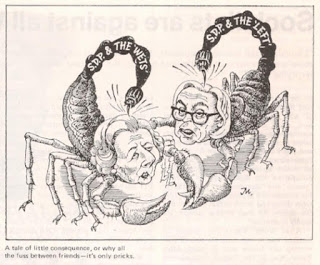

Political Notes: Stand Again

Is panic the only motivator of Labour MPs agog at the polls (for what they are worth) which say that the Social Democratic (sic) Party would sweep to victory at an early general election? Could conscience also be gnawing away at them?

Such questions spring to mind when reading of the anguished demands from the Labour benches that any MP who joins the SDP should at once resign from Parliament and fight a by-election under their new colours.

These MPs, runs the argument, were elected by voters who (except in the case of B. F., or Brocklebank-Fowler) supported the Labour Party programme. It they have now changed their political views, those electors arc disenfranchised; the honest, democratic thing to do is to give the constituents the chance to have their say on the change.

This indignation would he more impressive if the House of Commons were not full of people who spend their time in Parliament imposing policies very different from those they were elected on. Yet none of them has so far resigned on the issue.

Labour MPs are especially guilty in this. How many of them, for example, told the electors in 1974 that they stood for cuts in living standards, medical services, for breaking strikes, for making the rich richer and the poor poorer? And how many of them eased a tortured conscience, when their government carried out these policies, by asking the voters what they thought in a by-election?

If MPs really behaved as those anxious Labour members are now demanding, the House of Commons would be pretty well empty. The bars, the dining rooms, the lobbies would no longer resound with the jolly banter of capitalism’s legislators. The House is said to be the most exclusive club in the world but, as any political careerist will agree, you can take exclusivity too far.

Crooked aim

“It is the thinking person’s party” trumpeted a recent convert to the Social Democratic (sic) Party. Unkindly critics might have commented that it doesn’t take that much brain to wield an Access card but let that pass, after all, the SDP are only trying to prove that they are alive and clicking in the age of the credit card. Vote now — pay later might be their motto.

Well how does the “thinking person” like his politics? Before he or she fills in that credit card number on the application to join the SDP, he/she is invited to agree that they “share our (SDP) aims”. Now that sounds perfectly straight forward except that the SDP so far doesn’t have any aims. Indeed, according to the Guardian (10/4/81) the hairy SDP leader William Rodgers “. . . insisted that there was still a long way to go before the infant SDP has even a constitution, let alone an agreed political programme.”

It would take the thinking person — not to say one who could read and write — only a minute or so to run through the advertisement which included the application form on which they had to confess their support for SDP aims to realise that there was absolutely no hint there of what SDP aims might be.

The very most the T.P. would find would be vague promises like standing for “. . . a new future”, which may be a strong contender for the Waffler of the Week award but is not a political policy worth — or even capable of — being discussed.

Of course traditionalists who relished the empty thunder of Churchill, the oiled assurances of Macmillan, the sweeping platitudes of Wilson, will welcome the SDP as a talented contributor to the art of political half-think (their stuff does not yet merit the description of doublethink).

But the SDP claims to be new, to be breaking the mould of traditional British politics. So far their supporters remain starry eyed and hopeful in their delusion but they must be aware that using a credit card is only a postponement of reality; eventually the bill has to be paid

Reagan responding

With a bullet in his lung Ronald Reagan gave out. unknowingly, some discomforting lessons for all exponents of the political assassination policy.

Anyone who thought that getting Reagan out of the way would modify his policies could not have been reassured by the fact that as a result the American working class were almost subjected to a period under the rule of Alexander Haig. The ex-Vietnam general is by reputation a harder line, farther right wing hawk than Reagan himself.

As he recovered, wise-cracking, from his wound, Reagan was borne up on a popular wave of sympathy and support. Most observers agreed that if he had been fighting the presidential election right then his victory would have been even more emphatic than it was last November.

The majority Reagan got then would not have melted away or solidified around an opponent, if the assassination attempt had succeeded. An example of this was when Johnson swept Goldwater almost to oblivion in 1964. In that campaign the Democrats coldly exploited the emotional response to John Kennedy’s killing which, far from damaging their chances, must have contributed to their crushing win.

Political murder is an established method with “extremists’ of both “left” and “right” wings but there is no reason to think that it acts against the ideas represented by the victim. The evidence in the cases of Kennedy and the attempt on Reagan (although the signs are that neither was for political ends) is that the murder of a politician induces sympathy and not hostility.

The properly effective way of dealing with an opposing theory is to prove, if possible, that it is at variance with reality. Such a method, although it has little appeal for the political romantics with guns, is the only way in which we shall build the political consciousness needed to establish a new society.