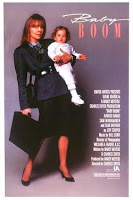

Film Review: Buying the baby

Babies, it would seem, are big business. Having first tried to sell us the glossy lifestyle of the young, upwardly mobile careerist, unencumbered by little more than a filofax, two recent films (and others are on the way) are now trying to humanise the stereotype with the addition of a baby or two.

Diane Keaton’s latest film, Baby Boom, is about a successful young businesswoman who is suddenly landed with a baby — not her own — and discovers that life a s high powered management consultant is more difficult when nappies and bottles have to be combined with brief cases and business meetings. When ultimately faced with the choice between baby and career, not surprisingly the oh-so-cute baby wins. Keaton leaves Manhattan for a dilapidated farm house in Vermont. That is in the autumn. By spring she has not only fallen in love with the local vet (Sam Shephard), but she’s also turned a recipe for apple sauce into a million dollar baby food business. A typical story of life as a single parent.

Diane Keaton’s latest film, Baby Boom, is about a successful young businesswoman who is suddenly landed with a baby — not her own — and discovers that life a s high powered management consultant is more difficult when nappies and bottles have to be combined with brief cases and business meetings. When ultimately faced with the choice between baby and career, not surprisingly the oh-so-cute baby wins. Keaton leaves Manhattan for a dilapidated farm house in Vermont. That is in the autumn. By spring she has not only fallen in love with the local vet (Sam Shephard), but she’s also turned a recipe for apple sauce into a million dollar baby food business. A typical story of life as a single parent.

Three Men and a Baby offers us essentially the same kind of story. Three  men-about-town, living in a shared apartment, have a baby dumped on them which messes up their lives in all kinds of predictable, if faintly amusing ways. But again, sentimentality will out. Despite all the complications the baby causes, they can’t part with her.

men-about-town, living in a shared apartment, have a baby dumped on them which messes up their lives in all kinds of predictable, if faintly amusing ways. But again, sentimentality will out. Despite all the complications the baby causes, they can’t part with her.

Apart from the presence of a baby, there are a couple of other features that these two films have in common. Firstly, there’s the manner in which the heroes/heroine come by the baby in the first place. In both cases the child is simply dumped upon them. In much the same way that soap operas like Dallas and Dynasty expand their cast by one of the main characters suddenly discovering that they have a child/parent/spouse that they didn’t previously know about. How can these people so carelessly lose relatives all the time? In Baby Boom this part of the story is particularly implausible. We are supposed to believe that Diane Keaton “inherits” the baby from distant cousins. The implication, I suppose, is that a woman in her position would not actually choose to have a child and so has to have one thrust upon her in order that she can discover the maternal feelings that lurk just below the surface. Why they didn’t just resort to the stork or the gooseberry bush, I don’t know. It would have been about as believable as “inheriting” a child.

Secondly, there’s the rather curious idea that, having tried to sell us the life-style that goes with being young, rich, independent, successful and so on, we should now “buy the baby” to complete the package. In other words, having been kitted out with the executive brief case, the designer clothes, the Porsche and the penthouse, the next step is to acquire the baby as a means of humanising what is otherwise seen as a soulless existence.

Buried somewhere underneath all that gooey sentimentality there’s probably a positive message of sorts, namely, that human relationships are important. But these two films are cute, not incisive. They address a tiny minority of people who have pursued a certain kind of life-style at the expense of all else. The majority of us didn’t need to be told that human relationships are important — many people in capitalism have little else of value in their lives — nor that children are simultaneously frustrating, demanding, messy and also a source of joy and fulfilment. Or maybe I’m being too generous and the truth is much more simple: that films about cute kids make money.

Janie Percy-Smith