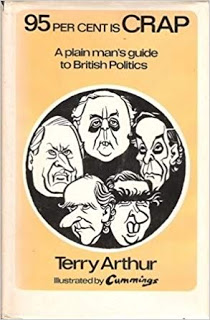

95 per Cent is Crap: A Plain Man’s Guide to British Politics, by Terry Arthur. Liberation Books Ltd., £3.50.

95 per Cent is Crap: A Plain Man’s Guide to British Politics, by Terry Arthur. Liberation Books Ltd., £3.50.

If nothing else, this is a handy compendium of extracts nonsensical, contradictory and self-revealing from politicians and “leading authorities”, with derisive comments made from the stance of “the man in the street”.

No partisanship is shown — the subject-matter comes more or less equally from Labour and the Conservatives, with the Liberals, Communists and National Front in tow. The author writes in a bluff saloon-bar style like that of the title (we hardly need to be told he is a Rugby player): “bloody” abounds. This is an obvious Christmas present for the person who thinks all politicians are on the make.

Anyone else, including serious students of Association football, would have reservations. Terry Arthur’s advice to all is, at every election, to put a big cross right across the ballot paper, “preferably with a short rude message . . . If you feel dissatisfaction, register it, rather than help to keep these lunatics in business.” His view is that if we did so “we might even see a few sensible ideas sprouting up”.

Angry and impotent as many people undoubtedly feel, is this the answer? Of course not. Using the author’s own rough-and-ready kind of argument, the dangers from a government which was free of any electoral mandate would be considerably greater than from governments which have (however unsatisfactorily) to answer for themselves. To throw away one’s vote is no step towards the freedom whose lack the book laments.

The real trouble, however, is that it never leaves the surface of things. There is no sign that Terry Arthur has ever asked “Why?” — why politicians do perennially dissemble, why ineptitude is the hallmark of every policy. The same kinds of observations were being made forty years ago by “Beachcomber”: “. . . the Prime Minister, that sheep in sheep’s clothing, rises to depths undreamed of in our history. The rumour that one of his sentences at Leeds was intelligible is a gross libel. Yet the maddest thing of all is that he can find people to go and listen to him . . .”

There is an explanation, and also a positive alternative. All the politicians and spokesmen he quotes have one thing in common — they support capitalism, and are endeavouring to run it (or suggest ways of doing so). The problems capitalism produces are organic, i.e. part of its nature. Whoever sets out to solve them has, therefore, a task which cannot be accomplished. Hence their politics present the spectacle of continual floundering from one quagmire to another, and the speeches are its rationale.

The alternative is to end capitalism and establish a sane society.

Robert Barltrop