Book Review: Capitalism in Kenya

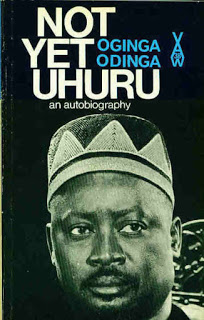

Not Yet Uhuru, by Oginga Odinga. Heinman Educational Books. 35s.

Not Yet Uhuru, by Oginga Odinga. Heinman Educational Books. 35s.

The people of Kenya have had the misfortune, reserved for colonial peoples, of experiencing two sorts of capitalism. One at second hand through colonial occupation, and the other, a more modern version, exploitation by capitalists of local origin and by the economic interests of the ‘advanced’ countries.

Today, control of the resources of Kenya is in the hands of large international firms and of the Kenya government. The local would-be capitalists and bureaucrats have certainly derived much benefit from independence, but the vast majority of the people of Kenya, who were at one time led to expect a post-independence egalitarian Utopia, have been disappointed.

In this autobiography we learn well how the “benefits” of capitalism were first introduced to Kenya. There is an interesting survey of early land-appropriation by the British authorities and of the break-up of the tribal system through forced wage- labour. Odinga is particularly good in his account of the Mau Mau uprising and the reasons for it. Once the rebellion presented a real threat to British authority in Kenya, and thus to British economic interests, ruthless measures were taken. All civil liberties were suppressed—an African could be arrested in the street at any time. All Kikuyu (the main tribe concerned in the rebellion) were forced either to collaborate with the authorities or to join the Mau Mau bands as a result of persecution. British capitalism wanted to hold on to Kenya so as to have an assured and cheap supply of raw materials and a market monopoly.

Today, some four-and-a-half years after independence, things have not changed much. The people of Kenya are now exploited not only by businessmen with white skins, but also by civil servants and politicians who have somehow succeeded in securing company directorships and land. Little free expression of opposition to the government is allowed. The only consolation that the people may draw is perhaps in seeing men with skin the same colour as theirs replacing white colonists at the wheels of large motor-cars manufactured in West Germany.

Odinga is allowed, probably by virtue of his popularity (he was at one time Vice-President of the republic and Kenyatta’s right-hand man) to lead a tiny opposition of nine in parliament. His party is, however, allowed few extra-parliamentary ‘privileges’ such as the holding of public meetings or recruiting campaigns.

This autobiography, as well as being a good document of British colonial history, is worthwhile reading because part at least of Odinga’s conclusion is acceptable. Odinga himself left high state office for the political wilderness because he saw that national independence does not in itself end servitude for the mass of the people. He also recognises the oligarchic character of the present Kenyan government. To solve these problems, however, he presents a creed which he calls “African Socialism”. The use of the word “Socialism” in independent Africa is very common but worth little. It is used, for instance, by both government and opposition in Kenya. The general purpose of this is clear: to give obviously oligarchic governments a facade of popular support and concern for justice and equality.

Odinga’s “African Socialism” would take the form of “a Kenya government backed by popular enthusiasm and national mobilisation”. We suggest to the people of Kenya, and indeed to the people of the world, that the only way they will solve their problems will be by overthrowing capitalism which deprives and degrades them. This can only be done, not on a national scale, but by an internationally united working class who reject all leaders and governments.

Not Yet Uhuru (freedom) is the personal and political testament of a sincere, but unfortunately misguided, political figure. It is well worth reading for the insights which it offers into the lot of the people of Kenya.

Amit Pandya