Book review: The Face of Capitalism

Lonrho — Portrait of a Multinational by S. Cronjé, M. Ling and G. Cronjé. (Pelican)

Lonrho — Portrait of a Multinational by S. Cronjé, M. Ling and G. Cronjé. (Pelican)

The book attempts to document the growth and activities of the Lonrho Company over the last decade or so. Lonrho has more than 500 subsidiary and associate companies and the range of its overall activities is huge. The ownership of mines, cattle farms, railways, newspapers, pipelines, sugar refineries and commercial properties are some. This makes the writing of a coherent account a difficult task and added to this the authors appear to have derived a great deal of their information from the mass media. Their Notes section at the end of the book quotes articles from several hundred periodicals and newspapers as sources, and their Introduction states that they found it largely impossible to obtain information direct from the highly secretive Lonrho board. For these reasons the book never attains more than that level which interests newspapers, particularly the financial pages.

The result is a complicated record of years of wheeling and dealing which Lonrho and its associates have engaged in, both with other companies and with political leaders — notably in Africa. The increase in profits which Lonrho had shown, from £14.44m in 1969 to £46.44m in 1974 for example, is explained in terms of astute deals, successful takeovers, clever share manoeuvres and so on. There are vague references to the output of various subsidiaries increasing, or of others expanding significantly and becoming more profitable, but the credit for this is placed firmly on the Lonrho board’s foresight, and on occasion, their luck. The chief executive director, “Tiny” Rowland, is given particular prominence and much of the company’s success is attributed to his ability to make personal contacts with men in high places, who in turn gave Lonrho preferential treatment. They quote Roland’s own statement:

When I’m abroad, I am entertained and do business with Rulers, Presidents and Prime Ministers, who entertain me and look after me. (p. 242)

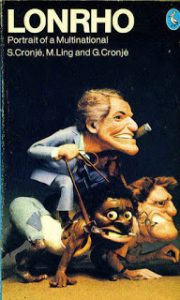

Virtually no attention is focussed on the fact that while Rowland and his board members are busy being entertained, they, and their hosts are supported in their privileged position by thousands of property-less workers. One idea that this is the case is given on the cover design where a cigar-smoking model of Rowland is seen astride a black man and a white man who have both been harnessed. Rowland is holding the reins. When the book was published recently he was annoyed at the inference.

The issue which was provoked by the more hypocritical shareholders over the low wages paid to workers in Lonhro’s South African mines is dealt with briefly. The official Lonrho line was deliberately evasive; though the parent company owned almost 97 per cent. of the offending mining companies, fixing of wage levels at the mines was a matter for the local puppet company, Lonrho South Africa Ltd. The book notes that “South Africa was not the only place where Lonrho paid low wages” and gives the example of Sri Lanka (Ceylon) which in 1974 was the subject of a War on Want pamphlet stating that severe cases of malnutrition were common among its workers. Lonrho’s personnel manager “admitted that conditions were a matter for ‘concern, but said that the company was making hardly any profit in Sri Lanka’ ” (p. 86).

The authors repeat the suggestion that Lonrho has been engaged in “sanctions busting” through subsidiaries in Rhodesia — a suggestion leading to the resignation of Angus Ogilvy, and claim that the Rhodesian and South African interests have proved embarrassing to Lonrho when they have been courting “black” African governments — they give several instances — for franchises, concessions and contracts, because of an alleged ideological difference. Again the Company line was ingenious if nothing else; should they sell up these interests the! new owners might prove to be simply a gang of ruthless capitalist exploiters — unlike Lonrho themselves! In this connection the authors casually refer to African states “with a commitment to some form of socialism” (p. 248) who are going to pose what the book concludes is the issue, “whether capitalism is going to have an acceptable face in Africa at all”. The suggestion is that the emerging black leaders who wine and dine men like Mr. Rowland and his “respectable” cohorts have something else in mind, although they offer no evidence for this.

With the virtual absence of Socialist understanding among African workers, and the determined action by the governments of rival nation states to exploit greater masses of the African population in order to accumulate capital for the ruling minorities, it is a naive suggestion to make.

Alan D’Arcy