PDF Version The Market System Must Go!

Introduction

This pamphlet, on the subject of ‘reform or revolution’, is intended to explain why the Socialist Party advocates a revolutionary transformation of existing society rather than piecemeal reform, like the Labour Party or the Conservatives. It is primarily intended to be a detailed back-up to our more introductory pamphlets putting the case for revolutionary change, and to our journal The Socialist Standard.

Much of the material in this pamphlet is new, but some has been adapted from previous editions of our pamphlets, principally the now out-of-print Questions of the Day. The earlier chapters develop the case against reformist politics in general, while later chapters discuss specific subjects of concern to modern reformers, ranging from the welfare state to tax reform. It provides a comprehensive critique of the outlook of those who oppose the politics of democratic socialist revolution in favour of reform activity, and is to be particularly recommended to those who consider that reform intervention can make capitalism run in the interests of the wage and salary-earning working class.

The Socialist Party,

February 1997

1. Society Today – Capitalism

2. Gradualism and Revolution

3. Reforms and the Origins of the Socialist Party

4. The Futility of Reformism

5. The Mythology of the Left

6. Taxation – an issue for the working class?

7. Do the Rich Still Get Richer?

8. The Continuing Trade Cycle

9. The Crumbling Welfare State

10. Inflation – Another Product of Reformism

11. ‘Successful’ Reforms

12. The Socialist Solution

01. Society Today – Capitalism

The type of society we live in today is properly called capitalism. Earlier ways of organising society still exist in some parts of the globe, but capitalism is now dominant across the world. It is a system of society based on the class ownership of the means of production and distribution in which wealth is produced by those who can only live by selling their ability to work for wages and salaries. The wealth they produce is sold on a market with a view to profit by the wealth owners. Capitalism, therefore, is a class society with a privileged few living off the labour of the exploited many. It exists equally in Cuba and China as it does in Britain and the United States.

The basic contradiction of capitalism is between social production and class ownership. The actual work of producing the wealth is done by the co-operative labour of millions, while the means of production and the products belong to a minority section of society only, the capitalists. It is this contradiction that causes modem social problems since it means that production cannot be carried on to meet human needs. Consequently, where such needs conflict with profit-making the needs must come second.

Human needs are only met under capitalism to the extent that they can be paid for. This is no problem to the rich but it is for the working class who have to work for wages and salaries. The working class is composed of the men and women who, excluded from ownership of the means of living, are forced by economic necessity to sell their mental and physical energies to the owning class of capitalists. For the purpose of this definition workers are not distinguished by the way they dress, talk, where they live or the type of job they do, but by how they get their living. Anybody who has to work for wages or a salary to live is a worker In Britain, over 90 per cent of the adult population are workers, retired workers or the dependants of workers.

Since under capitalism workers depend on their wages and salaries in order to live, it is clearly very important to understand what governs the rate of wages. Wages are in fact a price, the price of the mental and physical energies workers sell to employers. They are not a reward for having worked, a share in the product, or even the price of work done. Receiving a pay packet or salary cheque is a buying and selling transaction no different in principle from the sale of a pair of shoes or a car. The price of someone’s ability to work – or as Marx, who first saw this clearly called it, ‘labour power’ – is fixed in much the same way as that of a pair of shoes or a car, roughly by the amount of labour used up in producing and maintaining it. A person’s wage will never in the long run amount to much more than will cover the costs they must incur to keep themselves fit to work, with additions for their family. An engineer with a college degree gets more than an unskilled labourer because it costs more to train and keep the engineer.

The wages system is a form of rationing. It restricts a worker’s consumption to what is needed to keep the worker in efficient working order. It means the workers are generally deprived of the best that is available in food, clothing, housing, entertainment, travel and the like. This is made all the worse because there could, on the basis of modern technology, be plenty of the best for everyone. It is made worse still because it is the working class who produce all the wealth, the best that the rich enjoy as well as the utility items they themselves consume.

That the workers are exploited under capitalism is not hard to grasp. Exploitation does not mean that workers are shackled to the factory production line or the office desk and terrorized by bullying foremen. It simply means that they get as wages less than the value of what they produce. There is no need to go into a complicated economic analysis to prove this. It is sufficient to say that since the only way in which wealth can be produced is by human beings applying their mental and physical energies to materials found in nature, any society in which a few live well without having to work must, on the face of it, be based on the exploitation of those who do work. That this is so under capitalism is clear when the peculiar quality of labour power is understood. Labour power can produce a value greater than its own so that whoever buys it and puts it to use can reap the benefit of this: which is precisely what the capitalist employer does. The capitalist buys labour power for wages, puts the men and women who are selling it to work, in his or her factory with his or her tools and materials, and then realises a surplus when the finished product is sold. The source of this surplus, with its divisions of rent, interest and profit, is the unpaid labour of the workers.

Because capitalism is based on the class ownership of the means of living and the accompanying exploitation of the workers, depriving them of the fruits of their labour, there is an irreconcilable conflict of interest between the working class and the capitalist class. This is the class struggle which goes on all the time over the ownership of the wealth of society. Its obvious features are strikes and lockouts, trade unions and employers’ associations. These are the main weapons and organizations of the two sides in the industrial field. In the political field the capitalists have the government on their side. Their ownership and control of industry rests on their control of political power through their political parties, and as long as this is so the purpose of the government is to preserve the capitalists’ monopoly of the means of wealth production. This is why in the end all governments must take the side of the employers, by protecting their ownership of property, by declaring states of emergency, by using police and troops to break strikes, by imposing pay freezes and by passing anti-trade union legislation. It is also why the workers must organize politically into a socialist party with a policy based on recognition of this class struggle and its irreconcilable nature.

Capitalism is the cause of the social problems that afflict the working class today. Under capitalism the workers are, in the strictest sense, poor – that is, they lack the means to afford the best that is available in society. For instance, people often talk of there being a housing problem, but there is no such problem. There is no reason why good houses for all should not be built. The materials exist, and so do the building workers and architects. What then, stands in the way? The simple fact is that there is not a sizeable market for good houses since most people cannot afford to pay for them, and never will because of the restrictions of the wages system. So what is called the housing problem is really but an aspect of the poverty problem or, what is the same thing – since it is the other side of the coin – the class monopoly of the means of production.

A little thought will show how capitalism, besides ensuring that the workers stay poor, needs them to be poor. If they could get a living without having to sell their mental and physical energies to the capitalists, then the system could not function – for who would do the work? By poor we do not mean destitute, though this is an extreme form of poverty. Certainly, as long as capitalism lasts, there will be a considerable minority of people who cannot stand the pace and so fall into destitution and have to depend on state benefits.

Housing is just one aspect of the poverty problem. The same applies to the other necessities of life like clothing, food, education, travel and entertainment. Here again, in a world of potential plenty the consumption of the workers is restricted by the size of their wage packets and salary cheques.

Capitalism cannot produce primarily to satisfy human needs as production is always geared to meeting market demand at a profit. This means that production is restricted to what people can pay for. But what people can pay for and what they want are two different things, so the profit system acts as a fetter on production and a barrier to a society of abundance. As we shall see, it is also responsible for the business cycle, with its periodic trade depressions.

One thing should be understood about capitalism above all else – it can never be made to run in the interests of the working class. It is based on working class poverty and exploitation and can only work in the interests of the privileged owning class. A recognition of this is one of the guiding principles of the Socialist Party. As we hope to demonstrate further, it can be summed up in the sentence “capitalism cannot be reformed” (at least not to run in the interests of the workers). Grasp this and you can quickly see the futility of tinkering with capitalism and trying to tackle each problem on its own.

To solve their problems the workers must abolish capitalism and replace it with socialism. This will involve a social revolution, changing the basis of society from class to common ownership of the means of living. When society owns and democratically controls the means of life then men and women can begin to organise production to satisfy their needs and desires. Production solely for use can replace the anti-social principle of production for profit. Exploitation will be ended and a world of abundance made possible.

To many, the word ‘revolution’ conjures up visions of barricades and public executions. All it really means is a complete change, without any implication as to how that change is to come about. The Socialist Party stands for a revolution in the basis of society, a complete change from class to common ownership of the means of living: this social revolution to be carried out democratically by the use of political power. It is possible for a majority of socialists to win power through democratic institutions, by use of the ballot, for the purpose of carrying out the socialist revolution. Thus we stand for democratic revolutionary political action.

In the past, and to a lesser extent today, others who claimed to stand for socialism advocated what they thought was an alternative method: by working, under capitalism, to induce the government to enact reform measures favourable to workers. They stood for reformist political action which they hoped would gradually transform capitalism into socialism without the need for class conscious workers’ political action. This policy was called gradualism.

In Britain the leading gradualist thinkers were in the Fabian Society, formed in 1884. The Fabians held that by ‘permeating’ the civil service together with the working class and ‘middle class’ organisations they could gradually change society. Their real aim was state-run capitalism in which they saw themselves as the most suitable top administrators. Gradualism, as expounded by the Fabians and adopted by the Labour Party, has always been the dominant reformist theory in Britain. Labour leaders have always rejected the Marxian analysis and never even claimed to be revolutionary.

The situation was different on the continent, and especially in Germany, where there were large parties, supported by millions of workers, claiming to be Marxist and to stand for a revolutionary policy. The German Social Democratic Party was the largest and most influential of these parties; but at the turn of the century it was rent by a controversy over gradualism which became known as the ‘revisionist’ debate.

Eduard Bernstein, a close friend of Marx’s collaborator Engels, spent many years in exile in London and came under the influence of Fabian thinking. He attacked the main tenets of Marxism and called upon the German SPD to recognise that it was in reality only a reform party. He suggested that they be honest with themselves and drop their ultimate commitment to the capture of power for socialism and instead concentrate on getting reforms within capitalism by working through Parliament and co-operatives, the trade unions and local councils, and even by co-operating with non-socialist parties.

Bernstein and his supporters were answered and refuted by the arguments of men like Karl Kautsky who generally had a better grasp of Marx’s writings and who did a great deal to popularise them. The German Social Democratic Party formally turned down Bernstein’s suggestions but the decision meant nothing as far as the Party’s practical policy was concerned. They retained their paper commitment to the socialist revolution but continued their day-to-day reformist practices. For it was on the basis of reforms and not socialism that their support among the German workers rested. In time, as their attitude to the First World War was dramatically to show, they became bogged down in reformist politics and prisoners of their non-socialist and patriotic supporters so that they lost all claim to be called a socialist party. Even opponents of revisionism like Kautsky were ready to defend the idea that a socialist party could engage in reform politics. Like the gradualists, they also had some odd views about socialism, usually equating it with nationalisation by a democratic state and holding that the wages system and buying and selling were quite compatible with the common ownership of the means of production. Their ultimate aim, like that of the Fabians, was state capitalism – not socialism.

The question of reform or revolution was discussed not only in Germany but throughout Europe and America. In the English-speaking world parties with socialism supposedly as their aim had failed to attract mass support even for reforms. This had the advantage of allowing them the chance to look at the issue in an objective manner since they did not have to worry so much how their answer might offend their non-socialist supporters. One important view to emerge was that the way to avoid the dangers of reformism was for a socialist party to seek support for socialism alone and not to campaign for so-called immediate demands within capitalism. This view was held by some members of the Socialist Party of Canada, the Socialist Party of America and the Socialist Labour Party of America. In Britain it was advocated within the Social Democratic Federation by a group which in 1904 left to set up the Socialist Party of Great Britain.

That a socialist party should not advocate reforms has always been the policy of the Socialist Party of Great Britain and our companion parties abroad who together make up the World Socialist Movement. This is not to say that reforms can never bring any benefit to the workers. As we shall see, some can and do, while many are futile or harmful. But a socialist party which advocates reforms would attract the support of people interested more in these reforms than in socialism. In these circumstances the party would be dragged into compromise with capitalism and so in the end become merely another reform party even if it still proclaimed socialism as its ultimate aim. As socialism can only be achieved when a majority of workers understand and want it, a socialist party must build up support for this aim alone. Support gained on any other basis is quite useless, even harmful.

Despite the existence there of large Social Democratic parties, mainland Europe was both socially and politically less advanced than Britain (where capitalism had long eliminated the peasant class) and North America (which had never known feudalism). In Europe significant remnants of feudalism survived; the workers there were only a minority amidst a population of peasants, artisans and small traders; many still thought of revolution in terms of a determined band of conspirators setting up barricades in a bid to seize important civic buildings much as had happened in France in 1830, in many other European cities in 1848 and in Italy in the 1860s.

This tradition put many of the European opponents of reformism on the wrong track. They mistakenly argued that it was parliamentary politics that had led the Social Democratic parties astray and that political power for socialism could only be won through an armed uprising. Thus the reform and revolution controversy tended to resolve itself into Parliament versus insurrection, in which both sides assumed that democratic, Parliamentary action must be reformist.

As capitalism developed, insurrection as a way to political power became more and more obviously outmoded. The advocates of Parliamentary action, even though reformist, were able effectively to refute the ideas associated with armed uprisings. Later many of the supporters of armed uprisings, especially under the influence of Russian Bolshevism, went from bad to worse and agitated for minority coups of the kind opposed by Marx and Engels as far back as 1848. Following the Bolshevik lead, they were able to establish many state capitalist dictatorships across the world on this basis, but never socialism. Thus the principal opponents of reformism ended up in a blind alley, eventually to capitulate to reformism themselves, as we shall see in Chapter Five.

One of the Socialist Party of Great Britain’s primary contributions to the development of socialist theory lies in having worked out a satisfactory solution to the problem of reform or revolution based on the revolutionary use of democratic institutions to achieve socialism. The ballot had only been used by the orthodox Social Democrats to get reforms and it was assumed that this was the only purpose for which it could be used. We pointed out that this was a false conclusion and that there was no reason why Parliament and councils could not be used by a class-conscious socialist majority to win power and dispossess the capitalist class.

The two futile policies of insurrection and reformism can be avoided by building up a socialist party composed of and supported by convinced socialists only. When a majority of workers are socialist-minded and organised in a socialist political party, they can use their votes to elect to Parliament and the local councils delegates pledged to use political power for the one revolutionary act of converting the means of living into the common property of humankind. Socialists will be organised on the economic front too, to ensure the continuation of production in socialism, but history has demonstrated that the capture of political power is essential if a successful revolution is to be carried out as peacefully and democratically as possible.

Minority insurrection could never lead to socialism and has never represented a real alternative to the dead-end of reformism. Only a majority of workers organised to dispossess the capitalists of their power base in the state machine and their democratic legitimacy are likely to achieve a society of common ownership and production for use. Hence the real choice that lies in front of the workers today – more social reforms or worldwide democratic socialist revolution.

3. Reforms and the Origins of the Socialist Party

The Socialist Party of Great Britain, which is the only party in this country to stand for democratic socialist revolution, was formed on 12 June 1904 by around one hundred and forty members and former members of the Social Democratic Federation who were dissatisfied with the policy and structure of that organisation.

The SDF had been formed in 1883 as a professed Marxist party, although Engels, who was living in London at the time, would have nothing to do with it. At that time the writings of Marx, Engels and other socialist pioneers were hardly known in the English-speaking countries, except to the few who knew foreign languages. The SDF, however, did have the merit of popularising in Britain the ideas and works of Marx. This was later to bear fruit in demands for an uncompromising, democratically organised socialist party in place of the reformist and undemocratic SDF.

Although it claimed a socialist objective, the SDF spent much of its time campaigning for reforms that were supposed to improve working class conditions within capitalism. Its reform programme contained a long series of demands ranging from proposals for a heavily graduated system of income tax, to universal education for children and Home Rule for Ireland.

Henry M. Hyndman, who played the major role in setting up the Federation, seemed to regard it as his personal possession and reacted to any criticism in an autocratic manner. The Federation journal, Justice, was owned by a private group over which the members had no control.

The opportunism and arrogance of Hyndman had already led to a break-away in 1884 when a number of members, including William Morris and Eleanor Marx, set up the Socialist League which was more democratically organised and which didn’t campaign for reforms. However, after a short while the Socialist League ceased to be of use as it became dominated by anarchists who rejected majority political action.

A second revolt from the SDF led to the formation in 1903 of the Socialist Labour Party, copying the American organisation of that name. At first, along with a programme of immediate reform demands (which were later abandoned) the SLP declared its object to be the conquest of political power, but soon, under the influence of its American parent, it subordinated political to industrial action.

Another revolt against the Hyndman group’s dominance of the SDF was organised by men and women who had a much firmer grasp of Marxian political and economic theory. For their opposition to opportunism and reformism they were contemptuously called ‘impossibilists’. At first they tried to use the machinery of the SDF to get the party to change direction, but they came up against the Hyndman clique who were ready to resort to all kinds of undemocratic practices to maintain their control of the party. Conferences were packed, branches dissolved and members expelled.

Matters came to a head at the 1904 SDF Conference held in Burnley at the beginning of April. At the Conference more expulsions took place. When the delegates of some of the London branches returned they held a special meeting to discuss the situation and approved a statement which, among other things, urged the following:

“The adoption of an uncompromising attitude which admits of no arrangements with any section of the capitalist party; nor permits any compromise with any individual or party not recognising the class war as a basic principle, and not prepared to work for the overthrow of the present, capitalist system. Opposition to all who are not openly and avowedly working for the realisation of Social Democracy. A remodelled organisation, wherein the executive shall be mainly an administrative body, the policy and tactics to be determined and controlled by the entire organisation. The Party Organ to be owned, controlled and run by the party. The individual member to have the right to claim protection of the whole organisation against tyrannical decisions.”

On 12 June most of those who signed this leaflet, together with a few others, founded the Socialist Party of Great Britain.

The constitution of the Socialist Party was framed in such a manner that what had happened in the SDF would be impossible. The Executive Committee, elected by the whole of the membership, was to run the day-to-day affairs of the Party in accordance with the policy laid down at Conferences and was required to report to the membership twice a year. All its meetings were to be open not only to members but also to non-members. The Party journal, The Socialist Standard, which first appeared in September 1904 and monthly ever since, is under Party control through the Executive Committee. An elaborate appeals procedure – first to the Conference or Delegate Meeting and then to a poll of all the members – was written into the rulebook to protect any member charged with activities warranting expulsion.

The rulebook of the Socialist Party lays down a thoroughly democratic procedure for the conduct of Party affairs. Control of policy is in the hands of the members; there are no leaders and never have been. Democratic procedure has been maintained throughout the Party’s existence and is a practical refutation of those who argue that all organisations must degenerate into bureaucratic rule. In fact, a democratic structure without leaders is the necessary form of any real socialist party.

At its formation the members of the Socialist Party adopted an Object and Declaration of Principles which, without the need for any change, has remained the basis of membership of the Party. Within that framework the Party has worked consistently to make socialist principles known and to expose the many erroneous and dangerous theories that have attracted support among the working class – foremost among them being the notion that capitalism can be reformed to run in the interests of the workers.

Many people have sympathy with the socialist idea of a world of common ownership and free access to replace the present system of buying and selling, but say that such a transformation is a long way off and that in the meantime we must still aim for improvements within the framework of the existing system. They point to the changes that have taken place in people’s lives since the nineteenth century. They point to the fact that in countries like Britain children no longer run around without shoes on their feet, no-one starves, medical facilities are available to all, everybody receives an education, and many people own things previously undreamed of – a car, a house perhaps, and a host of electrical gadgets. It is worth trying to get more of these improvements, they say, and the best way to do it is to press governments for reforms.

Legislative reforms may have helped to improve the conditions of life for wage and salary earners, but the main factor in this has been the struggle of workers in trade unions to gain pay increases and improved conditions. Before considering whether it is worth working for reforms, the question it is relevant to ask is why do governments bring them in? Is it through concern for people’s well-being? Is it through pressure from groups of committed people outside Parliament? Is it through a combination of the two? Or is it for some other reason?

It may at first sight seem that certain reforms are motivated by humanitarian concern on the part of governments. The ‘welfare state’ legislation, for example, brought in after World War Two, provided state pensions and medical treatment for almost the whole population. It may seem that public agitation for reforms also does a lot to help, as when abortion was legalised in 1967 after many years of campaigning by members of the Abortion Law Reform Association.

Yet if we look closely at the mass of laws governments have passed over the years, we find not only measures which seem to have a humane motive, but others which are just the opposite. Labour’s 1965 and 1969 Immigration Acts, for example, caused heartbreak for many would-be Commonwealth immigrants including some with British passports, while in 1980 some of the poorest among Britain’s population were made poorer still by a Conservative Social Security Act which cut benefits for unemployed people and invalidity pensioners by five per cent. And if we look closely at the history of reform legislation, we find that sometimes governments seem to take notice of relatively small-scale campaigns (such as with the 1967 law change on homosexuality) while at other times very large reform movements – such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament – produce no alteration in government policy at all.

Why then do some of the reforms governments bring in seem to mark social progress while others are clearly backward and oppressive? Why does a government appear on one issue to listen to appeals from reform campaigners and on another to be completely deaf to them? The answer to these questions is that the attitude of governments does not depend on the good-heartedness or otherwise of particular parties or politicians, or on the special ability of any particular pressure group outside parliament to influence them. The answer lies in an understanding of the function of governments.

Governments are not there to solve the problems of those who elect them. Nor are they impartial. Governments are there to administer in the most smooth and efficient way possible a system whose whole economic mechanism is governed by the search for profits. Priority has to be given to profits since they are, as it were, its lifeblood. The single-minded pursuit of profit is the system’s economic logic, the driving force of capital, and imposes itself on governments whether they like it or not. Governments can try to resist it – as some have done for a short while – but in the end they are forced to accept the logic of the system that puts profits first. The capital and the profits are owned by that small class of people who possess the land, the factories, farms, offices and communications systems – society’s means of living. Governments, therefore, exist to serve the interests of this minority class.

It follows that all reforms are brought forward within the economic limitations of capitalism and generally have the aim of creating the best conditions possible for profits to be made. They cannot allow the interests of the wage and salary earners to obstruct this. This explains why a government can pass some laws that are unambiguously detrimental to workers’ interests and others that are of some benefit. The point is that any benefit is always incidental, never central, to a law’s purpose.

This also explains the seemingly inconsistent attitude of governments to pressure from reform campaigners. If a campaign is proposing a certain reform that happens to be in line with, or at least not contrary to, a government’s own plans for administering the capitalist system, the government will not be averse to lending an ear and indeed not be particularly upset if the campaign takes credit for any legislation passed. Campaigns are, in fact, sometimes whipped up by governments themselves to gain support for unpopular, but from the point of view of a section of the capitalist class, essential measures, as for example the Labour Party’s campaign in the 1975 referendum to get people to vote ‘yes’ to staying in what was then the EEC. If, however, a campaign is out of line with the profit- making needs of the system, then no amount of protest or public pressure has any effect. The recent campaign against nuclear weapons was doomed to failure because it ignored the fact that the British government, like others, has to have at its disposal the most up-to-date weapons available to protect the interests of the British owning class in potential disputes, and deter foreign owning classes from interfering with the power structures, markets, trade routes and sources of raw materials which are essential to the continued making of profits.

In the same way a well-intentioned organisation like Shelter cannot succeed in its aim of obtaining decent housing for everyone. The housing problem could of course be solved tomorrow if production were allowed to be carried on simply to satisfy human needs. What prevents it is the rigidity of the economic system that insists that profits must be made out of producing things. As there is no profit to be made in producing decent houses for people who cannot afford them, a government cannot pass laws ordering houses to be built for them without making someone pay the bill.

This is not to say that governments can never be influenced by protest campaigns. The outcry in the trade union movement in 1969 caused the Labour government to drop its plan to introduce an Industrial Relations Act (‘In Place of Strife’) and the campaign by Welsh nationalists in 1980 persuaded the Tories to keep their election promise to set up a television channel in Welsh (S4C). Similarly, in the early 1990s the campaign against the Community Charge (‘Poll Tax’) helped get that tax replaced by another, although in this instance the campaigners were helped by the gross inefficiency of the Poll Tax as well as by popular discontent.

Despite the hopes of reform campaigners everywhere, governments will only bend to such pressure on issues of either minor importance or which are causing them social, political or financial problems. They are not, as many people think, free agents who can do whatever they want. They operate within a definite economic and social framework that severely limits their options.

Governments – all governments – must constantly bring in reforms. The continuously changing industrial, economic and social situation produced by the system’s dynamic, competitive nature dictates this. These reforms, however, must be broadly in line with the overall interests of the owning, profit-making minority. Let us take a few examples from the history of reform legislation to see how this has operated.

The 1870 Education Act, supported by both Liberals and Tories in Parliament, began the process whereby basic educational facilities were to be provided by the state for all children regardless of their parents’ means. This was not done, however, with the idea that workers’ children should as of right have a decent education, but to ensure the turning out of more literate, better trained workers for an industrial society that was becoming increasingly complex.

The first modern-style social security legislation was brought in by the Liberals with the introduction of the Old Age Pensions Act of 1908 when pensions started to be paid to the state to some over-seventies. Here the government was not acting out of compassion for old people suffering poverty, but was following up a Cabinet paper of December 1906 which pointed out that pensions for the old would mean large savings in Poor Law costs.

The introduction of the ‘welfare state’ in Britain under a Labour government after the Second World War brought in a comprehensive system of ‘free’ health care, unemployment benefits, state pensions and family allowances. However, contrary to popular belief, this legislation was not wanted for humanitarian reasons. It resulted from the realisation by politicians and industrialists that an all-embracing scheme of social security would be cheaper to run than the existing piecemeal system and, above all, that healthier, more contented workers would make a more efficient, and therefore cheaper, labour force. Sir William Beveridge, who drew up the original plan, constantly argued in his Report that his proposals would be more economical to administer than previous methods, and in February 1943 Samuel Courtauld, millionaire Tory industrialist, said of the Report: “Social security of this nature will be about the most profitable long-term investment the country could make. It will not undermine the morale of the nations’ workers: it will ultimately lead to higher efficiency among them and a lowering of production costs” (Manchester Guardian, 19 February 1943). Most other employers were apparently of the same opinion, for in a poll conducted at the time, 75 per cent of them agreed that the Beveridge Report should be adopted (Susanne MacGregor, The Politics of Poverty, p.21.)

In 1956 the Clean Air Act, brought in by the Tories, introduced smokeless zones and got rid of London’s smog. But the Act’s driving force was not the desire that people should have a clean environment to live and work in, but the findings of the government Beaver Committee that the cost of pollution to Britain (and therefore a loss in profits) was in the order of £250 million annually, then a huge sum.

The 1969 Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act, a Labour Private Member’s Bill which gained all-party support, had provision for services and facilities to improve living conditions for disabled people. But, even in this case, the expense had to be justified on economic grounds: its sponsor, Alf Morris MP, stressed the saving that would result from providing disabled people with facilities to live at home rather than institutionalising them.

It should be clear to everyone that all the political parties that have held office are reforming parties. No one party, ‘left’ or ‘right’, holds a monopoly on reforms. Although the Labour Party has always posed as the champion of reforms and is thought of as such by many people, reforms which have been of some apparent benefit to workers have no less often been brought in by Liberal and Conservative governments. Even the set of reforms the Labour Party is fond of parading as its showpiece, the ‘welfare state’, was accepted in principle by the wartime coalition of Liberal, Labour and Tory parties. Its first stage, the 1945 Family Allowances Act, was a measure agreed by the Coalition government and actually became law during the short Conservative ministry of May-July 1945.

Furthermore, when the needs of the system have dictated it, Labour has shown itself to be just as ruthless as the other parties in introducing reforms that have been openly harmful to the working class. Its National Health Service Amendment Act of 1949 provided for a charge for prescriptions from family doctors, and in 1951 it introduced charges for dentures and spectacles. This was after Aneurin Bevan, Labour Health Minister, had already stated in a press conference that the government had ‘set its face against’ the whole idea of NHS charges. Labour’s 1964-70 measures included a wage freeze, increases in prescription charges, the abolition of free milk in secondary schools and the ‘four-week rule’ under which any single unskilled worker under the age of 45 would be granted supplementary benefit for only four weeks if work was considered to be available in the area. In 1977 a Labour government again cut back on the National Health Service and also made drastic cuts in resources allocated to education.

The claims of the Labour Party to be the reforming party par excellence are simply not backed up by experience. Nor, given the nature of the system it commits itself to administer, can this be any different in the future. Whatever the levels of state benefits may be, the overall income of workers in real terms tends to adjust to the amount necessary to maintain themselves as workers and to bring up their children in a similar condition. And if any further evidence of this is needed, we need only look at the total failure of Labour’s counterparts abroad – in France under Mitterrand, Australia under Hawke and Keating, and in Clinton’s America, to name but a few. All these administrations with great reforming intentions were able to do was run the system according to its own economic logic – profits first, wage and salary workers a poor second.

There cannot be such a thing as a humane reforming party. Moreover, even when reforms of incidental benefit to workers are brought in, in practice they often turn out to be less beneficial than people expect. Labour’s post-war nationalisation reforms are in a case in point. Many people had great hopes for nationalisation. These hopes were reflected by Will Paynter of the National Union of Mineworkers in his book British Trade Unions and the Problems of Change, where nationalisation was referred to as “the dawn of a new era” in which “workers were moving forward to the control of their own destinies”. But it quickly became clear to people that neither ‘public ownership’ of the nationalised industries nor working in them made any fundamental difference at all to their conditions of life or work. Paynter, who had been secretary of the NUM, realised this and went on to say “The relationship between management and workers remained the same; the union still had to fight hard to get improvements in wages and conditions and little in the daily lives of the men reflected the change that had taken place”.

Another example is Labour’s 1965 Rent Act. It was widely thought that the setting up of tribunals to allow appeals against rent charges would lead to a lower level of rents. Its effect was the opposite. Many landlords applied for increases while few tenants applied for reductions. The reason for this was that to apply for a reduction was likely to be the equivalent of signing one’s own eviction notice.

There are many examples from capitalist history of reforms that promised much but delivered little. Indeed, the very nature of capitalism and the conflicting interests within it make the outcome of reform legislation uncertain and unpredictable, however well-intentioned it may be. Governments constantly need to revise and modify reforms to fit in with new circumstances that they did not or could not foresee. In the long run only those measures that ‘pay their way’ in the sense of maintaining or increasing the productive efficiency of the workforce, are useful to the system. If, either through miscalculation or changed circumstances, a reform turns out to be over-generous then the situation is sooner or later corrected by the reform being drastically cut back or whittled away. In recent years we have seen many examples of this in countries the world over – in health, education, social security, transport and other fields too. The expenditures of the state have become too burdensome for the profitable sectors of industry to carry, so changes have had to be made. Funds have been cut, privatisation introduced and commercialisation pursued in essential services.

The question the reformers of all parties must consider is, after decades of activity, was all their reform campaigning really worth it? And today, is there any point in spending so much time running fast to simply stand still? Socialists unequivocally answer no – it need not be like this. A democratic socialist revolution can sweep away the need for constant reform activity, its stresses and its failures. Socialists know that the work of patching up capitalism will never be done, so why waste time and energy embarking on an impossible mission?

Many political groups, somewhat disenchanted with orthodox reformist practice, fancy themselves as ‘vanguards’ of the working class. We do not. We say that workers should reject these would-be elites and organise for socialism democratically, without leaders.

By fostering wrong ideas about what socialism is and how it can be achieved the vanguard organisations are delaying the socialist revolution. It may help to clear away confusion if we list a number of doctrines held by most of these groups, and then state why we disagree with them:

1.State ownership is socialism, or a step on the way to socialism.

2.Russia set out on the way to socialism.

3. Socialism will arrive by violent insurrection.

4. Workers cannot attain socialist consciousness by their own efforts, only a trade union consciousness.

5. Workers must vote for the Labour Party.

6. Workers must be led by an elite – a ‘vanguard’.

7. Workers must be offered bait to follow this vanguard in the form of ‘transitional demands’, a selective programme of reforms.

It is easy to see how these beliefs interlock and support each other. If, for example, workers are so feeble-minded that they cannot understand socialist arguments then they need to be led. Socialism will therefore come about without mass understanding, by a disciplined minority seizing power. Widespread socialist education is not only unnecessary, it is pointless. If the best workers can do is reach a trade union consciousness and vote Labour, then this is what they must be urged to do. Since workers must have some incentive to follow the vanguard, ‘transitional demands’ in the form of reformist promises are necessary, and since these tactics were successful in carrying to power the Russian Bolsheviks, it is assumed that Russia must have set out on the road to socialism. The basic dogma on which all this is founded is that the mass of the workers cannot understand socialism.

Vanguardists may protest at this summary, they may insist that they are very much concerned with working class consciousness, and do not assert that workers cannot understand socialist politics. However, an examination of their propaganda reveals that ‘consciousness’ means merely following the right leaders. When it is suggested that the majority of the working class must attain a clear desire for the abolition of the wages system, and the introduction of a world-wide moneyless community, the vanguardists reply that this is “too abstract”, or (if they are students) “too academic”. Indeed, they themselves do not strive for such a socialist system. None of the vanguard groups advocate the immediate establishment of a world without wages, with production democratically geared to meeting people’s needs. Some of them say, when pushed, that they look forward to such a world “ultimately”, but since this “ultimate” aim has no effect on their actions it can only be interpreted as an empty platitude. Far from specifying socialism as their aim, they are reticent and muddled about even the capitalist reforms they will introduce if they get power.

Ironically, Bernstein’s dictum “The movement is everything, the goal nothing” sums up the vanguard outlook very well, as a cursory glance at Militant or Socialist Worker will confirm. It seems fair to conclude, however, that the vanguardists’ ideal is the brutal state capitalist regime that existed in Russia under Lenin, a fact which causes us socialists some concern, as it means we would be liquidated (a fate which would undoubtedly have befallen us under the Bolshevik tyranny).

State ownership is not, of course, socialism, but a major feature of all forms of capitalism. It means merely that the capitalist state takes over responsibility for running an industry and exploiting its workers for profit. However wage-slavery is administered it cannot be made to run in the interests of the wage-slaves.

The Labour Party, which receives the support of most of the vanguardists, is not socialist and never was meant to be. Every time it has been in power it has administered capitalism in the only way it can be, as a profit-making system organised in the interest of the profit-takers (the capitalists) and not the profit-makers (the workers). The vanguardists are fully aware of this but their proposition that workers cannot understand socialism commits them to the view that the only way workers will come to see that Labour is no good is through personally experiencing the failure of a Labour government to further working class interests. So, they tell workers to vote Labour. Some even join the Labour Party themselves.

This is an intellectually arrogant view, which sees workers as dumb creatures that only learn by immediate experience without being able to draw on the past experience transmitted to them by other workers. The thinking behind it is that when the workers see the Labour leaders fail them they will then turn to the vanguard for leadership instead. This has never actually happened – not after 1945, nor after 1964, nor after 1974 – and, fortunately (since experience of rule by a vanguard party is one experience workers can certainly do without), probably never will. Some workers do indeed learn by such experiences, but the vanguardists never do. They go on repeating their slogan “Vote Labour” in election after election. Their mistaken view of the intellectual capabilities of workers leads them to urge workers to vote against their interests by supporting one particular party of capitalism in preference to its rivals. The Labour leaders are happy with this and so, no doubt, are other supporters of capitalism who realise that the vanguardists merely channel working class discontent away from a really revolutionary course.

It is the same with ‘transitional demands’, which are just promises to reform capitalism. Workers are urged to struggle for these under the leadership of the vanguard party in the expectation that when these reforms fail to materialise or fail to work (as the vanguard know will happen) the workers will turn against the present system. There again, because of their flawed basic position that workers are incapable of understanding socialism, the vanguardists reject the direct approach of presenting workers with the mass of evidence that reforms don’t solve problems and at best can only patch them up temporarily, and again seek to manipulate workers into personally going through the experience of failure.

Workers don’t need to go down any more blind alleys. The vanguardists, however, don’t agree. They say workers should go down every blind alley they come across until they learn in the only way they supposedly can – direct personal experience of the futility of reformism. And they appoint themselves to lead workers down these blind alleys.

The vanguardists often justify their reformist actions by saying it is a practice known as “developing consciousness through struggle”. “Struggle” is apparently a sort of metaphysical driving force which is supposed to turn reforms into sparks of revolution. Such mystification is essential to the curious doctrine that the workers will establish socialism inadvertently, while they are occupied with something else. But the effect of this is to encourage reformist illusions among the workers, and in fact, since all the main capitalist political parties including Labour now recognise the limits that capitalism imposes on improving living standards, the vanguardists have ended up as the main advocates of reformism today. Look again at the misnamed Socialist Worker or any other Leninist paper and you will see that they spend all their time proposing this measure or opposing that measure within capitalism and none educating workers in the basic principles of socialism. Since they don’t believe the workers can understand these principles anyway they are at least being consistent; as from their point of view to campaign for socialism is to cast pearls before swine. But once again the effect of their mistaken ‘tactic’ is to keep capitalism going.

The belief that socialism or something like it used to exist in Russia is common to most vanguard groups. This is to be expected: the vanguard strategy has been put into practice many times, and should surely have succeeded once or twice. Russia, from Lenin to Gorbachev, furnished fresh proof every day of class privilege and working class poverty that was typically capitalist, but all its obviously anti-working class features were dismissed as the results of ‘degeneration’. Some looked to China or Cuba as less degenerate systems. Some still do. Some even look to North Korea.

Others are not so stupid. They are the vanguardists who have come round to the view that Russia was capitalist, but even they still cling to the idea that the Bolshevik revolution was socialist – and, by implication, that a future socialist revolution will be run on similar lines. After all, an admission that the Russian working class never held political power, and that Bolshevism was always a movement for capitalism, would call into question the entire mythology of the left. A topic of serious concern for vanguardists, if no-one else, is the question: when did ‘degeneration’ start? In truth, more clues to the answer with be found with Robespierre, Tkachev and Lenin than with Stalin.

The belief that Russia was socialist or a “workers’ state” has been a source of confusion for many decades now. Happily, it is ebbing away – illusions are usually corrected by material reality sooner or later. But the fact that such a doctrine could catch on so readily shows the hazy conception of socialism that has always been popular amongst vanguardists. Disputes about how to get socialism usually turn out to be disputes about what it is. For instance, it is apparent that if socialism is to be a democratic society a majority of the population must opt for it before it can come into existence. Any minority which intends to impose what it calls “socialism” on the rest of the population against their wishes or, for that matter, without their express consent, obviously intends to rule undemocratically. A minority which uses violence to get power must use violence to retain power. The means cannot be divorced from the ends.

Vanguardism often emerges in the minds of people who know that there is a lot wrong with society and aim at something radically different. But they avoid facing up to the unfortunate fact that at the moment the great majority of workers do not want a fundamental change. Workers grumble and desire palliatives (or these days desire that things don’t get any worse) but they don’t seek the end of institutions like the police, the armed forces, nor even the Queen, let alone class ownership, the wages system, money and frontiers – the abolition of which is necessary for socialism. It is this refusal to face squarely that the bulk of the working class still accepts capitalism which leads to notions of elitism and insurrectionary violence, to the idea that workers must be manipulated by slogan-shouting demagogues brandishing reformist bait. Discussion, the most potent means of changing attitudes, is treated with contempt. ‘Action’ for its own sake is lauded to the skies.

We socialists have never tried to forget the obvious fact that the working class does not yet want socialism, but we are encouraged by the knowledge that we, as members of the working class, have reacted to capitalism by opposing it. There is nothing remarkable about us as individuals, so it cannot be a hopeless task to set about changing the ideas of our fellow workers – especially as they learn from their own experience of capitalism. How much closer we would be to socialism today if all those who spend their time advocating ‘transitional demands’ were on our side!

Marx’s (and the Socialist Party’s) conception of the working class as all those who have to sell their labour power, from road sweepers to computer programmers, is inconvenient to members of vanguard groups, who often believe that they themselves are not members of the working class, whilst admitting that it is the working class which must achieve socialism. “The workers” cannot grasp anything so “abstract” as socialism, it is claimed. But the exponents of vanguardism do understand it, or so they say. Evidently then, they are not workers: they are the ‘intelligentsia’ or ‘middle class’. They constitute the officer corps. The workers are the instrument, but they wield the instrument. Socialism is a paper hoop through which the working class, performing circus animals, must be coaxed to jump. They are the ringmasters. Or, as their hero Trotsky saw it, the masses are the steam, and the leadership is the piston which gives the steam direction. This notion that they are not members of the working class explains why these people sometimes say to socialists: “What are you doing to get in among the working class?” The socialist worker who is only too chronically and daily aware that they are in and of the working class finds such idealism baffling but entirely consistent with the general confusion exhibited by reform-peddling leaders everywhere.

6. Taxation – an issue for the working class?

When capitalist political parties are in disagreement, the issue of taxation often looms large. Should income tax be reduced or increased? What should be done about local government taxation? What about VAT? These are the type of questions with which the Conservative Party, Labour and the Liberal Democrats are concerned year after year, in Budget after Budget, and election after election. And you can be certain that if an issue is on their agenda they will try hard to ensure it is on the agenda of the working class too.

Why all the fuss about taxation – is it so important? To begin with it is worth looking at why we have taxes in the first place. Taxes are levied by the government in order to raise revenue for the state. The vast bulk of state revenue comes from taxation or borrowing, and as the complexity and functions of the state machine have grown enormously throughout the history of capitalism, so has the tax burden.

The state originally arose out of the division of society into classes, being an instrument for the domination of one class over another. In the present era, the state is controlled by the capitalist class and their political representatives who need to levy tax to pay for the police, the armed forces, civil service, the ‘education’ system and so on. The various functions of the state machine are necessary if the capitalist class are to maintain their privileged position in society, and, of course, these functions have to be paid for by somebody.

That the state is a coercive mechanism designed to perpetuate the class rule of a tiny minority in society is not acknowledged by the capitalists, who present an image of the state as a ‘neutral’ agency standing above society, before which all are equal, and to which all contribute. State revenue is the ‘public purse’, which we all have to support through taxation.

Since our foundation, the Socialist Party has argued against the idea that the state is a ‘neutral’ body, and against the idea that taxation is an issue that should be of concern to the working class. Our argument is that although some taxes are paid by the working class, the burden of taxation rests on the capitalists and has to be paid out of the surplus value accruing to them in the form of rent, interest and profit, the basis of which is the unpaid labour of the working class. To understand this it is worth remembering the nature of the wages and salaries received by the working class.

Wages are the price of the commodity labour power – that is, the price received by workers selling their mental and physical energies to an employer. Labour power is a commodity like so many other things in capitalist society, and its price is governed by the type of factors governing the prices of other commodities – principally the amount needed to produce and reproduce it. In the case of labour power, this includes clothing, housing, food, entertainment and the like. On average, wages are enough to keep us fit to work in the type of employment we have been trained for and are working in and it is around this level that market forces, helped by trade union action, tend to establish wage rates.

It is obvious that the real price of labour power is what is actually received and is not a hypothetical sum, a large part of which is never received by the worker and therefore cannot be spent. In recent years the Conservative Party in particular has argued that if income tax is reduced “we will all be better off”. However, this is incorrect and can be demonstrated to be so with a simple example. Say a worker’s nominal wages are £200 a week, £50 of which is taken in income tax. If the income tax rate was halved and the amount taken in tax was reduced from £50 to £25, then Conservatives would presumably argue this would lead to a rise in the worker’s take home wages from £150 to £175, thereby making him or her “better off”. But this is not what will happen in reality. The workers wage, remember, is the price of his or her labour power, which, all other things being equal, will tend to gravitate around the £150 mark, which is the real sum received all along. The ‘benefit’ from the tax cut goes to the employer. If the situation was reversed and the income tax rate was doubled, the ‘nominal’ wage would then have to rise from £200 to £250 if take home pay was to remain around £150. The increase in this case would be borne entirely by the employer and would come out of surplus value. Of course, this will not happen automatically, but as a result of an economic tendency for the working class to receive the value of its labour power. This tendency is helped by trade union action.

The concept of how tax increases lead to increased nominal wages that cut into profits was rather better understood in the past than it is now. Here, for instance, is what the capitalist and MP David Ricardo wrote in 1817:

“Taxes on wages will raise wages, and therefore will diminish the rate of the profits of stock … a tax on wages is wholly a tax on profits; a tax on necessaries is partly a tax on profits and partly a tax on rich consumers. The ultimate effects which will result from such taxes, then, are precisely the same as those which result from a direct tax on profits” (The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, P.140)

The view that taxes are a burden on the capitalists and not the workers was also put by Marx:

“If all taxes which bear on the working class were abolished root and branch, the necessary consequence would be the reduction of wages by the whole amount of taxes which goes into them. Either the employers’ profit would rise as a direct consequence by the same quantity, or else no more than an alteration in the form of tax-collecting would have taken place. Instead of the present system, whereby the capitalist also advances, as part of the wage, the taxes which the worker has to pay, he [the capitalist] would no longer pay them in this roundabout way, but directly to the state. (‘Moralising Criticism and Critical Morality’ in Marx and Engels’ Collected Works Volume 6)

Another argument that has been put to demonstrate why workers should be interested in taxation is that higher indirect taxes, like VAT and excise duties, will mean higher prices and therefore lower real wages and living standards. However, what this argument ignores is that capitalists will tend to seek the best possible price for their products in the market conditions that are prevailing. Sometimes VAT increases may initially cause some prices to rise as capitalists try to ‘pass on’ the burden of the increase, but capitalists may well find that they have to reduce prices again when sales dip as market forces assert themselves. VAT is not usually charged as a separate tax from the price – prices are usually stated to be “inclusive of VAT” which tends to confirm that sellers sell at the highest price the market can bear.

The other main form of indirect taxes, excise duties, are often levied in those industries where profits are abnormally high because of the existence of monopolies or cartels. It should also be remembered that it is by no means certain that any price rises that do take place (either through tax increases or the continuing process of inflation) will cut working class living standards. In the vast majority of years since the Second World War wages have risen more than prices. Even though the overall tax burden has risen significantly in recent decades, the real purchasing power of the working class has also tended to increase. Most workers are today financially better off than their counterparts 100 years ago who ‘paid’ little or nothing in tax.

That taxation is an issue for the working class is a delusion. Of far more importance for living standards is whether capitalism is in the boom or slump phase of its economic cycle, and on how effective working class organisation in the trade unions is at securing wage rises and better working conditions. The argument between the various political parties about taxation is over which sections of the propertied capitalist class should most bear the burden of the cost of maintaining the functions of the state machine. The burden of taxation cannot fall on the working class, who receive only enough to produce and reproduce their labour power under given historical conditions according to the productive efficiency of society, and as we said in the October 1904 Socialist Standard:

“It thus becomes evident that the taxes must be paid out of the surplus value extracted from the workers by the capitalists; this explains not only the latter’s interest in the question of taxation, but also why it is of small moment to the workers.”

Tinkering with the tax system is of no use to the working class, and it is only another feature of the reformist roundabout. Only the abolition of tax altogether – along with wages, capital, the state and all the other paraphernalia of capitalism, will bring about real social change.

7. Do the Rich Still Get Richer?

Is a classless capitalism on the agenda, as John Major claimed? Does reformist action mean that income inequality is a thing of the past? Or do the rich still get richer on the backs of the rest of the population? Let’s examine whether the rich really are still getting richer out of the unpaid labour of the workers or not. To do this we need to start by examining the nature of wealth in society today.

All the wealth we see around us – the buildings, the roads, the cars, the goods in the shops – has only one source: the application of human labour to materials that originally came from nature. Wealth results from work. All accumulated wealth resulted from work and all the things we use on a current basis came from work. Wealth is of two basic kinds. First, there is wealth that is used for consumption: the food we eat, the clothes we wear, the furniture and household goods we use, the houses we live in, the cars we drive around in and all the other things we consume in the course of living. The second kind of wealth – materials extracted from nature, factories, machines and the energy to power them – is wealth that is used to produce other wealth, or means of production.

Socialists contend that whoever controls access to the means of production controls society. This is why we advocate the common ownership of the means of production as the only basis on which a real democracy and a genuinely classless society can exist. This, of course, is not the situation today. The means of production are not owned in common by us all. Quite the opposite in fact. The ownership of the means of production is concentrated into the hands of a tiny minority of the population. This is as much the case today under capitalism as it was under previous class-divided societies like feudalism in the Middle Ages and slave society in Ancient Rome. It means that capitalism, too, is a class-divided society where a privileged class rules and exploits the labour of those who do the actual work of producing the wealth in society, transporting it and administering it.

Whatever may have been the case at an earlier stage of capitalism, nowadays ownership of the means of production takes the form of a legal right to draw an unearned income from their operation. The most obvious case of such legal titles are stocks and shares.

Since any income is a claim on wealth and since wealth can only be produced by humans working on materials that originally came from nature, all forms of unearned income are ultimately derived from the operation of the means of production and so represent a stake in their ownership even if no direct link can be established with a particular factory, mine, railway or whatever. Interest-bearing bank and building society accounts, and government bonds and National Savings are, like stocks and shares, property rights over the means of production.

So, in modern capitalism, minority ownership of the means of production is not a case of the minority personally possessing as their exclusive private property all land, factories and other workplaces, but of them having a disproportionate share of legal titles conferring the right to draw an unearned, or property, income from the operation of the means of production as a whole.

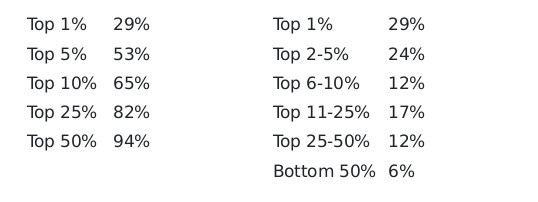

Each year, on the basis of the amount of money people leave in their wills when they die, the Inland Revenue calculates the distribution of property and property rights amongst the adult population. Their calculations are published in the annual Inland Revenue Statistics and also, in an easier-to-follow summarised form, in another official government publication Social Trends. The latest figures available at the time of writing – those for 1992 from the 1995 edition of Social Trends show the distribution of the ownership of ‘marketable wealth’ (personal possessions, cars and houses that are owned for use, in addition to bank accounts, stocks and shares and other financial assets) as being:

| Population % | Marketable wealth % |

| Top 1 | 18 |

| Top 5 | 37 |

| Top 10 | 49 |

| Top 25 | 72 |

| Top 50 | 92 |

Revealing as these figures are – they show that the top 10 per cent of adults own as much wealth as the rest put together – they are not those for the concentration of the ownership of the means of production since ‘marketable wealth’ is precisely what the term suggests; wealth of any kind owned by an individual which they can dispose of for cash. To measure the unequal stake people have in the ownership of the means of production what is relevant is not all wealth but only those forms of wealth that confer the right to obtain unearned income. The ownership of means of consumption like houses, cars and household goods therefore needs to be excluded.

The government itself does not provide figures solely for the ownership of financial assets that bring in an unearned income in the form of profit, interest or dividends and which therefore represent a stake in the ownership of the means of production (though such figures can be calculated from the information the government does provide). The nearest it comes to doing this is the table in Social Trends for ‘marketable wealth less the value of dwellings’. Since houses in fact represent most of the personal wealth that is used for consumption, these figures can be used to get an idea of the distribution of the stake people have in the ownership of the means of production. They show an even higher degree of inequality than for marketable wealth:

We can see that:

- the top 10 per cent concentrate 65 per cent of all financial assets in their hands.

- the top 1 per cent own nearly five times as much as the bottom 50 per cent.

- the top 5 per cent own more than 50 per cent, that is, more than the bottom 95 per cent.

In more homely terms, what the statistics show is that, out of every 20 adults, one has a stake in the ownership of the means of production equal to that of the other 19 of us added together. They confirm that the basis of present-day society is indeed, as socialists contend, the concentration of the ownership of productive resources in the hands of a tiny minority of the population.

Unlike reformists such as those in the Labour Party – who once stated that they wanted to squeeze the rich ‘until the pips squeaked’ – socialists do not advocate as the answer to this state of affairs a redistribution of wealth from the rich to the non-rich. That would be futile since, even if it could be achieved, it would only be undone again by the workings of the capitalist system, which has an in-built tendency for the rich to grow richer.

The ownership of capital confers the right to appropriate a part of the new wealth that is being produced every day. Most of this new wealth – around 80 per cent in fact – is used as means of consumption by workers from their wages and salaries, by capitalists from their rent, interest and dividends, and by the state from the taxes it levies. The rest, under the spur of competition between capitalist firms to maximise profits, is accumulated as means of production, as further capital invested to yield an unearned income for its owners.

This accumulation of capital out of profits produced by those who operate the means of production is what capitalism is all about. Capitalism is an economic system under which means of production are accumulated in the form of profit-yielding capital. In concrete terms, what this means is that the stock both of the physical means of production (factories, plant, machinery, materials, etc.) and of its monetary form, capital, grows over time. This is by no means a steady process – it is halted and even reversed from time to time during wars (when wealth is physically destroyed) and in slumps (when the same thing happens and when the value of the surviving capital falls) – but the long-term trend is upward. This must mean that in the long run those who own the means of production – the rich – get to own more means of production, more capital, and therefore get richer.

Reformist defenders of capitalism sometimes try to deny this and point to the fact that, whereas up until the Second World War the top one per cent owned nearly 60 per cent of personal wealth and the top ten per cent owned nearly 90 per cent, the percentage shares are considerably less today. This is true, but to say that the relative shares of the top groups have fallen is not at all the same as saying that the absolute amount of wealth they own has decreased. In broad terms what has happened since about 1920 is that the rich – the top 1-5 per cent – have still grown richer but at a slower rate than some other sections of the population, notably those in the 5-70 per cent range.

This has reduced the rich’s share of total wealth but not the amount of wealth they have gone on accumulating. The rich still exist. They still grow richer. And they still enjoy a privileged lifestyle out of the ever-increasing proceeds of the exploitation of the labour of the non-rich. This is an observable economic tendency of capitalist development, and one that the reformists have not been, and will not be, able to change.

Socialists contend that the economic cycle of booms, crises and slumps is endemic to the capitalist system of production. During the nineteenth century it was Karl Marx who pointed out that capitalism inevitably develops unsteadily with periods of both expansion and contraction, and socialists claim that his analysis is essentially still valid today, in his principal work “Capital” Marx formulated the basic law of capitalist progression in the following terms, commenting that:

“The factory system’s tremendous capacity for expanding with sudden immense leaps, and its dependence on the world market, necessarily give rise to the following cycle: feverish production, a consequent glut on the market, then a contraction of the market, which causes production to be crippled. The life of industry becomes a series of periods of moderate activity, prosperity, over-production, crisis and stagnation.” (Volume One, Chapter 15)

Since Marx wrote these words many have sought to refute them. In Marx’s day and for some decades afterwards, capitalist economists claimed that crises and slumps were not integral to capitalism at all, but that they were a phenomenon brought about by outside interference in the normal workings of the free market. They claimed to identify market irregularities promoted by excessive trade union power, restrictions on free trade or incorrect government monetary policy as the cause of economic slumps. Just as the followers of Margaret Thatcher did later, these economists believed that if the free market was left to its own devices, there would be no slumps at all. Their view was based on an acceptance of the doctrine propounded by the early nineteenth century French economist J.B.Say that “every seller brings a buyer to market”, with supply creating its own demand. They argued that the price mechanism is the most efficient allocator of resources and that unemployment and economic stagnation could be avoided if the “invisible hand” of the market was left to weave its magic.

Beside some of the free market zealots in the Conservative Party, few today believe this. Most now accept that events have proved the free market to be just as incapable of providing lasting economic growth as restrictive state intervention. Relatively few, however, understand why. Marx was among the first who were able to identify the faulty reasoning that lay behind the case of the free marketeers:

“Nothing could be more foolish than the dogma that because every sale is a purchase, and every purchase a sale, the circulation of commodities necessarily implies an equilibrium between sales and purchases…its real intention is to show that every seller brings his own buyer to market with him ……but no one directly needs to purchase because they have just sold.” (Capital, Volume One, Chapter Three)

According to Marx, the division in capitalism between the buyers and sellers of commodities raises the possibility of economic crisis and slump, as holders of money do not always find it in their interests to immediately turn money into commodities. Therefore, so long as buying and selling, money, markets and prices exist, so will the trade cycle.

By the time of the Great Depression of the 1930’s, most economists had come to agree that slumps were integral to capitalism, having followed the lead in their time provided by John Maynard Keynes. Like Marx before him, Keynes argued that Say’s Law was nonsense and that the free market did not naturally lead to an equilibrium point of full employment with sustained growth and that capitalism, if left to its own devices, would stagnate, just as it had after the Wall Street Crash of October 1929. Keynes and his followers took the view that as capitalism developed, the observable tendency of the system to concentrate wealth into ever fewer hands would lead to excessive saving, hoarding of wealth and a decline in overall demand. This in turn would plunge capitalism into prolonged slump.