At one stage the French Minister of Agriculture floated the idea of amending the 1976 law so as to legalise the injection of natural hormones but, in view of the hostile response, quickly dropped the idea. And now, under the proposed Common Market regulation, all hormones, whether natural or artificial, are to be banned. In Britain, incidentally, certain hormones were allowed to be administered under licence; according to the press, they have not been used on veal, only on beef. So perhaps the Roast Beef of Old England hasn’t always been as traditional as claimed. Hormones have also been used in beef in France, but the Minister of Agriculture intervened to tone down an article in another consumer magazine which highlighted this. He evidently felt that, with pressure being brought to bear on him by irate calf-raisers threatened with ruin by the consumer boycott (consumption and prices of veal really did fall off dramatically), he could well do without a similar pressure from beef-producers.

the livestock farmers are forced to cheat since it is often the difference in weight arising from the administration of hormones that represents their margin of profit (Republicain Lorrain, 13 August 1980).

Another organisation explained that some farmers broke the law because “the low level of profit does not always allow the heavy investments to be amortised” (Ouest-France, 12 September 1980).

These claims were confirmed by a Working Party of scientists set up by the Ministry of Agriculture which concluded that, if cheating went on, this was because anabolisants generally, with or without hormones, “are useful to the profitability of stock-farms” (Republicain Lorrain, 19 September 1980). The same issue of this paper quoted “professional circles” for figures which showed that the use of anabolisants (what some weight-lifters and shot-putters use to put on weight) without hormones allowed a stock-farmer to increase his production by 5 per cent; of anabolisants with natural hormones to increase it by 5-10 per cent and with artificial hormones by 10-15 per cent. “In these circumstances”, the paper concluded, “it is logical that the stock-farmer who is in any case going to take the risk of cheating should choose the most profitable product”. Which also happens to be the most dangerous to human health.

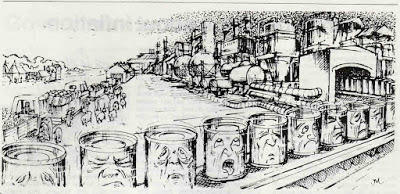

Although many of the farmers involved did so just to get a living income, big profits were still to be made out of the use of hormones in veal production. The hormone’s themselves— including DES (only its use, not its production, was illegal) —had to be produced industrially by a complicated chemical process and it was the big drug firms which were involved in this. They encouraged the practice, sending out their pushers to try to convince farmers to use their products and chemists and vets to prescribe and administer them.

The real lesson of this episode of Veau aux hormones is not that there should be stricter laws governing the quality of meat on sale, but that we live under an economic and social system which makes such laws necessary. The fall in consumption and prices was undoubtedly the key factor which got the French government to say that in future it would enforce the law banning hormones and to press for a similar ban at Common Market level. But, quite apart from the fact that it remains to be seen whether the French (and other) governments will in fact make available the number of inspectors and laboratories that will be needed to enforce the ban, the same sort of battle will have to be fought over and over again, with consumers organisations always on the defensive, reacting to some new way round the law which some capitalist firm has thought up. Already in fact it is being suggested that the drug companies, which have made millions out of the hormones in question, will now switch to manufacturing other anabolisant drugs which will have the same effect on the growth of calves. These, apparently, have not been pushed till now since hormones were cheaper. In a few years time then the fight will still be on for drug-free meat.

So-called “consumer protection” laws, in any event, are passed in the general interest of the capitalist class as a whole and not to protect that nebulous entity, the “consumer”. Most consumers of food are wage and salary earners and, if they are being poisoned by the activities of a section of the capitalist class, then it is the other sections who will in the end be harmed since the quality of the labour power which they consume, and for which they pay the worker a wage or salary, will be diminished. It is because a reasonably healthy workforce is in the interests of employers generally that consumer protection laws are passed. The consumer who is being protected is the consumer of labour power.

The very need for the capitalist class to have to pass such laws against their own excesses is in itself a condemnation of the capitalist system. For what sort of economic system is it that has to threaten to use the force of the state machine to try to ensure that one group does not poison the rest of society? If production was for use and not for sale, as it will be in socialism, on the basis of the common ownership and democratic control of the means of production, such a problem just could not arise. It is quite inconceivable that anybody would even think of adopting a practice which was known to be a risk to human beings. Production being carried on solely to satisfy human needs, nothing would be produced and no processes would be used that might in any way be a threat to human health and well-being.