Film Review: The Prisoners Story

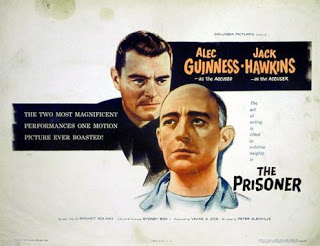

The Prisoner is based on Bridget Boland’s play of the same name which had a short run in London a few months ago. The play, which was one of the very few worthwhile serious plays shown in London in the past year or so, had two of the  main characters in common with the film—Alec Guinness as the Cardinal and Wilfred Lawson as the warder. The interrogator, the other principal character, is played in the film by Jack Hawkins.

main characters in common with the film—Alec Guinness as the Cardinal and Wilfred Lawson as the warder. The interrogator, the other principal character, is played in the film by Jack Hawkins.

It is a story of a Cardinal in an iron curtain country who has fallen foul of the regime by his outspokenness. The authorities, however, are unable to merely arrest and liquidate him owing to his fame and popularity, and it is therefore necessary for them to extort from the prisoner a confession of crimes sufficient to discredit him and to ensure his fall from public favour. In the words of the interrogator: “You are a public monument and that monument must be—defaced.”

The story, then, deals with the efforts of the interrogator to discover the chink in the Cardinal’s armour that will enable him to break down his resistance and eventually bring about his public recantation and “confession.” The interrogation takes months and although the prisoner is subjected to no actual physical torture, his spirit is broken by solitary confinement, the complete absence of sunlight and other well-thought-out “psychological” methods of torture. Inevitably roe chink in the armour is discovered and exploited and the State triumphs, although the interrogator discovers in the process that he himself is not free from pity, and is bringing about his own destruction as much as the prisoner’s. The interrogator’s method of breaking the prisoners’ will (or “curing him” as the interrogator puts it) and the Cardinal’s struggles to thwart him make a fascinating, although horrifying, study.

Any other conclusion to the story would have been dishonest for, in fact, in the so-called “Communist peoples’ democracies” the State has always triumphed.

Bridget Boland has also written the script for the film and, unfortunately, has been prevailed upon to embellish the severity of the play with some romantic interest and some other tiresome, Hollywoodesque, film conventions, presumably at the instance of the box-office experts. The action of the play took place completely in the interrogation room and in the prisoner’s cell, but there are a number of outside episodes added to the film that are both distracting and pointless. For instance, there is the disjointed love story of one of the police-warders; then a young boy is shot by the police while chalking “ Freedom” signs on a wall; a gun-battle breaks out between troops and an armed man in a house; a subversive journalist is arrested in a cafe; and so on. The addition of these episodes ruins the original unity of the play, and makes the film crudely anti-Communist, sprawling and inconsequential. Less reprehensible, perhaps, is the addition of the Cardinal’s arrest in the cathedral and the trial. Both are quite effective but again, add little to the unity and point of the original.

The political trials that have taken place in Russia and the other so-called “Communist” countries generally follow a consistent pattern. At the trial the accused generally gives an abject “confession”; admits to all his crimes; extolls the virtues of the leaders of the party; admits the complete wrongness of his thought and sometimes even demands that the maximum penalty be exacted for the benefit of the people he is confessing that he has betrayed! A few extracts from the accounts of some of these trials should be sufficient to demonstrate this.

Trial of Zinoviev, Kamenev, and others. (Russia, 1936):—

“Vishinsky: How is one to judge the articles and declarations which you wrote in 1933 and in which you expressed devotion to the Party? As deceit?

Kamenev: No, worse than deceit.

Vishinsky: Breach of faith?

Kamenev: Worse.

Vishinsky: Worse than deceit, worse than breach of faith. Do you find this word? Is it treachery?

Kamenev: You have said it.

Vishinsky: Zinoviev, do you confirm this?

Zinoviev: Yes.”

Trial of Traicho Kostov and others. (Bulgaria, 1949):—

Kostov: “So I repeat, I plead guilty of nationalist deviation in relation to the Soviet Union, which deserves a most severe punishment”—and—“I must confess that my readiness to put myself at the disposal of the British Intelligence Service was due partly to my left-sectarian, Trotskyist convictions of the past as well as to my capitulation before the police in 1942 . . . ”

Nikola Nachev at the same trial:—

“Citizen Judges, having fully realised my criminal and hostile activities, carried on by me against my Fatherland and the Bulgarian people, I have described these activities in my written depositions before the People’s Militia. I will now tell you about what I did and what I know, so that the criminal conspiracy in which I also participated may be revealed. . . .”

One could go on quoting indefinitely this kind of thing. No one in their right mind could accept these confessions as being genuine and it is impossible not to feel uneasy when thinking of the methods which must be resorted to in order to obtain them. George Orwell in “Nineteen Eighty-Four” has, perhaps, described these methods in their ultimate form. For example, when O’Brien is explaining to Winston Smith the methods and ideals of the party he says, “Shall I tell you why we have brought you here? To cure you! To make you sane! Will you understand, Winston, that no one whom we bring to this place ever leaves our hands uncured? We are not interested in those stupid crimes that you have committed. The Party is not interested in the overt act; the thought is all we care about. We do not merely destroy our enemies, we change them.”

It is ironical to think that after thousands of years of human progress, a large part of the world’s population exists without even those elementary freedoms that the workers in this country possess, but this in itself does not justify despair, for though tragic failures, the Berlin riots and the Vorkuta rising are two signs that the “Communist” dictatorships do show cracks.

However, to return to the film. It merits a visit in spite of its faults, not only because of the superb acting performances of the three principals, but also because it throws some light on one of the most remarkable social phenomena of our time:—the political trial.

Albert Ivimey