Book Review: A bad case of Flew

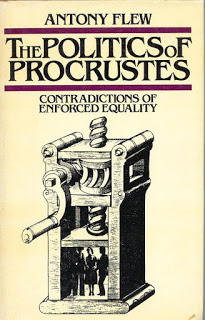

Anthony Flew, Professor of Philosophy at Reading University, is a committed opponent of the case for human equality. Last September he debated with the SPGB on the argument that “equality is just a socialist myth”. His latest book. The Politics of Procrustes, is a readable account of the confused and occasionally vicious views of a defender of capitalism.

Anthony Flew, Professor of Philosophy at Reading University, is a committed opponent of the case for human equality. Last September he debated with the SPGB on the argument that “equality is just a socialist myth”. His latest book. The Politics of Procrustes, is a readable account of the confused and occasionally vicious views of a defender of capitalism.

Like most anti-socialists, Flew fails to give any clear definition of “socialism”. Despite his claim that he aims “to clear up some of the confusion to be found around and about the notion of socialism” (Chapter One) he soon arrives at the typically confused definition of socialism as “state ownership and direction of — in the hallowed words of the original Clause IV of the Labour Party — all the means of production. distribution and exchange”. He proceeds to make the outrageous claim — rejected even by most Labour Party supporters — that the Labour Party “has been for more than sixty years, and still is, both in theory and in practice, socialist”. With Professors of Philosophy like Flew “clearing up the confusion” about the meaning of socialism in such a manner, we may well repeat the question of Karl Marx: “Who is going to educate the educators?”.

Socialism does not mean state control and the Labour Party has never stood for the establishment of socialism. The basic features of the capitalist system are — minority class ownership and control of the means of wealth production and distribution: wage slavery for the propertyless majority; the production of wealth as commodities to be sold on the market with a view to profit. Those who fail to recognise these basic features of the system will fail to see through the spurious claim that state capitalism—either as proposed by the Labour Party or as practised in Russia and China—is socialism. Two opposite systems cannot be defined by identical characteristics; capitalism and socialism are mutually exclusive.

Only by absurdly distorting the real nature of capitalism can Flew and his colleagues in the misnamed Freedom Association, assert that capitalism provides us all with freedom. Flew informs his readers that “It is the friends . . . of the market generally who are in truth the friends of individual liberty.” For Flew, the buying and selling system of the market is the finest example of social Freedom:

. . . trade is a reciprocal relationship. If I am trading with you it follows that you are trading with me. Trade is also, for both parties, necessarily voluntary . . . So, if any possible advantage of trade to the trader could be gained only at the expense of some corresponding disadvantage to his trading partner, it would appear that in any commercial exchange at least one party must be either a fool, a masochist or a gambler (p. 150).

Flew is right when he states that buyers and sellers start out in a position of reciprocity. For example, a worker selling his labour power needs a wage or salary in order to live and a capitalist buying labour power needs the worker’s mental and physical energies in order to produce profits enabling him to live. In this sense, both classes go into the market place upon equal terms, unlike in previous slave or serf societies where the producer was legally tied to the owner of the means of production. To this extent, then, we can speak of freedom. But Flew is wrong when he states that the contract between buyer and seller is “necessarily voluntary”.

The truth of the matter is that the working class is compelled to sell its labour power because it has nothing else to sell. (Such is the definition of a worker.) Legally, workers are free not to work (although it is illegal to remain on the dole for long without seriously seeking employment—and begging is illegal), but in reality it is impossible for a worker to survive for long without selling his mental and physical energies to an employer. The wage slaves who are regularly poured out of the schools and universities into the factories and offices are not entering into a voluntary condition of dependence upon wages or salaries—nobody asked them whether they would prefer to be wage slaves or capitalists: they are the compulsory victims of capitalist exploitation.

Flew argues that workers would only enter into an arrangement of exploitation, one where the capitalists’ gain results from their disadvantage, if they are fools, masochists or gamblers. The assumption is that such exploitative transactions only occur occasionally. In fact, such exploitation is the hallmark of the production of profit under capitalism. When the capitalist buys the worker’s labour power he pays a price for it which fluctuates around its value, or what is needed for the worker to subsist and to reproduce himself. But labour power is only employed if it can produce values over and above its own value. For example, if a capitalist buys a worker’s labour power for a wage of £80 a week and invests £30 in machinery and raw materials, the worker must produce commodities which will sell at more than the investment or £110 before a profit can be made.

The employer will only take on the worker if he can predict that surplus value will be produced. If the worker produces goods valuing £150, then the capitalist has made £40 profit. This unearned income is made for the capitalist at the direct expense of the worker. Workers cannot insist that they will only work long enough to reproduce their own value, for the very essence of the arrangement is that labour power will be exploited for profit. If the workers do not like the arrangement there is nothing they can do to opt out of it, for they are wage slaves dependent on obtaining money in order to survive and the capitalist class own and control the productive and distributive machinery. If the workers realise that they are being deprived of the fruits of their labour and decide to appropriate for themselves some or all of the surplus value they will be called thieves and locked up in a prison. The capitalists are not known as thieves (by those who seek to legitimise this theft) because their theft is legalised. As Flew says, workers who put up with this daily exploitation would seem to be “fools” or “masochists” do to so for long.

Having examined the real nature of the profit system, we may now return to the Professor’s ignorance of the meaning of socialism. It does not mean that instead of private capitalists exploiting the working class, a state bureaucracy will do it. Workers who are exploited by the government are no less exploited than any others. Socialism means the common ownership and democratic control of the productive and distributive machinery. In a socialist society everyone, without distinction of age. race or sex will own and control the social wealth. Instead of wage slavery, people will contribute to society as much as they are able to. Instead of buying and selling, people will take according to their needs. Instead of production for sale on the market with a view to profit, all production will be solely for human use. Socialism will be a system of society where the spurious freedom of the market place (the liberty of the capitalists to take liberties with the working class) will be replaced by free access. In a society of co-operative, conscious human control of the earth and all its resources there will be no exploiters and exploited, robbers and robbed—we will at last be free, equal social beings.

Steve Coleman