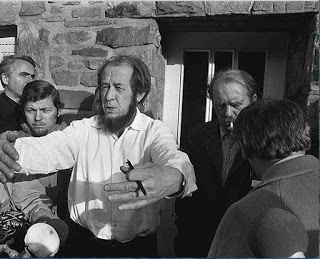

About Solzhenitsyn

So Solzhenitsyn is now able to voice his views openly. It is possible, for the first  time, to see how he measures up to the problems not merely of writers in Russia, but of all mankind. What can this Nobel Prize winner tell us?

time, to see how he measures up to the problems not merely of writers in Russia, but of all mankind. What can this Nobel Prize winner tell us?

Before weighing in with criticisms of his manifesto (Sunday Times, March 3), we must make it clear, first, that we have always opposed all forms of censorship, and secondly, that in criticising his ideas we are in no way defending the Kremlinite creed, to which we have consistently expressed our hostility. But however sympathetic we may be to one who has struggled successfully and has made his views heard in spite of all the Soviet censorship and suppression machine, we cannot applaud his political views.

We should like to have greeted him as a world citizen, an internationalist not a nationalist. But his views are based on an insular patriotism and Russian Orthodox Christianity. He believes in the myth of the “national interest”: indeed he bases his argument against a Russian war with China, not on the view that working-class interests are not at stake, but simply on the calculation that Russia could not win such a war and therefore it would be against Russia’s “national interest”.

Although apparently a fervent Leninist when he started his prison career, he is now a devout believer in Orthodox Christianity. If this is the result of incarceration in those inhuman prisons and labour-camps, it would seem to be an effective practical demonstration of the truth of Marx’s words:

Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the sentiment of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions.

On War and the Environment

In his manifesto Solzhenitsyn argues on two issues of the day. The first is the prospect of a Sino-Soviet war: he proposes that, since in his view ideology is the main cause of friction, the Russian government should abandon its ideology in the “national interest”. He seems to believe that, if this were done, there would be peace with China.

What the author of August 1914 should know is that nowhere can one find evidence of a war being fought solely because of ideology. Dogs may dislike each other’s colour or breed, but when they fight it is over a bone, or a bitch. Humans likewise don’t fight over creeds, but over markets and minerals, ports and provinces.

Solzhenitsyn’s second argument is not original and he names his sources — the Club of Rome and the Teilhard de Chardin Society. He has adopted their doomsday environmentalism, arguing against pollution and skyscraper cities and for a return to 2-storey houses and horse-transport. He sees a no-growth economy as the solution to the problems of mineral shortages, population pressures and pollution.

His argument, like that of other doomsday writers, takes no account of any possible re-structuring of society. Their computers are never programmed to tell us how world Socialism, with production for use not for profit, would employ the earth’s resources. Like the Club of Rome, Solzhenitsyn assumes that production for profit will go on for ever, and then argues that this system must be reformed to prevent it from destroying mankind’s habitat. Better surely to argue for an end to capitalism, since it is a system which generates waste and seeks constantly to increase the quantity of materials processed, year by year.

Solecisms Versus Marx

But when we come to his views on “ideology” it is plain that Solzhenitsyn has no knowledge of what Marxist theory really is. He has accepted the lies of the Kremlinites and so presents us with a distorted caricature of Marxism, a series of Aunt Sallys which he passionately shoots down in flames.

From this great sage, we learn that Marxism, “a primitive, superficial economic theory . . . declared that only the worker creates value and failed to take into account the contribution of either organizers, engineers, transport or market systems.” To start with, he ignores the fact that Marxist theory puts engineers and transport workers in the working class: they all have a living to earn, they all have to sell their labour-power. Also that in reckoning the value of a commodity, we take into account the wear and tear on machinery, the value of all raw materials used in manufacture and also any socially necessary labour time used in research and development (e.g. by engineers, organizers etc.)

The Marxist theory of value asserts simply that human labour is the sole source of value. But there is a lot more to Marxist economic theory than this basic proposition: to start with there are three volumes of Capital, and it is doubtful if even the sage Solzhenitsyn would describe them as “superficial”.

His other attacks on Marxism are similarly wide of the mark. Most of all he goes wrong on the question of revolution. According to him, Marxism “was mistaken through and through in its prediction that socialists could only come to power by an armed uprising.” Evidently Solzhenitsyn’s education in ideology did not include what Engels wrote on this subject:

The time of surprise attacks, of revolutions carried through by small conscious minorities at the head of unconscious masses, is past.

Indeed Engels argued that for a complete transformation of society to be undertaken successfully, it must be on the basis of full participation and the support of the mass of the community.

Again, according to Solzhenitsyn, Marxism is wrong in stating that the Socialist movement will come to the fore in advanced and highly developed countries first. We have only to use our eyes, to look at countries such as Russia which claimed to be “socialist” and see that this vaunted pseudo-socialism is merely a nasty form of capitalism. In 1917 the S.P.G.B. was pointing to Russia’s backwardness as an indication that the revolution could only bring about an acceleration of capitalist development. Now in 1974 Solzhenitsyn describes how Russian technology has copied Western technology, how pollution increases due to greed for profits and how the people are oppressed by poverty:

In practice, a man’s wage-level ought to be such that whether he has a family of two or even four children, the woman does not need to earn a separate pay-packet and does not need to support her family financially on top of all her other toils and troubles.

Russia is just as much a capitalist country as America or Britain, Cuba or Kenya. Everywhere the capitalist “mode of production” prevails: we see men and women who possess no land, no tools, nothing, who are driven by fear of want to sell their labour-power by the week or the month, mortgaging their lives in instalments so as to survive till the next pay-day. We see them producing goods galore, “an immense accumulation of commodities”, all their own work, yet they remain unable to afford most of what they need. We see human toil and human skills diverted from man’s real needs — food, clothing, health, housing, culture — to pander to the aristocracy of Big Business, the wasteful war-machine, the accountants, the luxury resorts, and so on.

This is what Marxists oppose: a worldwide system of exploitation of the many by, and for the benefit of, the few. A system which combines wanton waste with wasteful want. Shame it is that Solzhenitsyn has failed to join the movement to end it and has instead sided with those who say that authoritarianism can be made tolerable by reform. He is indeed one of those who “wear their chains with decency”.

Charmian Skelton