“Plebs” and Pounds

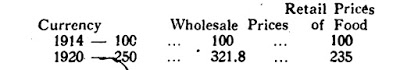

When the temporary boom that followed the Armistice began to decline, the capitalist class instructed its agents in Press and on platform to give forth “reasons” for prices remaining high in this country, despite the wage reductions that were being enforced in all directions. One of the favourite “reasons” put forward to explain this apparent puzzle was “the inflation of the currency.” Tory and Liberal politicians, as well as economists from Cassel to J. A. Hobson, repeated this parrot cry without offering the slightest evidence in support of it.

The Labour Party conducted a so-called investigation into the matter of high prices and borrowed, without examination, the assertion of “inflation,” and gave it as one of the chief causes of those high prices.

An article appeared in the July, 1920, Socialist Standard, which, among other things, made a brief reference to this point of ‘‘inflation.” This called forth some correspondence that was dealt with in the September and November, 1920, and April, 1921, issues. The question was raised once again by a correspondent in the June, 1922, Socialist Standard, and answered in the same issue.

This answer has evidently upset some of the self-styled experts, as two issues of the “Plebs” Magazine (July and September, 1922) have been forwarded to us, that contain the complaints of certain correspondents about the “Plebs” repeating, parrot-like, the stupid assertion on “inflation.”

We have never accused the statesmen of the Labour Party of being guilty of any economic knowledge—Marxian or other— but the “Plebs” claims to be a journal for the spread of Marxian education, and it is the “organ of the National Council of Labour Colleges.” If their treatment of this question of “inflation” is a sample of their knowledge, it certainly shows the value of Labour College “education.”

In attempting to discuss any question, the first thing to be done is to settle the facts of that question and then use those facts to build up one’s case. In the question under discussion obviously the first point to be settled was “Has there been an inflation of the currency in the United Kingdom? ” The inquirer will be astonished to find that neither the Labour Party nor the “Plebs” have made the slightest attempt to examine—let alone settle—this fundamental point. Such is the slovenliness of the “Plebs” in dealing with statements devised to deceive the working class. In these circumstances a brief re-statement of the case will be useful.

The currency of a country consists of the article, or articles, that are chosen by general consent and experience to act as measure of value and medium of exchange. At first this is usually an ordinary commodity that is in general use. When the number and complexity of the exchanges grow to .a certain point the need for some guarantee of the invariable quality and weight of the medium of exchange is felt. This duty, sooner or later, devolves upon the Government of each country, and is usually done by stamping the articles concerned with some special device. The stamped article now takes up a new position in the commercial world and is removed from the place of an ordinary commodity to function exclusively as the measure of value, medium of exchange, etc. It thus becomes the currency of that country. Once the main use of a currency is understood the “problems” connected with it will be easily understood.

As the currency is used as a medium of exchange, it is evident that the amount of currency required at any given time will be determined, first by the total of the prices of the commodities exchanged at that time. This quantity of currency will be modified in practice by the amount of credit given by the sellers, which defers payment to some future date; by the number of payments falling due for articles previously sold; and by the speed at which the currency circulates. Thus, if £1 makes 52 moves in a given period—a year—it will circulate £52 worth of commodities in that time. Cheques, bills of exchange, etc., all add to the factors modifying the quantity of currency required, but these do not alter the main argument. Each country finds by experience the quantity of its own currency required to cover the total of the exchanges and transactions during a given period. This quantity will vary from time to time, particularly in the relative sense, but under normal circumstances these variations are easily met.

(3) The holder of a currency note shall be entitled to obtain to demand, during office hours at the Bank of England, payment for the note at its face value in gold coin which is for the time being legal tender in the United Kingdom.

If our comrade would like a summer holiday as the guest of His Majesty she has only to change her £1 currency notes into gold sovereigns, smelt them or sell them by weight for export. If she did succeed in doing this secretly she would find that a gold £1 outside of England bought more than a paper £1. Even inside England she would find people who would give her more than 20s. for it.—(Plebs., July.)

If enough currency notes were issued then they would exchange precisely on the basis of the socially necessary labour needed to reproduce them. —(Plebs., September, 1922.)

The Standard writer, instead of simply answering a question, recites his little piece about how the S.S. has always denied inflation; and it is his remarks apparently which have worried the Bentley class.—(Ibid.)

But increase in credit and increase in currency react upon each other and it is certainly wrong to deny that inflation of currency was not a factor behind high prices in our own country. The fact that the “Fisher” is convertible does not prevent inflation for it is only convertible in theory.—(Ibid.)