The Decline of Coal

Coal played a great part in the development of capitalism in Britain. Wood used to be the main fuel but in the 18th century coal mining was stepped up as coal was needed for smelting iron. Many mines were in fact owned by the ironmasters. Coal was also used for steam-raising and, with the expansion of steam driven locomotives, ships and machines, in the second half of the 19th century, production increased from about 50 million tons in 1851 to over 240 million in the first decade of this century. The peak year for the British coal industry was 1913 when 287 million tons were mined, of this nearly 100 million were exported or went into bunkers for ships sailing to overseas ports. In the nineteenth century coal had no serious rival as a source of fuel and power. Coal was and still is used to raise steam for electricity generation and also in the manufacture of town gas.

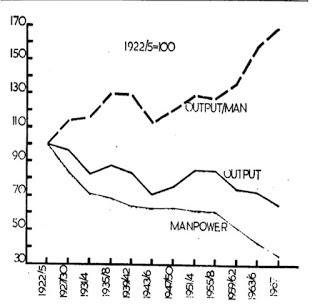

Because of its importance as a source of fuel and power for modern industry, coalmining was particularly hit by industrial depressions, as our graph shows. It also placed coalminers in a strategic position. The miners played a major role in the development of the working class movement in Britain. Their history was one of continuous struggle against rapacious mine owners, often involving bloody clashes with the military. The first working class MP’s, elected for the capitalist Liberal Party, were miners. The Miners Federation of Great Britain, set up in 1889, was at one time the largest trade union in the world. The General Strike of 1926 was called by the TUC in answer to a lock-out of miners. Although the strike was called off after nine days, the miners heroically held out for nine months before being defeated by hunger. Between the wars, and specially at the beginning of the thirties, almost the whole adult male population of many mining villages was out of work. It is probably fair to say that, as a result of their experiences and of living in their own communities, the miners reached the highest degree of industrial class consciousness of any group of workers in Britain; at least this is true of the South Wales miners.

Coalmining was an industry in whose efficiency all capitalists were interested as they wanted the cheapest energy they could get. The old owners were notoriously inefficient so that nationalisation was advocated by many besides the Labour Party and the MFGB. The Tories nationalised the coal before the war, and Labour the mines after. On vesting day, 1 January 1947, every one of the thousand collieries displayed a large notice proclaiming: THIS COLLIERY IS NOW MANAGED BY THE NATIONAL COAL BOARD ON BEHALF OF THE PEOPLE. Many miners thought that this was Socialism or at least a step toward it but it was only state capitalism. The miners remained exploited wage-workers even though nationalisation allowed an improvement in working conditions. There has been no official strike in mining since nationalisation; so-called unofficial strikes have been frequent however. The main union is the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), as the MFGB became in 1946. The NUM has rivals organising clerks in the Clerical and Administrative Workers Union (CAWU) and various underground supervisors in the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS). Management grades are in the British Association of Colliery Management (BACOM).

In the event of redundancy Polish workers shall be the first to go. They shall be transferred or dismissed wherever their continued employment at a particular pit would prevent the continued employment or re-employment of a British mine-worker who is capable of and willing to do the work on which the Polish worker is employed and who might otherwise be displaced by redundancy at that pit or at another pit.

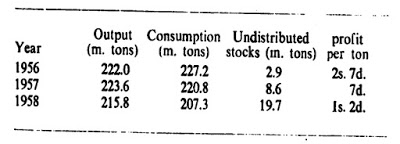

Total coal output in 1957, including that from opencast sites, was 223.6 million tons. This was 1.4 million tons more than in 1956 and the highest annual output since 1952.

Total coal output in 1958 was 215.8 million tons, including 14.3 million tons from opencast working. For the first time, the Board had to take steps to restrict production to meet a decline in demand; the years output was 7.8 million tons less than that of 1957 and was the lowest for eight years.