Fear and hope

Workers are frightened. Scared of being put on the dole, scared of not being able to afford the rent or mortgage, scared of being beaten up for cash, scared of the terrorists’ bomb, scared of the poverty of existence on a pension, scared of the devastation which could so easily be caused by one powerful leader pressing a nuclear button. Workers would be daft not to live in fear, for we are living in fearful times under an inherently frightening social system.

Workers are frightened. Scared of being put on the dole, scared of not being able to afford the rent or mortgage, scared of being beaten up for cash, scared of the terrorists’ bomb, scared of the poverty of existence on a pension, scared of the devastation which could so easily be caused by one powerful leader pressing a nuclear button. Workers would be daft not to live in fear, for we are living in fearful times under an inherently frightening social system.

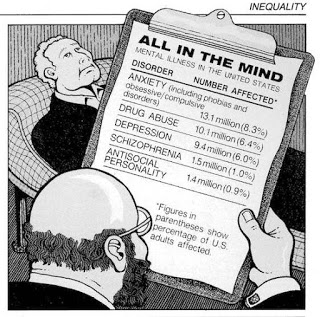

Why are millions of workers taking tranquillisers? Why are there longer queues than ever for the psychiatric hospitals, where those who cannot handle their fear-caused depression go to collapse? Why is the suicide rate in Britain so high? Why is our society facinger”>

<div class=”post-footer-line post-footer-line-1″></div>

</div> a heroin epidemic, with whole areas of deprived inner cities becoming known as “smack alley ”? Because people are happy with what capitalism is doing to them — or because we are living in a social atmosphere of overwhelming fear?

There are no soothing words capable of calming workers who are afraid. Women who cannot afford taxis are in danger every time they walk at night through streets filled with adverts exhibiting the female form as a consumable object. Capitalism, with its lying promise that workers can have access to what they want, creates the rapists just as it creates the muggers. People walking the unlit streets and estate walkways of Poverty City are in danger of being stabbed for pennies and pounds and are in danger of going home to find that someone else in poverty has broken in. We are right to fear the bomb which may be planted on the train or in the street and the store where we shop. It is not only in Belfast, but in the big stores of Oxford Street and the pubs of Birmingham or Guildford that workers understandably live in a constant state of tension. Old workers are dying in their thousands every winter and no amount of reformist talk will ease the fear of those who dread the forecast which tells them that death for the poor is once again on the weather chart. There are so many reasons to be worried that it is painfully clear why many thousands try to escape into the unreality induced by drugs and drink.

In November of last year the Sunday Times published the following report:

Large numbers of children feel anxious and helpless about the possibility of nuclear war, according to a survey (carried out by the Avon Peace Education Project, an independent organisation funded by the Joseph Rowntree Trust). Of the 561 comprehensive schoolchildren questioned, 91 per cent think they would not survive the holocaust, 30 per cent think a nuclear war is likely to happen in their lifetime and 21 per cent think one could happen at any moment. Just under half (45 per cent) say that thoughts of nuclear war actually affect how they feel about making career and marriage plans . . . One 11-year-old said: “To survive a nuclear war would be horrible. Nearly all your friends and relations would be dead. You would probably end up killing yourself”.

Adult readers skilled in self-deception may have smiled at such infantile fears. But these are not kiddies having nightmares about invented ghosts and dragons. Their fears reflect a reality which only the blinkered cannot see, and if we care for our children we will not pat them on the head and tell them to go away and play soldiers.

Under capitalism there is no escape from fear. Take bombs: let us imagine that all nuclear bombs are abolished tomorrow — about as believable as any proposed by the reformist “realists”. Would we be free from fear? No. Still there would be the constant worry that some government would recreate the nuclear bomb, for there is no security in the vicious competition of capitalism. And everyone knows that the military technology exists to create a non-nuclear holocaust just as horrific as anything predicted now. Or, on a personal level, you may be a supposedly secure worker one of the so-called middle class — with your own house, as secure a job as you can hope for, and a few thousand pounds in the bank maybe even a few shares. What happens if tomorrow morning your doctor tells you that one of your family has a disease which can only be treated if you pay for it and the cost is several thousand pounds more than your bank account contains or your few shares are worth? You could sell your house, but how long would the money of even the best-off worker last when it really comes to the crunch? How many workers can live without fearing the next problem? And even those who imagine they can — how is their supposed affluence going to save them from being blown to pieces in a war, killed as a result of environmental pollution or allowed to die of a disease which the government has not put the money into researching a cure for?

Capitalism provides no hope for the working class. But that does not mean that there is no hope. In a lecture in 1884 William Morris declared that:

Fear and Hope those are the names of the two great passions which rule the race of man. and with which revolutionists have to deal; to give hope to the many oppressed and fear to the few oppressors, that is our business; if we do the first and give hope to the many, the few must be frightened by their hope; otherwise we do not want to frighten them; it is not revenge we want for poor people, but happiness; indeed, what revenge can be taken for all the thousands of years of the sufferings of the poor?

(How We Live And How We Might Live)

Perhaps it sounds a little sweeping — even reminiscent of those miserable Christians who have come to save us all and make us happy — but the simple fact is that only socialism offers hope for the working class. For, once we have re-organised society on the basis of common ownership and democratic control of the means of living and production solely for use, the cause of our present fears will disappear. This is not to say that there will be no other problems and that nobody will have anything to fear in a socialist society; natural diseases and personal tragedies will always be around and no political revolution will eradicate all of them. But we can say with certainty that in a socialist society no man or woman need fear the enforced idleness of unemployment — or the enforced drudgery of wage slavery. Fear of war will not exist, for the property-based cause of war will be gone. Nobody will need to fear for lack of money, for in a moneyless world of free access such anxieties will be unimaginable. Instead of fear we can at last be motivated by the enormously creative power of conscious control over the social environment, out of which will come unfettered hope. We are living in cynical times and it is fashionable to expect doom. Socialists are hopeful, and we intend to turn our hope into reality.

Steve Coleman