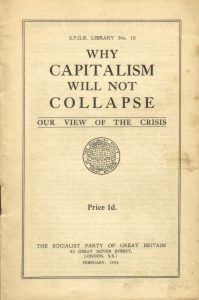

FOREWORD

FOREWORD

We are in the midst of a crisis that is world-wide. Every country feels its ravages. Millions and millions of workers are unemployed and in acute poverty. Everywhere there is discontent and a feeling of insecurity, and the prestige of even the strongest of governments has been shaken. All sorts of emergency measures have been hastily adopted, but the depression still continues. Working men and women who normally ignore such questions, are now asking why the crisis has occurred, what will be its outcome, and whether it could have been avoided. In some minds there is a fear, and in others a hope, that the industrial crisis may bring the present system of society down in ruins, and make way for another.

The Socialist Party of Great Britain answers those questions in this small pamphlet. The answer is worth the consideration of every working man or woman, as it concerns the great social problem—the problem of poverty. Our views on the crisis are set out here with the hope that workers who read them may be led on to study more seriously the principles of Socialism. One great obstacle has first to be overcome. The worker, seeing the inability of the experts to agree among themselves, may doubt his own capacity to understand the problem that other and seemingly wiser heads have found so baffling. Do not be put off by that idea. Working men and women, who make and tend the wonderful machinery of modern industry, and who carry out the intricate operations of trade and finance, have powers of thought that are well able to grasp the basic problems of politics and economics. We who address you are also workers, and we know that only the lack of desire and of confidence has hitherto prevented the mass of the workers from thinking these things out for themselves.

The reader is asked to remember that this pamphlet is not merely the opinion of an individual—it is the view of the Socialist Party. Moreover, it is not the product simply of the present trade depression. It is based upon the writings of many who have given special study to past crises and to the workings of the social system in which these crises have taken place. We are especially indebted to the fruitful and painstaking work of Marx. The S. P. G. B. has held the views set down here, not for a short while only, but ever since its members took up the problem at the formation of the Party over 27 years ago. All that has happened since has confirmed our view of crises. It has also deepened our conviction that in the theory of Marx the wage-earners will fund valuable instruments with which to work for their emancipation.

I. FEARS THAT CAPITALISM WILL COLLAPSE.

The purpose of the Socialist Party is to show the working class the need for a complete alteration in the organisation of society. The basis of Capitalism is the private ownership of the land, the factories, the railways and the rest of the means of life. This is the root cause of poverty, insecurity and wars, and of a whole host of other evils. The remedy lies in making the means of production the common property of society. In other words, the working class must replace the existing social system, known as Capitalism, by a system of common ownership and democratic control, known as Socialism. But our work has been made more difficult by the idea that Capitalism may collapse of its own accord. It is clear that if Capitalism were going to collapse under the weight of its own problems then it would be a waste of time and energy to carry on socialist propaganda and to build up a real socialist party aiming at political power. If it were true, as is claimed, that Capitalism will have broken down long before it will be possible for us to win over a majority for the capture of political power, then, indeed, it would be necessary to seek Socialism by some other means. Workers who have accepted this wrong and lazy idea of collapse have neglected many activities that are absolutely essential. They have taken up the fatalistic attitude of waiting for the system to end itself. But the system is not so obliging!

At first sight there seems to be a ground for this idea. Capitalism from time to time develops acute industrial and financial crises; and at the depth of these it does appear to many observers that there is no way out, and that society cannot continue at all unless some way out is found. Men of very different social position and political convictions have been driven to this conclusion—reactionaries and revolutionaries, bankers and merchants, employers and wage-earners.

Let us go over some of the statements made by those who have foretold collapse, and notice how much alike they are. Notice, too, how each one falsifies the preceding ones. The fact of another crisis taking place is proof enough that the earlier crises did not turn out to be insoluble—the patient cannot have more than one fatal attack.

During the 19th century there were about ten well-marked crises. One commenced in England in 1825. William Huskisson, a former President of the Board of Trade, wrote about it in a letter dated 30th December, 1829:

“I consider the country to be in a most unsatisfactory state, that some great convulsion must soon take place . . . I hear of the distress of the agricultural, the manufactural, the commercial, the West Indian, and all trading interests. . . I am told land can neither pay rent nor taxes nor rates, that no merchant has any legitimate business . . . I am also told that the whole race of London shopkeepers are nearly ruined” (Huskisson Papers, pub. Constable, 1931, page 310).

Another crisis occurred in the eighteen-eighties, and was dealt with by Lord Randolph Churchill in a speech at Blackpool, in 1884:

“We are suffering from a depression of trade extending as far back as 1874, ten years of trade depression, and the most hopeful either among our capitalists or our artisans can discover no signs of a revival. Your iron industry is dead, dead as mutton; your coal industries, which depend greatly on the iron industries, are languishing. Your silk industry is dead, assassinated by the foreigner. Your woollen industry is in articulo mortis, grasping, struggling. Your cotton industry is seriously sick. The ship-building industry, which held out longest of all, is come to a standstill. Turn your eyes where you will, survey any branch of British industry you like, you will find signs of mortal disease” (Lord Randolph Churchill by Winston Churchill, M. P., pub. Macmillan & Co Ltd, London, 1906, Vol 1, page 291).

There is one important thing to notice about the two statements above. Huskisson wrote at a time when England was a protectionist country. He was an advocate of free-trade. Lord Randolph Churchill spoke at a time when England had long been a free-trade country. He was an advocate of protection. It is clear that neither free-trade nor protection offers a solution for trade depressions, and that the return to protection in March, 1932, will not prevent further crises.

Of late we have been asked to take a very serious view of the alleged “adverse balance of trade”, by which is meant that this country has had more imports than exports, with the consequence that debts have been incurred abroad to the extent of the excess imports. The facts are still the subject of argument, but it is not necessary to go into that question. All that we need to remember is that the fears about the “adverse balance of trade” are not new.

In a paper read to the Royal Statistical Society on December 19th, 1876 (see Trade, Population and Food, by S. Bourne, pub G.Bell and Sons), Mr. Sidney Bourne who for many years was in the Government Service, engaged in the compilation of trade statistics, painted an alarming picture of Great Britain’s trade. He argued that serious consequences would follow if the adverse balance (which he pointed out was then in evidence) was allowed to continue. He mentioned, too, the considerable and influential body of political and public men who shared his views.

After making the adjustments he considered necessary on account of income from investments owned abroad by British subjects, and the so-called “invisible exports” (i.e. the services, such as shipping and financial services, that are paid for by foreigners, but which do not take the form of actual articles passing through British ports), he declared that there was an “adverse balance” in the years after 1872.

He said:

“In 1872 the true excess would seem to have been on the side of exports rather than imports, to the extent of nearly £4,000,000; but in the following year the imports again predominated, and have continued to do so with increasing weight up to the present moment” (page 69).

Mr. Bourne, like many modern observers of the course of trade, was apprehensive about the future:

“I firmly believe that Britain now stands tottering on the eminence to which she has attained, and.

In passing, we may notice that one of Mr Bourne’s suggested remedies for avoiding the threatened doom of Great Britain has a familiar ring today. It was that the “lower classes” should drink a much smaller quantity of intoxicants. Another was that the rich should “restrain the heavy expenditure accompanying cravings of ambition, the undue pursuit of pleasure and frivolous idleness” (page 74).

It is not necessary to deal with the pessimistic utterances of public men at every crisis; it is sufficient to say that each period of trade depression produces its prophets of catastrophe. We may add, however, that those politicians and business men who foretell collapse now are no more to be relied upon than the others who foretold collapse in past crises. They do not understand the workings of the system that they defend. As recently as 1931 we saw this strikingly illustrated in the abandonment of the gold standard by Great Britain. During August and September we were told that chaos would ensue if that abandonment took place. When it happened everything went on much as before, to the astonishment of the economic “experts” who are supposed to understand these things.

We can leave them and concern ourselves rather with the acceptance of the idea of collapse by those claiming to be socialists. The policies and actions of the workers have been, and will continue to be, powerfully influenced by their theories about the way in which Capitalism works and about its future developments. Wrong theories lead to wrong and dangerous actions.

II. THE IDEA OF A BLIND REVOLT OF THE WORKERS

The defenders of Capitalism who have been panic-stricken in times of crisis, have sought for ways to save the social system, which they believed to be in danger. On the other hand, many who desired Socialism have looked at industrial crises not with fear but with hope. They have thought that in a time of great unemployment and distress the majority of workers, although not socialists, would be forced by their sufferings to revolt against the capitalists and their government, and that they would place in power a government which would try to remould society on a socialist basis.

One of the organisations to hold this view was the Social Democratic Federation. The late H. M. Hyndman, who was prominently associated with the S. D. F., thought that Socialism might be expected as the result of almost every one of the crises that occurred in the period from 1881 onwards. Thus, in 1884, in the paper Justice (January, 1884), he made the following declaration:

“It is quite possible that during this very crisis, which promises to be long and serious, an attempt will be made to substitute collective for capitalist control. Ideas move fast; the workers are coming together”.

Later on he suggested 1889 as the probable date for the revolution (see Rise and Decline of Socialism by Joseph Clayton, pub 1926 by Faber & Gwyer, p.14). Edward Carpenter in My Days and Dreams, says:

“It was no wonder that Hyndman . . . becoming conscious as early as 1881 of the new forces all around in the social world, was filled with a kind of fervour of revolutionary anticipation. We used to chaff him because at every crisis in the industrial situation he was confident that the Millennium was at hand” (pub, Allen Unwin Ltd, 1916, page 246).

Hyndman continued to see the revolution “round every corner”, until the date of his death, in 1921.

Similar ideas are held by members of the Labour Party and Independent Labour Party, and they were handed down from the Social Democratic Federation to the parties that in 1920 became the Communist Party of Great Britain. It is indeed probable that the Russian Bolshevist leaders, many of whom hold these views, learned them during their exile in England round about the beginning of the century.

The communists provide the clearest example of a party holding this theory and trying to act upon it. In The Communist (22nd October, 1921) it was frankly stated that those who founded the Communist Party of Great Britain were “impelled by the conviction that the capitalist economic system had broken down”, while Mr W. Paul, a prominent communist wrote in the communist journal, The Labour Monthly (15th February, 1922):

“The most important fact in modern history is the breakdown of capitalism . . . there is the greatest possibility that the social revolution may take place in the immediate future”.

In July, 1926, The Labour Monthly stated that:

“The decline of capitalism in Britain, whether measured in the figures of trade or of production, has developed at a startling and accelerated pace between 1921 and 1926”.

In 1928, in a Communist Party book, The Decline of Capitalism, the author, E. Varga, declared (p. 7):

“It is no longer a ‘dying’ capitalism, but one already in the process of mortification . . .”

In the October, 1931 Labour Monthly (just before the General Election), Mr. Dutt, the editor, wrote in a manner indicating the utmost excitement at the likelihood of a decisive crash: “The fight is here”, “the crisis marches on relentlessly”, “it is the whole basis of British Imperialism that is now beginning to crack”, “the whole system is faced with collapse”, “the hour of desperate crisis begins”; and much more to the same effect.

Mr. James Maxton, M. P., putting the I. L. P. point of view, has been as confident as the communists. He made a speech at Cowcaddens on 21st August, 1931, reported as follows in the columns of the Daily Record, 22nd August, 1931 (Reprinted in Forward, 12th September):

“I am perfectly satisfied that the great capitalist system that has endured for 150 years in its modern form, is now at the stage of final collapse, and not all the devices of the statesmen, not all the three-party conferences, not all the collaboration between leaders, can prevent the system from coming down with one unholy crash”.

The Daily Record report goes on to describe Mr. Maxton’s speech:

“‘They may postpone the collapse for a month, two months, three months, six months’, he cried, forefinger pointing at his audience, and body crouched, ‘but collapse is sure and certain’”.

In contradiction to those who hold this theory of an automatic collapse of Capitalism, the Socialist Party of Great Britain has never deviated from opposition to that view. Our knowledge of past history and of the way in which the social system develops, convinces us that no crisis of Capitalism, however desperate it may be, can ever by itself give us Socialism. Socialism cannot come by stealth. It can only come by the deliberate act of workers who understand Socialism, and are organised politically to obtain it through control of the machinery of government. The blind revolt of desperate workers would cause great distress and destruction. It might prove troublesome to the capitalist authorities, who would have to exert themselves to suppress it, but the outcome would not be Socialism.

Why are we so confident of this? In the next section our confidence is explained.

III. THE CAUSE OF CRISES

The cause of trade depression is really a simple one to understand. Highly developed Capitalism, while condemning the vast number of workers to a meagre standard of living, causes extraordinarily large incomes to flow into the pockets of a small section of the population (i. e., those who own the factories, the land, the railways, etc.). Most wealthy people have incomes so large that they do not spend anything like the whole amount. After having purchased all they need, often including luxuries of the most extravagant kind, they still have a large surplus that they seek to invest in profitable concerns. But these concerns are in competition, each trying to sell goods more cheaply than the other. In order to maintain and, if possible, increase his profits, each employer tries to get from his workers a larger output at a smaller cost. By means of labour-saving machinery and methods the same quantity of goods is produced by fewer and fewer workers, and displaced workers are constantly added to the army of unemployed. The unemployed man or woman, having only unemployment pay to spend, cannot buy as much as formerly. Thus buying is curtailed while all the time efforts are being made to increase production—a contradiction that is bound to result in over-stocked markets and trade depression. During a depression, this situation is worsened by wage reductions.

The depression shows itself, every few years, in the accumulation of stocks of goods in the hands of retail stores, wholesalers and manufacturers, farmers and others. While trade is relatively good each concern tries to produce as much as possible in order to make a large profit. It is nobody’s business under Capitalism to find out how much of each article is required, so that industries quickly expand to the point at which their total output is far larger than can be sold at a profit. Quite young industries like artificial silk, soon reach the degree of over-development shown by the older industries. Goods such as farm crops, that are ordinarily not produced to order, but with the expectation of finding a buyer eventually, naturally tend to accumulate to a greater extent than those produced only to order—such as railway engines.

As traders find it more difficult to sell, they reduce their orders to the wholesalers, who in turn stop buying from the manufacturers. Plans for extending production by constructing new buildings, plant, ships, etc., are cancelled and the workers are laid off.

The reduced income of the workers and of the unemployed reduces still further the demand for goods. In desperate need of ready money to pay their bills, retailers, wholesalers and manufacturers are driven to sell their stocks at lower and lower prices—often at a price less than the original cost price. Workers, for the same reason, are forced to offer to work for lower wages. It is not that there is any lack of money, but that the rich who have it can find no profitable field for investment. The economies that are made in a time of depression—whether voluntary ones, or economies enforced on the workers by wage reductions, actually aggravate the crisis instead of relieving it. Yet “economise” is the advice given by public men now, as it was by Mr. Bourne in 1876, referred to earlier in this pamphlet.

Here is a situation that always causes grave discontent. It is from this discontent that the believers in the theory of the collapse of Capitalism think that they can draw the force which will overthrow the capitalist system. But it does not work out like that. In spite of riots and agitations, Capitalism still continues. The actual events show us why this is and why it must be so.

IV. WHAT HAPPENS IN PRACTICE

Since the War, to go back no further, the situation has been tested many times and in many places. The result has always been the same—suffering for the workers without compensating gain.

In Great Britain two outstanding events may be considered. First, there was the great depression of 1921 and 1922, when, as now, unemployment was between 2,000,000 and 2,500,000. Then, in 1926, there was the spontaneous demonstration of sympathy with the miners in their resistance to wage reductions, that resulted in what is known as the “General Strike”. Since the communists have been the most persistent advocates of the doctrine we are attacking, let us see what came of their efforts to take advantage of these two crises.

Round about 1921 and 1922 the communists claimed that they had the leadership of the hundreds of thousands of members of the unemployed organisations. They organised marches and demonstrations, deputations to Cabinet Ministers and local authorities, and attempted to seize public buildings. They did everything they could to force the authorities to grant their demands for better treatment. By winning the confidence of the workers in this way the communists then hoped to be able to lead them on to an attack on Capitalism.

What was the result? A writer in their official organ tells us:

“The unemployed have done all they can and the Government know it. They have tramped through the rain in endless processions. They have gone in mass deputations to the Guardians. They have attended innumerable meetings and have been told to be ‘solid’. They have marched to London enduring terrible hardships . . . All this has led nowhere. None of the marchers believe that seeing Bonar Law in the flesh will make any difference. Willing for any sacrifice, there seems no outlet, no next step. In weariness and bitter disillusionment the unemployed movement is turning in upon itself. There is sporadic action, local rioting, but not central direction. The Government has signified its exact appreciation of the confusion by arresting Hannington.

The plain truth is that the unemployed can only be organised for agitation, not for action. Effective action is the job of the working class as a whole. The Government is not afraid of starving men so long as the mass of workers look on and keep the ring” (Workers’ Weekly, 10th February, 1923).

Another communist described the way in which discontent will drive men and women into joining associations that promise them immediate benefit, but how easily the membership thus recruited fades away when capitalists give slight concessions. The references are to an unemployed organisation in Liverpool, but are typical of what happened all over the country. The article was published in January, 1923, in The Worker (20th January 1923).

First, the writer tells us that the organisation began in 1921, with a gathering 20,000 strong and a committee “comprised for the most part of Communists”. There was a baton charge by the police in September and most of the committee were arrested. The unemployed then attacked a picture gallery and turned it “into a shambles”.

“From then onwards the number declined, due to the fact that a scale of relief had been granted, and that the spineless ones had got the wind up and left. We managed to keep a crowd of 10,000”.

The article then describes how the unemployed again came into conflict with the police:

“This gave us another setback in point of numbers, and the people left began to show signs of class consciousness . . . They began to flock to the Communist Party. Very few stayed in, but those who left were inoculated with germs of the class struggle. Due to another agitation we were granted the use of another hall. Again, after another couple of months, we got notice to quit. From then onwards until about April or May 1922 the apathy became terrible.

‘The Guardians of the rich’, seeing this, began to get brave by daring to cut the relief down. A few hundred returned and wanted to know what we were going to do . . . try as we would we could not get them to kick . . . In September (1922) they returned again. The Guardians had brought in a system of test work . . . the agitation became strong . . . the test work suddenly stopped, so did the demonstrations of our organisation.”

This communist writer’s last words sum up the whole situation. Writing of the typical unemployed worker, he says:

“The immediate wrongs . . . being satisfied . . . he drifted away again. Thus the movement has declined, and hardly exists to-day outside of a small committee”.

The years 1931 and 1932 have seen the communists—blind to their own experiences—acting this tragic farce over again.

It must be obvious that unstable organisations of this kind, composed of non-socialists, and recruited merely on some minor question of the day, cannot be of use in the striving for Socialism.

In 1926 the communists had an excellent opportunity to try out their theory on the millions of workers who were involved in the strike or were sympathetic towards it. The result was just what we have said it must be. Strikes can serve a useful purpose in resisting wage reductions or securing increases, but they cannot overthrow Capitalism. To begin with, the workers themselves have not that purpose in mind, and even when they become socialists they will still need political organisation in order to capture the real centre of power—the machinery of government and the armed forces controlled by it. This no strike can do.

The strikers wished simply to help the miners. In the main, neither they nor the miners had any wish to overthrow the government or to introduce Socialism. To the extent, therefore, that the communists were able to make known their intention of using the strike to overthrow the State, they were not attracting but repelling the workers. As the communists confessed, the “strikers had no horizon beyond bringing aid to the miners, and thereby resisting the employers’ offensive against themselves” (The Labour Monthly, June 1926, p. 347). The workers had no desire to use the strike for revolutionary ends, and as the outcome showed, the State, with its financial resources, its armed forces, its support in the press, and its prestige with the mass of the population, has nothing to fear from striking workers even when they number two or three millions.

In a large strike, as in a small one, starvation fights on the side of the propertied class against the wage earners. We know from the General Strike, and from revolts of workers attempted in many countries at different times, that desperate men and women will take desperate action when goaded to it by the hardships of their life under Capitalism. But we have seen in the General Strike of 1926 how such spontaneous outbursts are always crushed by the forces at the disposal of the ruling class through their control of the machinery of Government. How much easier it is, and how much less costly in human suffering, to convert a majority to Socialism than to engage in these blind revolts!

There is, too, another factor of great importance. The ruling class usually and in the long run are not blind to their own interests, and do not drive the working class as a whole into revolt. They are not so foolish as to leave only that alternative. By means of charity, doles, and unemployment insurance, and, if need be, the grant of higher wages and other concessions, the capitalists can always take the edge off periods of the more acute industrial depressions.

The problem of “over-production” that is behind every crisis is always relieved in due course for a time. Employers close down production and thus stop the stocks from being added to. Governments tax the employers and with the money so obtained enable the unemployed to buy a certain amount of the accumulation of articles. Capitalists combine, with or without the assistance of Governments, to destroy stocks. At the beginning of 1932, Brazilian coffee was being burned, thrown into the sea, and used for fuel. Wheat was being burned in Canada and U. S. A., and a resolution was passed by the United States Senate recommending that the U. S. A. Government hand over to the unemployed the 40,000,000 bushels of wheat held by the Farm Board. In addition, in site of every care, great stocks of raw materials deteriorate and spoil. As a last resort there is the colossal destruction of wars to relieve pressure. Sooner or later, these crises of over-production have always given place to a resumption of fairly brisk trade and employment, without, of course, abolishing unemployment. Capitalism cannot do that.

Some of the communists have indeed just begun to recognise the unsoundness of their theory. In The Labour Monthly (January 1932), Mr. Dutt quotes with approval a statement of Lenin’s—that no situation for Capitalism is “without a way out”, and says:

“We know that the overthrow of capitalism . . . requires the most titanic and long-drawn struggle, action, organisation, and victory of the working class; and that until this is attained, capitalism will still drag on from crisis to crisis, from hell to greater hell”.

To this we would add that the workers will never be able to take sound action until they possess the knowledge of Socialism that it is our aim to provide. So long as the workers lack a knowledge of socialist principles, and a determination to bring Socialism about, each crisis will pass off in this fashion. As a matter of fact, it is not always true that the additional hardship makes the workers kick, even blindly, against Capitalism. The capitalists are so well able to excite the workers’ fears, because of a lack of socialist knowledge, that we often see the workers in times of crisis rallying round the most openly capitalist and reactionary parties. We saw this in the 1931 crisis, when an overwhelming majority of workers in Great Britain and in Australia voted into power reactionary “Nationalist” parties, in spite of the plans of these parties to reduce unemployment pay and the pay of Government employees, and to impose other economies.

V. THE ONLY ROAD TO SOCIALISM

The lesson to be learned is that there is no simple way out of Capitalism by leaving the system to collapse of its own accord. Until a sufficient number of workers are prepared to organise politically for the conscious purpose of ending Capitalism, that system will stagger on indefinitely

Throughout the 19th century, and up to the present time, many attempts have been made to build up working class organisations on the basis of demanding concessions from the capitalists to meet the evil effects of the capitalist system. There have been numbers of unemployed organisations asking for “work or maintenance” and political parties, such as the Labour Party, the I. L .P., and the Communist Party, seeking support on programmes of reforms. Some of these bodies have obtained a large membership and have appeared to gain small concessions. Some have even taken over the Government and tried to apply their reform programmes. But such organisations do not, and cannot, bring Socialism. Their members are attracted by the promises of immediate results. They are not willing to work for the abolition of Capitalism because they have not learned that it is Capitalism which causes the evils they are seeking to remove. These organisations cannot get beyond the limited aims and understanding of their members. They are built up on a wrong foundation. They are not deserving of working class support. They may reform Capitalism, but they cannot abolish it.

So long as the workers are prepared to resign themselves to the evils of Capitalism, and so long as they are prepared to place in control of Parliament parties that will use their power for the purpose of maintaining Capitalism, there is no escape from the effects of Capitalism. The workers will continue to suffer from the normal hardships of the capitalist system when trade is relatively good, and from the aggravated hardships which are the workers’ lot during trade depressions.

That is the prospect before the workers of all the world unless they actively interest themselves in understanding socialist principles and assisting in socialist organisation.

A PERSONAL APPEAL

We have now stated our case and we hope that you have given it the consideration it deserves. The question is, what are you going to do? Are you going to put it aside and carry on as of yore, or are you going to arm yourselves with socialist knowledge? One way lies poverty, misery and bondage; the other way lies the road to emancipation and, at its end, all the happiness and fullness of life that the gigantic and fruitful machinery of modern industry offers to a world of free and equal men and women. The choice is before you; only knowledge, desire and self-confidence are needed to realise the free society of the future. Place not your trust in others, but be assured that the work there is to do must be done by yourselves.