Book Review: White Law

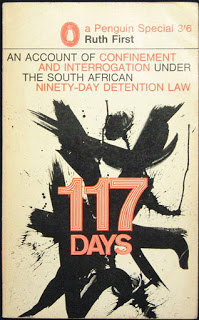

117 Days: An Account of Confinement and Interrogation under the South African 90-Day Detention Law by Ruth First (Penguin. 1982).

117 Days: An Account of Confinement and Interrogation under the South African 90-Day Detention Law by Ruth First (Penguin. 1982).

Originally published in 1965, 117 Days has been reissued following Ruth First’s death last year in Maputo, Mozambique. She was killed by a letter bomb which, according to Ronald Segal in his preface to this new edition, was issued by “those guards of the South African regime . . . not swaggering in their uniforms but in a seemingly safe package which had been treated to blow her apart”. Ruth First was well known to the South African authorities before her imprisonment in 1963 because she had published accounts of the use of forced labour on the farms of the Transvaal and exposed the conditions under which migrant labourers worked in the gold mines of South Africa

First was arrested under the General Law Amendment Act of 1963. A person could be arrested without warrant if they were suspected of having committed or intending to commit any offence under the Suppression of Communism Act (1950), or if suspected of sabotage or in possession of any information relating to such an offence. The person could be detained for a period not in excess of ninety days or until that person, in the opinion of the Commissioner of the South African Police, had satisfactorily answered all questions during interrogation. The act became known as the “90-Day Law”.

Ruth First was arrested under suspicion without warrant and without facing trial. After her initial arrest she was released just within the period of ninety days, only to be immediately rearrested. She spent a total of 117 days in solitary confinement undergoing repeated interrogation. She had already been banned “from writing, from compiling any material for publication, from entering newspaper premises . . . I had worked for five publications and each had, in turn, been banned or driven out of existence by the Nationalist Government”. She had in her home, at the time of her arrest, a copy of Fighting Talk, a publication she had edited for nine years and possession of which was punishable by imprisonment for a minimum of one year.

First was originally imprisoned in Marshall Square. The conditions under which she was detained are described in horrific detail and with touches of irony:

I, a prisoner held under top security conditions, was forbidden books, visitors, contact with any other prisoner; but like any white South African Madam I sat in bed each morning, and Africans did the cleaning for the “missus”.

Even the bucket of hot water for washing, a concession for “Ninety-Dayers”. was brought to the cell by the African inmates until a shower was finally installed in the prison during her two months at Marshall Square. She was then moved to Pretoria Central Prison for the next twenty-eight days before being returned to Marshall Square.

Although never charged. First was aware that the Security Police knew of the magazine at her home and that she had attended meetings at Rivonia with Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and others. Interrogation took a number of forms and ranged from threats such as “this is the first period of ninety days; there can be another after that, and yet another” to cajolements such as “we’re not holding you, you’re holding yourself. You have the key to your release. Answer our questions, tell us what we want to know , and you will turn the key in the door”.

Ruth First’s portrait of prison is not limited to her experiences but covers the experiences of many others including Looksmart Solwandle Ngudle, who committed suicide during imprisonment, and Isaac Tlale who revealed evidence concerning his own torture during “90-Days” imprisonment and of the torture of Ngudle:

Looksmart by his death and Tlale by his courage had lifted the lid for the first time on the systematic resort to torture of Ninety-Day detainees by the Security Branch.

First focuses attention on the South African prison system’s concern with vengeance. She herself attempted suicide during her second period of detention. Her conclusion is that “these amateurs in political sleuthing who seized books because they had ‘black’ or ‘red’ in the title had developed into sophisticated sadistic mind-breakers in the matter of a few years”. This is a savage indictment of the South African policies of apartheid and the suppression of any ideas conflicting with the status quo in that country.

Philip Bentley