Theatre Review: ‘The Silver Box’

On March 20th, “The Silver Box,” by John Galsworthy, was produced at the Court Theatre. The play was written some years ago, and in spite of some care in bringing details up to date, the atmosphere remains rather old-fashioned. But in essence it is as true as formerly, being concerned with the subjection of the propertyless to those who own the means of life. The economic relation is shown reflected in the privilege which in every department of social life is secured to the ruling class, and the savage dissatisfaction of the more spirited among those who suffer by it.

On March 20th, “The Silver Box,” by John Galsworthy, was produced at the Court Theatre. The play was written some years ago, and in spite of some care in bringing details up to date, the atmosphere remains rather old-fashioned. But in essence it is as true as formerly, being concerned with the subjection of the propertyless to those who own the means of life. The economic relation is shown reflected in the privilege which in every department of social life is secured to the ruling class, and the savage dissatisfaction of the more spirited among those who suffer by it.

An unemployed man, exasperated by long privations and indignities, steals a silver cigarette-case on an impulse of drunken spite. The son of a wealthy Member of Parliament is also guilty of a drunken freak —makes off with a harlot’s purse. The offences are parallel: but by reason of his fortunate social position the one escapes the consequences of his action, the other is convicted and the tragedy involves his family.

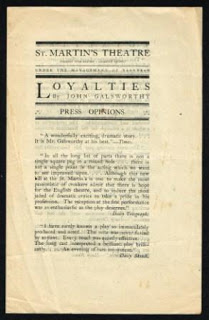

Galsworthy has a clear eye for social antagonisms, of which the most irreconcilable is the conflict of interests appearing as the class struggle. He sees that it is not possible to act upon one set of principles without coming into collision with men who hold to another. “Our loyalties cut across one another,” “To be loyal is not enough,” are the themes of his latest play at St. Martin’s Theatre.

Though the author was not here treating of the class-war, the first observation can with truth be extended to it. The more steadfastly masters’ and workmen prosecute their respective interests, the completer the solidarity of each class, the more intense is the hostility between them. Only when classes are merged in the Socialist Commonwealth will such contention disappear. But let no enthusiast deem, therefore, that employers and employed alike are to be enlisted in the cause of its establishment: that the class which fights with advantage, and to which fall the spoils of the contest, will throw down its superior weapons and restore the plunder, with no other inducement than a perception of the excellence of harmony among men. No. The revolution will be achieved, not only without its assistance, but in despite of its utmost opposition.

From time to time good people, grieved by present misery and impatient for its cure, make a bid for the co-operation of capitalists by endeavouring to formulate a scheme which shall recommend itself to both masters and workers as “a more equitable organisation of social life.” Setting aside the impracticability of arbitrarily modifying the capitalist system, and the question of how far anything other than Socialism would prove a remedy for the evils they deplore, what is less possible than at once to satisfy two antagonistic ideas of equity?— the one requiring the recognition of private property in the means of production, and consequently to the wealth produced; the other holding that since labour applied to the earth is the sole source of wealth, those who produce have a common title to the fruits of their labour.

A careful reading of history will show that human societies advance by stages, each one of which is marked by equitable organisation—according to the ideas of the then ruling class, and tyranny—according to the revolutionary class. Once it was the rising capitalists of England who shattered feudalism in what Walton Newbold aptly calls “the great struggle for Right, the Right of Property in Hand and Credit.” Next will come the turn of the workers, who will set free for the service of mankind the great powers which capitalism, though it has developed them, cannot profitably em- ploy.

To the working class, then, belongs the mission of putting an end to economic conflict, and so to the hatred and wretchedness which grow from it. With its emancipation the world takes another leap forward. For the worker to be loyal to the aspirations of his class is enough: for devotion to the Socialist ideals is in our day the truest service to the human race.

N. P. M.