Manifesto of the Socialist League

A hundred years ago this month the first Annual Conference of the

Socialist League, which had been founded in December 1884 as a breakaway from the Social Democratic Federation, adopted the following Manifesto.

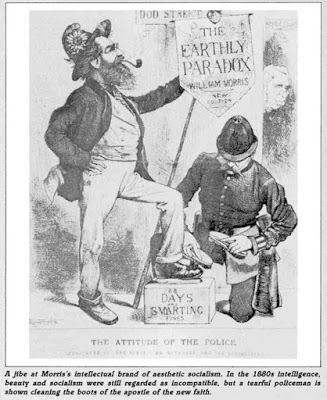

Drafted by William Morris, it went through many editions and represents the first clear statement in the English language appealing to workers to undertake an uncompromising struggle to replace “the present system of capital and wages” with a system in which “all means of production and distribution of wealth” would be “treated as the common property of all”. Apart from one or two loose phrases (which our regular readers will immediately recognise) it is still an excellent statement of the case for socialism; it is also a fine example of political English.

The Socialist League virtually disappeared in 1890. but fourteen years later another organisation, also a breakaway from the SDF, took on the task of advocating “the principles of Revolutionary International Socialism”: the Socialist Party of Great Britain.

Fellow Citizens — We come before you as a body advocating the principles of Revolutionary International Socialism; that is, we seek a change in the basis of Society — a change which would destroy the distinctions of classes and nationalities.

As the civilised world is at present constituted, there are two classes of Society — the one possessing wealth and the instruments of its production, the other producing wealth by means of those instruments but only by the leave and for the use of the possessing classes.

These two classes are necessarily in antagonism to one another. The possessing class, or non-producers, can only live as a class on the unpaid labour of the producers — the more unpaid labour they can wring out of them, the richer they will be: therefore the producing class — the workers — are driven, to strive to better themselves at the expense of the possessing class, and the conflict between the two is ceaseless. Sometimes it takes the form of open rebellion, sometimes of strikes, sometimes of mere widespread mendicancy and crime; but it is always going on in one form or other, though it may not always be obvious to the thoughtless looker-on.

We have spoken of unpaid labour: it is necessary to explain what that means. The sole possession of the producing class is the power of labour inherent in their bodies; but since, as we have already said, the rich classes possess all the instruments of labour, that is, the land, capital, and machinery, the producers or workers are forced to sell their sole possession, the power of labour, on such terms as the possessing classes will grant them.

These terms are. that after they have produced enough to keep them in working order, and enable them to beget children to take their places when they are worn out. the surplus of their product shall belong to the possessors of property, which bargain is based on the fact that every man working in a civilised community can produce more than he needs for his own sustenance.

This relation of the possessing class to the working class is the essential basis of the system of producing for a profit, on which our modern Society is founded. The way in which it works is as follows. The manufacturer produces to sell at a profit to the broker or factor, who in his turn makes a profit to the retailer, who must make his profit out of the general public, aided by various degrees of fraud and adulteration and the ignorance of the value and quality of goods to which this system has reduced the consumer.

The profit-grinding system is maintained by competition, or veiled war, not only between the conflicting classes, but also within the classes themselves: there is always war among the workers for bare subsistence, and among their masters, the employers and middle-men for the share of the profit wrung out of the workers; lastly, there is competition always, and sometimes open war, among the nations, of the civilised world for their share of the world-market. For now, indeed, all the rivalries of nations have been reduced to this one a degrading struggle for their share of the spoils of barbarous countries to be used at home for the purpose of increasing the riches of the rich and the poverty of the poor.

For, owing to the fact that goods are made primarily to sell, and only secondarily for use, labour is wasted on all hands; since the pursuit of profit compels the manufacturer competing with his fellows to force his wares on the markets by means of their cheapness, whether there is any real demand for them or not. In the words of the Communist Manifesto of 1847:

Cheap goods are their artillery for battering down Chinese walls and for overcoming the obstinate hatred entertained against foreigners by semi-civilised nations: under penalty of ruin the Bourgeoisie compel by competition the universal adoption of their system of production: they force all nations to accept what is called civilisation — to become bourgeois and thus the middle-class shapes the world after its own image.

Moreover, the whole method of distribution under this system is full of waste; for it employs whole armies of clerks, travellers, shopmen, advertisers, and what not, merely for the sake of shifting money from one person’s pocket to another’s; and this waste in production and waste in distribution, added to the maintenance of the useless lives of the possessing and non-producing class, must all be paid for out of the products of the workers, and is a ceaseless burden on their lives.

Therefore the necessary results of this so-called civilisation are only too obvious in the lives of its slaves, the working-class — in the anxiety and want of leisure amidst which they toil, in the squalor and wretchedness of those parts of our great towns where they dwell; in the degradation of their bodies, their wretched health, and the shortness of their lives; in the terrible brutality so common among them, and which is indeed but the reflection of the cynical selfishness found among the well-to-do classes, a brutality as hideous as the other; and lastly in the crowd of criminals who are as much manufactures of our commercial system as the cheap and nasty wares which are made at once for the consumption and the enslavement of the poor.

What remedy, then, do we propose for this failure of our civilisation, which is now admitted by almost all thoughtful people?

We have already shown that the workers. although they produce all the wealth of society, have no control over its production or distribution: the people, who are the only really organic part of society, are treated as a mere appendage to capital as a part of its machinery. This must be altered from the foundation: the land, the capital, the machinery, factories, workshops, stores, means of transit, mines, banking, all means of production and distribution of wealth, must be declared and treated as the common property of all. Every man will then receive the full value of his labour, without deduction for the profit of a master, and as all will have to work, and the waste now incurred by the pursuit of profit will be at an end, the amount of labour necessary for every individual to perform in order to carry on the essential work of the world will be reduced to something like two or three hours daily; so that every one will have abundant leisure for following intellectual and other pursuits congenial to his nature.

It is clear that for all these oppressed and cheated masses of workers and their masters a great change is preparing: the dominant classes are uneasy, anxious, touched in conscience even, as to the condition of those they govern; the markets of the world are being competed for with an eagerness never before known; everything points to the fact that the great commercial system is becoming unmanageable, and is slipping from the grasp of its present rulers.