Book Review: ‘The First World War – An Illustrated History’

The First World War

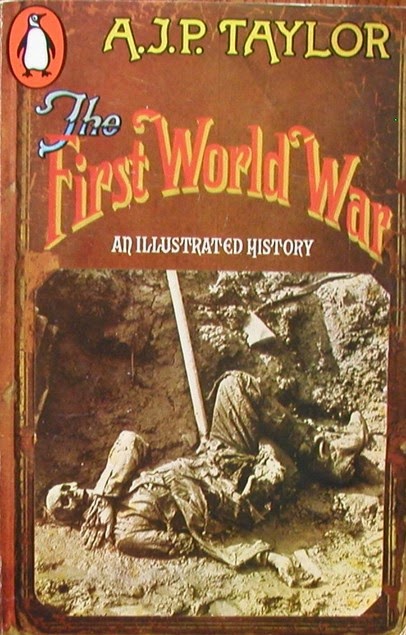

The First World War: An Illustrated History by A. J. P. Taylor (Hamish Hamilton)

Perhaps Mr. Taylor is, in the strict sense of the word, our most eminent modern historian. Yet whatever a man’s knowledge, nobody should be deluded into believing that his conclusions are unassailable.

Perhaps Mr. Taylor is, in the strict sense of the word, our most eminent modern historian. Yet whatever a man’s knowledge, nobody should be deluded into believing that his conclusions are unassailable.

Consider, for example, Mr. Taylor’s opinion on the cause of the First World War:

“Men are reluctant to believe that great events have small causes. Therefore, once the Great War started, they were convinced that it must be the outcome of profound forces. It is hard to discover these when we examine the details. Nowhere was there conscious determination to provoke a war. Statesmen miscalculated. They used the instruments of bluff and threat which had proved effective on previous occasions. This time things went wrong. The deterrent on which they relied failed to deter; the statesmen became the prisoners of their own weapons. The great armies, accumulated to provide security and preserve the peace, carried the nations to war by their own weight.”

and

“The First World War had begun—imposed on the statesmen of Europe by railway timetables. It was an unexpected climax to the railway age.”

Now this may appeal to those who hold the “accidental” theory of history. But that theory does little more than spell out the process of events; it tells us nothing about the causes of those events nor does it illuminate the larger canvas of human history in all its social phases. Like the 1914/18 soldiers’ song, it says, in effect, that we are here because we are here because . . .

The theory that the First World War was an avoidable accident ignores the previous history of Europe. It ignores the outcome of the Franco-Prussian War, the German ambitions in Africa and the Middle East and the threat which an expanding German capitalism represented to the established European powers. It ignores, even, the very fact that nobody tries to ignore—the massive build up of military strength on the Continent before 1914 and it certainly tells us nothing about the reasons for that build up.

Mr. Taylor, in truth, cannot ignore this fact: –

“The German general staff did not believe that they could conquer decisively if they had to fight at full strength on two fronts, against both France and Russia at once. Therefore they had long planned, ever since 1892, to put practically all their armed weight in the west and to knock out France before the slow machine of Russian mobilization could lumber into action.”

And if there is a contradiction in a theory which says that a war can break out by accident, although one power has planned for over twenty years to knock out another—well, that is Mr. Taylor’s contradiction, not ours. We know how fallible the experts can be.

Apart from this, Mr. Taylor is fashionably harsh upon the generals (one picture of Sir John French, in morning coat and topper hurrying through a crowd, describes the B.E.F. commander as ” . . . in training for the retreat from Mons.”) and favourable to Lloyd George. The photographs are nothing less than brilliant; each one loaded with the atmosphere of its time. Here are pain and courage, pathos and provocation. Look at these pictures again and again—there seems to be something fresh there every time.

Those from the fighting itself are positively horrific—a legless French soldier, some Tommies who have been blinded in a gas attack and stand dumbly in line, each man guiding himself by his hand on the shoulder in front. The pictures from the home front are no less impressive. The shot of the Eton schoolboys on their way to dig over some plot shows how timeless are the fashions and the demeanour of our master class. These boys could have been photographed yesterday—unlike the working class lads who, on page 21, are cheering the volunteers outside a recruiting station.

And the pictures are supported with biting captions.

The First World War released a flood of human suffering such as few had foretold in 1914. It slashed a great gap into a hopeful generation and it wrecked Europe’s morale. Yet in 1939 they were ready to go into it again, ready with the uniforms and the flags and the claptrap about the glory of war.

Let those workers who urge their fellows into uniform study the photographs in this book. Let them smell the mud and the cordite, feel the tight fear of men about to go over the top, share the endurance of a civilian population under bombardment. And let them see, almost at first hand, the pompous cynicism of the generals and the statesmen—the leaders who are at their most beloved and trusted when the world is at its deepest in agonised confusion.

Ivan