TUC the previous September, a resolution moved by the Railway Servants, to “bring into being an alliance of the trade unions and new socialist societies which would be strong enough to fight the political battles of the working classes in parliament”.

Pseudo-Marxist SDF

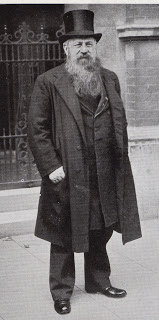

Of the four groups represented, the SDF claimed to be the true standard bearer of socialism. Their claims, though, were largely spurious. H. M. Hyndman, the party leader, was well-known for his autocratic rule. Marx had found him totally obnoxious and had made every attempt to avoid him. Engels saw Hyndman as having “ossified Marxism into a dogma”.

Hyndman was not only a sad victim of self-aggrandisement, he was also over-optimistic, carrying about his person at all times a list of names for a revolutionary cabinet—himself as the big boss—should the glorious day come.

Marx believed that the task of overthrowing capitalism had to be the sole responsibility of the working class itself, acting in its own interests and, consequently, in the interests of the entire human race. Hyndman, however, could not accept this. He held an arrogant contempt for the intelligence of the working class believing, like Lenin, that the workers had to be led by professional revolutionaries like himself.

Hyndman was, in reality, an opportunist, a romantic interested only in the prestige and power a working class victory would afford him. He had shown his true colours during the 1885 General Election. Then, the SDF had been low on funds, and Hyndman and friends thought it would be a good idea to enter into negotiations with the Conservative Party, working on their fears of a Liberal victory, and persuading them to invest in a plan to split the Liberal vote by financing the campaigns of two SDF candidates. The Tories agreed, and when news of the scam got out it caused such an uproar among workers that the two SDF candidates, John Williams and John Fielding, secured only 59 votes between them.

There were some socialists in the SDF but they were opposed to the concept of a “Labour party” and left in 1903 and 1904, some to set up the Socialist Party which has published this journal ever since.

In any event, the SDF soon withdrew from the Labour Representation Committee.

Elitist Fabians

Another group represented at that February conference, and who also shared Hyndman’s opportunism and contempt for the working class while claiming to be “socialist”, were the Fabians.

Engels described the Fabians as a “clique . . . united only by their fear of the threatening rule of the workers and doing all in their power to avert the danger”—a statement that in hindsight appears mild.

The Fabians had some 861 members in 1900, of whom only one was an actual wage slave, albeit a retired wage slave. Sidney Webb was right to famously declare that “we personally belong to the ruling class”. These sentiments were taken a stage further by his wife, Beatrice, who despaired of the working class and believed that the Fabians could find “no hope from these myriad of deficient minds and deformed bodies that swarm our great cities—what can we hope for but brutality, madness and crime?” Twenty years later, Beatrice was to hold the same views, seeing unions as “underbred and undertrained workmen”. For Bernard Shaw, the situation could only get worse and he thus proposed “sterilisation of the failures” in an attempt to stop the rot infecting further burdensome generations of workers—sentiments to be expressed by Winston Churchill in 1904 and Hitler some 30 years later.

Engels was quite right to detect in the Fabians a fear that a working class revolt would dislodge them from their privileged positions. Such fears had been panicking the British well-to-do since 1789. By the mid-1890s, the Fabians had become influenced by the Liberal Party, and by Joseph Chamberlain, a Tory, who believed that some kind of welfare system was essential if the propertied class wanted to survive. The Fabians argued for social services and improved conditions for workers not out of genuine altruism, but in the belief that this would help stave off unrest.

Unlike the SDF who fostered a prophecy of impending revolutionary doom, the Fabians, as Bealey puts it in his introduction to The Social and Political Thought of the Labour Party, “foresaw a peaceful, gradual change by constitutional means from capitalism, through collectivism, to socialism”. Rejecting the Marxian view that the state was a manifestation of the domination of the propertied class, the Fabians believed that the state was “a neutral apparatus that could be utilised by anyone who could legitimately become a government”. For the Fabians, though, the idea of the workers taking control through the state apparatus was anathema to everything they represented.

The Fabian idea of socialism was that of a stale run by experts and professionals like themselves, trained in the emerging modern human and emerging social sciences. They were in fact technocrats, believing that the technical administration of society should take the place of party politics. Like the other confusionists of the period, the Fabians were also oblivious to the idea that “the upsurge of popular feeling and action that alone could transform society must come from the working class themselves”, as the Labour journalist Francis Williams put it in his history of the Labour Party in 1945, Fifty Years March.

Like true opportunists it mattered not, of course, which political party took on board Fabian ideas, for they “expected by tactics of permeation and education to sell their programme to the leaders of the Conservative and Liberal parties” (Bealey, p.5). Thus, elitist in their tactics and aspirations, they were further open to the charge of being prepared to collaborate with openly capitalist parties.

Anti-class struggle ILP

The Independent Labour Party (ILP), founded in 1893, was another of the nascent working class organisations to declare themselves socialist. They had, however, “no very well defined set of ideas” other than they called for an “industrial commonwealth founded upon the socialisation of land and capital” and that they demanded workers “be given a place in the national set up” (Bealey, p.6).

Like the Fabians, they too feared a workers’ revolt would severely upset the status quo, and they warned in 1895 that should there be a workers’ revolution in Euroec “there is nothing save a narrow strip of sea betwixt us and what would then be the theatre of a great human tragedy” (quoted in Bealey, p 16).

Philip Snowden, the party’s economic expert, was of the opinion that the propertied man “could not enjoy his riches in the knowledge of the misery of the men and women and children around him . . . it is to the cultured and leisured classes that socialism, perhaps, makes its strongest appeal”.

Socialism meant, for the ILP’s leaders, that the propertied would run society in the interests of the workers, granting them just so much reform that they could be kept at bay. In return, the workers would be imbued with ideas “drawn straight from the wells of capitalism” (Bealey, p. 17). The ILP’s declared objective was “the collective and common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange”, i.e. state and municipal capitalism.

As to the socialist, or rather so-called socialist, credentials of ILP leaders Ramsay MacDonald and Keir Hardie, it should be remembered that both men joined the Labour movement not out of any deep-rooted conviction that the capitalist system must come to an end, but because they both had been rejected as Liberal candidates.

Whereas class consciousness, a realisation by workers of their objective position in the relations of production was, for Marx, a prerequisite for social revolution, for Hardie, who often stressed the common interests of worker and employer, the ILP did “not want class conscious socialists”. Hardie actually believed that the “socialist” movement was being undermined by workers fighting their capitalist employers as their class enemies. MacDonald would come to his aid, arguing that “class consciousness leads nowhere” and that the buzzword should in fact be “community consciousness”.

The New Unions

The three “socialist” societies, then, that sent delegates to the February conference, a conference that was to form the Labour Representation Committee which six years later became the Labour Party, were in fact putting a lid on working class discontent—from the outset not wanting to abolish capitalism, but to ameliorate its harsher effects.

The idea of the 1900 conference, as has already been mentioned, was the result of a resolution passed at the TUC some five months earlier. What remains significant is that the resolution was only passed by 546,000 to 434,000 votes. And it is also interesting to note that only a few years earlier the TUC had passed a resolution aimed at extricating the trade unions from “the influence of socialist adventurers”. The September 1899 resolution was, therefore, “no trumpet call to social revolution” (Williams, p.9).

In the late 1880s, the unions had enjoyed some significant victories—victories that had perhaps lulled them into a false sense of security. Most notable was the inspiring Match Girls victory at Bryant and May in 1888 which “succeeded because it mobilised behind it forces far greater than the match girls could command (public opinion)” (Williams, p. 10). Within two years, optimism had given way to pessimism, as employers, with the backing of the state, hit back at militancy with a vengeance. Between 1890 and 1892, membership of the “new unions” fell from 320,000 to 130,000. Disillusionment was further compounded when 70,000 were battered into submission in Scotland in 1894 and with the crushing of the Boot and Shoe Operatives and the Amalgamated Society of Engineers the following year.

There had been since the 1880s a growing awareness that the state was too big an opponent to be tackled by the trade union movement and that the trade unions now needed their own political voice. The Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884 had widened the franchise and it was with this in mind that George Shipton would write in Murray’s Magazine in 1890 that “when the people were unenfranchised . . . the only power left to them was the demonstration of numbers. Now, however, the workmen have votes . . . the ‘new trade unionists’ look to Governments and legislation—the old look to self-reliance”.

Among the 65 unions that sent delegates to conference there was a lot of reluctance from the older trade unions “who feared the consequence of any move that seemed to be directed at changing their own conception of a trade union as a craft organisation primarily concerned with safeguarding the interests of its workers by direct negotiation with individual employers” (Williams, p. 15).

The initial motivation behind the conference was “to secure better representation of the interests of labour in parliament”, as the 1899 resolution had stated. The “new unions” were not motivated by any socialist vision of the future. Their aspirations were economistic and immediate. For them “socialism” meant higher wages and shorter hours and a hoped-for redistribution of wealth. “They were,” as Bernard Shaw observed, “out to exploit capitalism, not to abolish it” (quoted in Bealey, p.6).

So again, any suggestion that the new trade unions, any more than the “socialist” societies, provided the early labour Party with a socialist ideology is highly dubious. In fact, by the end of the first day of the conference, the delegates had passed a resolution stating that any Labour MPs should be prepared to co-operate with the already existing capitalist parties: “That this conference is in favour of establishing a distinct labour group in parliament, who shall have their own whips and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to co-operate with any party which, for the time being, may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour” (quoted in Williams, p.24).

Furthermore, that same day, the conference elected as its chairman a Fabian, W.C. Steadman, who was “not by any means a convinced socialist. On the contrary he was himself a Lib-Lab MP . . . who in general worked and voted with the Liberal party in the House of Commons” (Williams, p.19).

The next day the conference elected a 12-man executive committee consisting of 7 trade union representatives, two from the SDF, two from the ILP and one from the Fabians. They agreed to call their new movement the Labour Representation Committee. They were not, however, to act together as a political party. If anything they were a federation of trade unionists and political organisations, each retaining their own identity. All four groups were less motivated by socialist theory than by the growing awareness that capitalism had raised the stakes. They were slowly coming to terms with the social, economic and political pattern of the times, vaguely grasping the fact that capitalism can only be tackled politically through the ballot box where workers had the power to vote for the social system they wanted. However, they only wanted political action to try to ameliorate capitalism rather than to abolish it and replace it with socialism.

John Bissett