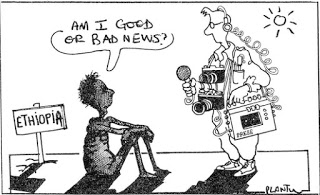

Last year five of the eight countries in the Sahel region of Africa had record  harvests. Regional production of cereals is estimated to have been 6.3 million tonnes, or 10 per cent more than in 1981, the year before the much-publicised drought and famine in the area began. Good news, you might think. Or is it?

harvests. Regional production of cereals is estimated to have been 6.3 million tonnes, or 10 per cent more than in 1981, the year before the much-publicised drought and famine in the area began. Good news, you might think. Or is it?

In a world organised to serve human needs a bumper harvest would of course be good news, but we are not living in such a world. Instead, we are living in a world where food and all other goods and services are produced for sale with a view to profit. No profit, no production is the basic rule and it is its inexorable application that leads to people dying of starvation in one part of the world while in other parts governments stockpile “surplus” food and pay farmers to take their land out of cultivation. Those who starve do so because, not having the money to buy the food they need to stay alive, they do not constitute a market from supplying which a profit can be made. It is as simple as that.

But what about food aid? Quite apart from the fact that it is often used to further the foreign policy aims of the donor governments (were voices not raised against giving food aid to Ethiopia because its government aligns itself with state capitalist Russia? And was not the rejoinder that aid should be given precisely to wean the Ethiopian government away from Russia?), the amount of food distributed in this way can never be more than marginal since it goes against the whole logic of the capitalist system. If practised on a wide scale it would amount to the economic aberration of instituting production for use in one sector (producing food for free distribution to those who need it) in a world of production for profit. Production for free distribution is of course quite logical from the point of view of human interests, but if applied under capitalism it creates problems. This is why the bumper crop in the Sahel could turn out to be bad news, as explained in a specialist publication:

When an abundant local harvest occurs it comes up against the food aid stocks of millet, maize and sorghum. This aid visible on the local markets brings about a collapse of prices. National silos, filled up with aid food, cannot accept the new harvest. The local producers then risk not finding a buyer, or if so at what price? The following year they will plant a smaller area, as already happened in Togo in 1985 following difficulties in disposing of the 1984 harvest. If in 1986 the reduction in cultivated areas were to be combined with a drought year, the situation of the Sahel would become disastrous (La Lettre de Solagral, December 1985).

In other words, in a system where food is produced for sale, giving away food free merely upsets the market and leads to a reduction in food supplies. This is quite in accordance with the logic of capitalism. In fact, so absorbed were some relief workers by a (no doubt sincere) desire to help starving areas beyond the very short term that, at the height of the Ethiopian famine, they could be found urging that limits be put on the amount of free food sent to Ethiopia. They would have preferred to see aid channelled into small-scale projects which, unlike the free distribution of food, would not have impeded the development of local production for the market.