Architecture is not fulfilling its mission as long as it has not provided  a roof (tectum) for all that should be sheltered. In this sense it should concern itself with collective services, with the agglomerations.

a roof (tectum) for all that should be sheltered. In this sense it should concern itself with collective services, with the agglomerations.

No architect in this century has had more influence through his ideas, buildings, and books than

Le Corbusier. So much of modern architecture shows signs of his influence that it is impossible to imagine how different most of the buildings going up around us would have looked had he not existed. In city planning some of the methods he proposed 40 years ago — such as complete separation of cars and pedestrians — have only recently taken root in the minds of a few planning authorities. His ideas on almost every aspect of architectural design — from the free facade and buildings on stilts (

pilotis) to ‘brute concrete’ and sculptural building form, to name but a few — are still such a potent force and subject of controversy today that it may seem surprising that architects play down his political views (which he expressed no less strongly than his views on design) and even appear to ignore them.

But this is not really so surprising. To most architects and city planners politics is an embarrassment, and although every building programme is at the mercy of political and economic forces they consider these to be outside their professional scope altogether. Le Corbusier was notorious for his unique ‘arrogance’ and ‘outspokenness’. And although his political views were unsystematic, it is very encouraging to find this unique man starting out from the need to provide all his fellow-men with a decent environment and from there working out a programme similar in many respects to Socialism.

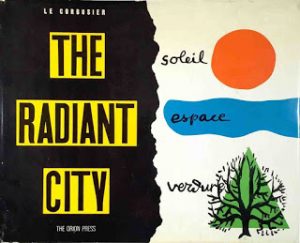

He was born in Switzerland in 1887. In 1933 his book The Radiant City (one of many) was published in France. (In a republished edition in 1964, the year before his death, he endorses everything he says in it.) The Radiant City is designed for leisure, sun, greenery, and open sky; large expanses of parkland separate rows of apartments; the playing-fields are right outside the apartments; the roofs are 60-foot-wide sun decks (beaches, in fact); the street no longer exists (except inside the buildings); homes are fully soundproofed and air-conditioned; there are nurseries, swimming-pools, and laundries minutes away, and industry in a separate zone two or three miles away (but minutes by car or bus) . . . Even though many architects disagree with various details of Le Corbusier’s scheme, it is hard to see how anyone can quarrel with the standards and quality he was aiming for. A utopia? Far from it—it was well within our technological and other resources back in 1930. Only the political structure prevented it then and prevents it now. Listen to what Le Corbusier says:

It is recognised that industry is submerging us with products that are irrelevant to our happiness. We have been propelled by machines into a false adventure, into a misadventure: these machines that can produce ten or 20 times as much as we ourselves ought to enable us to work at least five or ten times less. Modern industry, organised according to the laws of supply has inundated us with useless consumer goods. Wandering down this primrose path, allowing one thing to lead to another, we have finally allowed ourselves to be taken over entirely by what we call free competition, which is to say a form of slavery, which means that any effort is immediately countered by an opposing effort . . . we have become merely a flock of rams, horns locked together . . . The flock’s strength is drained away, yet it is not moving . . . we can make no progress! Free competition has been forced to invent advertising, the prospectus, the exhibition, product prizes, etc.: all those competing have to summon up all their energy to cancel out the efforts of their competitors.

It is indisputable that this frightful competition gives rise to the most violent emulation and effort.

But is it also certain that the human spirit is incapable of creative enthusiasm when faced with fruitful tasks?

An economy based on demand would put an end to the reign of the travelling salesman and the advertising agent, but it would necessitate a programme . . . for the production of useful consumer goods. Though not a narrow and exclusive one. The mind must always be left enough elbow room to satisfy its deepest purposes: quest for quality, supremacy, straggle and competition — but on the fertile soil of disinterest.

Our programme will concern itself with consumer products of a useful nature and with the redirection of industry onto the path towards its true aims; with providing work for all and guaranteeing every man his daily hours of freedom; and with providing physical sites and quarters designed to permit the man of today to enjoy this new freedom without constraint, instead of being hemmed in like a hare in an ever-dwindling square of wheat at harvest time.

(Le Corbusier’s own italics etc. throughout all extracts.)

Le Corbusier also underlines the socialist case in his attacks on money —though he doesn’t make it too clear whether he would get rid of it altogether or replace it with some ‘purer’ form of exchange.

Let us measure the full and cruel meaning of our present state: for some time now, we have been working merely for money.

A deceptive goal. It stimulates only a few of our qualities and leaves the most precious of them inactive. Worse, it encourages the defects in human nature . . .

If society were to reorganise itself, to distribute the fruits of its labour in a new way, then our concern for money could diminish, and our energies, freed in this way, would find the roads opened towards goals set by higher passions.

And of his programme for a new environment he says:

It means replacing the violent, savage, cruel and ruthless civilisation of money with another based on harmony and collaboration; one in which each member of society will feel himself a vital agent in this enterprise . . .

Le Corbusier realised that his plan for a Radiant City involved the ‘replanning’ of private property (though he did not go so far as to suggest abolishing it). In August 1932 he wrote that until then he had never found it necessary to discuss politics or economics; but through his professional life he had encountered an obstacle: unproductive property. Land which could form part of a wonderful human environment, in which the senses were no longer starved, in which freedom and privacy were possible, and in which work was cut to five hours a day and leisure used to the full, was lying waste — derelict, uncultivated, or misused.

Today we own land, but without any obligation to work it. In fact, a law which no-one would dream of disputing gives one the right to work it or not, just as one wishes.

And the ‘denaturalisation’ of property, he adds, made impossible the kind of work from which springs collective action. The present form of land tenure is invested with private rights antagonistic to the public right. ‘But if the public right is infringed, then THE INDIVIDUAL SUFFERS.’ And in the caption to an aerial view of Alsace, showing plots of farmland endlessly subdivided between heirs for generation after generation: “We live in a machine age, but machines cannot be used here.”

Capitalism forces its workers into the moulds that best suit its ends, regardless of whether these moulds cramp its workers’ spirit. Le Corbusier passionately resented this. He poured scorn on football stadiums and other ‘arenas’ in which the few are paid to perform while the many — whose need for active sport and whose ability to enjoy it is no less—sit and watch. He lamented the fact that most city-dwellers leave one compartment giving onto a street, (home) for another (work) and in between experience nothing but asphalt or stone under their feet, the ephemera of the daily paper or advertisements in their mini, poisoned air and smoke in their lungs, and barely a tree or a decent-sized stretch of sky, greenery, or water in sight.

But his programme had serious limitations.

Although he believed that architecture and city planning would, one day become extensions of politics, sociology, and ethics, he believed that ‘research into the correct solution for this problem (common ownership of land) is not part of the architect’s professional task.’ More food for the myth that ‘professional politicians’ are essential! But in fact Le Corbusier planned to toss the problem to another profession: the law. ‘Let the lawyers find a way!’ he exclaims. And:

It must be the task of our jurists to find a way of initiating the indispensable changes in present land tenure . . .

And although he wants international standardisation for building components, an international technical language, and so on, his thinking is still in national terms. He refers constantly to “mobilisation of the country’s land” (i.e. France’s) and to a national authority. Perhaps it is this acceptance of the nation state that leads him to accept war as inevitable — he points out the great advantages of pilotis for raising buildings above clouds of poison gas, and proposes armour-plated roof-decks to resist aerial bombardment.

Nevertheless, his political awareness is amazingly advanced compared with that of most architects. This is perhaps because his mental scope exceeded theirs. After all, it is terribly difficult to work out a viable political philosophy all on one’s own. There may be millions of people (architects among them) who, on having Socialism explained to them, will say: “That’s just what I’ve believed for a long time—but I could never put it properly into words!” And we believe with Le Corbusier that, despite the scornful laughter of cynics and spokesmen for capitalism, “there is a power for enthusiasm in the human soul that can be made to. explode”.

A.M.B.

a roof (tectum) for all that should be sheltered. In this sense it should concern itself with collective services, with the agglomerations.

Letter from Paul Otlet to Le Corbusier, 1928