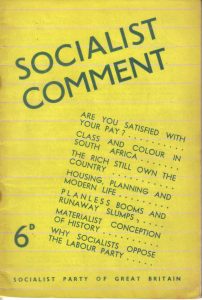

This pamphlet consists of a selection of articles that appeared in the Socialist Standard during 1955 and 1956. They have been published because they deal with issues of current interest and give the Socialist Party’s attitude to them in a handy form.

This pamphlet consists of a selection of articles that appeared in the Socialist Standard during 1955 and 1956. They have been published because they deal with issues of current interest and give the Socialist Party’s attitude to them in a handy form.

CONTENTS

1. The Rich Still Own the Country

2. Are You Satisfied with Your Pay?

3. Planless Booms and Runaway Slumps

4. Housing, Planning and Modern Life

5. Class and Colour in South Africa

6. Why Socialists Oppose the Labour Party

7. The Materialist Conception of History

THE RICH STILL OWN THE COUNTRY

LABOUR SPOKESMEN ADMIT OUR CHARGE

Though the Fabian forerunners of the Labour Party recognised well over half a century ago that the basic fact about capitalism Is that the means of production and distribution are owned by the small capitalist minority, the four Labour Governments of 1924, 1929, 1945 and 1950, did nothing about it. The early Labour Party placed on record that 10 per cent. of the population own 90 per cent. of the wealth and promised to change this situation: it was to be their alternative to the establishment of Socialism, their answer to the S.P.G.B. For a time, in the burst of Labour enthusiasm after the second world war, some of their spokesmen claimed that the aim had been practically achieved. They said that the Welfare State and the Labour policy of “Fair Shares for All” had pretty nearly abolished the old extremes of riches and poverty. We said that there was absolutely no truth in this, and two Labour Party supporters have since admitted that we were right, The occasion for this belated confession is that their defeat at the 1955 General Election set the Labour Party the task of finding a new programme to get them back into power, and the line they are preparing to take is a campaign for “equality of ownership.”

Writing in the Sunday Pictorial (27/11/55) a Labour M.P., Mr. Wilfred Fienburgh, said:-

“Let us face it. There ARE two classes in Britain to-day. There is the one-tenth that owns nine-tenths of the wealth and there are the others, 45,000,000 others, who own practically no wealth at all.”

And Professor W. Arthur Lewis, who wrote on “The Distribution of Property” in the Labour journal, Socialist Commentary (December, 1955), where he said: –

“Two-thirds of the private property in this country is owned by less than 4 per cent. of the population. This uneven distribution lies at the root of most of the evils with which Socialists have been concerned in the economic sphere – especially the uneven distribution of income and of economic power.”

Professor Lewis went on to say that his Party has not yet even discovered how to tackle the job.

“One of the principal tasks of a Socialist Party is to alter the distribution of property, and we have not yet begun to use any tool which can have this effect.” (His Italics.)

Here, of course, the S.P.G.B. takes issue with the Professor. It is not one of the tasks of a Socialist Party to alter the distribution of property within the capitalist system, which is what he still aims to do. The aim of a Socialist Party, though not of the Labour Party, is to end private ownership – transform the means of production and distribution into the common property of the community.

Professor Lewis says that the Labour Party thought that nationalisation and death duties would make capitalist property ownership more equal. He has no difficulty in showing that they haven’t had this effect. The S.P.G.B. was saying this before the Professor was born, but though he has, at this late stage, recognised the truth of what we said, he blunders on into supposed other ways of abolishing the basis of capitalism without abolishing capitalism. His new suggestions are just as fatuous as those he rejects.

We can, first, briefly establish our point that he is not even considering the establishment of Socialism, for although he starts by identifying himself with Socialism, he goes on to line himself up with “believers in a mixed economy” and, indeed, he concedes that his objective of “the more even distribution of private property” is one he shares “with all liberals.”

He first toys with the idea of using the proceeds of death duties to make grants to those who own no property so that they can buy houses, but finds a snag in it because, he says, the thriftless ones will merely spend the money on other things or let the house fall into disrepair. It does not occur to the Professor – who, by the way, is regarded by the Manchester Guardian (2/12/55) as a potential saviour of the moribund Labour Party – that what the propertyless live on is their wages and. as has been shown in practice time and time again, subsidies on housing or on other necessary items of expenditure operate to discourage wage claims, leaving the workers where they were. Indeed, the Professor manages to write a lengthy article on the condition of the propertyless majority without even mentioning the fact that they are a wage-earning class, dependent for their standard of living on what they can get for the sale of their working energies to the employing class.

This fact which he completely ignores makes nonsense of his other schemes for rendering the ownership of property less unequal. What he proposes is that the Government shall acquire property by a capital levy or by making a profit on its nationalised industries or by levying an additional tax on company profits, to be taken out by the Government in the form of owning company shares.

How this would benefit the propertyless working class Professor Lewis does not explain; which is not unnatural because the net effect would be nothing at all. The Government would either use this additional income to reduce taxation in other directions, which would leave things as they are, or would acquire more nationalised industries, which also would leave the propertyless still propertyless. It may be that Professor Lewis is silly enough to suppose that the Government as employer would give higher wages – something contrary to all experience – but in any event he does not offer this suggestion.

Finally, if it were possible (which it is not) to make the working class into small property owners, this would simply make capitalism unworkable. With their hands thus strengthened in the wages struggle the workers would be able to press up wages to the point of destroying the employers’ profits, the result of which would be widespread bankruptcy and unemployment. Even the less powerful effect of “full employment” has shown how this would operate, for it has been met by Labour and Tory Governments alike with the policy of “wage restraint,” and latterly by the pleas of economists and others for more unemployment in order to keep industry working profitably by depressing wages.

Professor Lewis’s “brilliant” notions are just a variation of the original Labour Party schemes and will solve no working class problem. He is another example of the truth that the Labour Party will try to do everything with capitalism except to abolish it and establish socialism.

ARE YOU SATISFIED WITH YOUR PAY?

Ask any body of workers if they think they are getting enough pay, the pay they think they are worth, and it is safe to say that nine out of every ten would answer No! They nearly all think they ought to get more, and would get more if things were run properly. They nearly all have a vague feeling that things aren’t run properly. They are annoyed that nobody – this includes the trade unions, the employers, the political parties and the Government – does anything about it, and they all have some notion about what ought to be done. Some point to the impossibility of keeping themselves and their families “decently” in face of the cost of living – in their view it ought to be the duty of the employers or the Government to see that everybody has enough to maintain this “decent” standard of living.

Some think that things would be all right if wages were raised and their employers’ profits lowered. But if they happen to work in a firm or an industry where sales are falling and profits are small or non-existent they look to the Government to give subsidies or do something to improve the sales of the article they produce. Lots of workers blame or envy other workers. The labourers envy the craftsmen, while the craftsmen and foremen complain that they do not receive wages sufficiently above the labourer’s rate to compensate for their skill and responsibility.

Many teachers have a special resentment because, so they allege, they receive no more than do dustmen. University graduates think that a proper wages policy would recognise the importance of having a degree, and scientific workers think that the scales are unjustly weighted in favour of administrative workers. Feminists clamour for the male “rate for the job” and provoke some of their male colleagues into demanding “justice” for the married man with dependants. The queue of the disgruntled stretches indefinitely and encircles the globe.

They are all there, the bank clerks and postal clerks, the lawyers, the doctors, the dentists and nurses. The shopkeepers, too, have their grievances against the manufacturers. Then there are the pensioners, the police, the soldiers, the prison warders and the parsons. At the end of the line are the non-workers, the small unhappy band of surtax payers and millionaires, who swear that high taxation compels them, if they are to live the lives of conspicuous wastefulness fitting to their station, to overspend their incomes and eat up their capital; a practice as loathsome to a capitalist as is cannibalism to a missionary.

And for every group of complainants there is an aspiring trade union official, politician, or economist with a glib solution: The solutions are too numerous to list here. They are seemingly as varied as the occupational groups from which they spring, but they all have one thing in common. They all assume that there is, or could be, in the world of capitalism a defensible social principle by which wages could be fixed at a “proper” level. They all ignore the facts of capitalist life. As practical solutions they are all useless.

The Law of the Jungle

Capitalism knows no social principle of distribution according to need, or responsibility, or skill, or training, or risk, or so-called “value of work,” or “usefulness to the community.” If capitalism has anything that approaches a principle it is that income shall be in inverse proportion to work. If you own capital in sufficient amount you never need work at all and the more you avoid work in order to enjoy luxurious living the greater the esteem and attention you will have bestowed upon you.

The Socialist knows why this is and how the system works. Society’s means of living are owned by the propertied class, the capitalists who are in business to provide themselves with their kind of income, profits. They employ the working class in order to make profit out of them, a proceeding the working-class are forced to accept because they are propertyless. The capitalist pays as little as he can for the kind of worker he needs. All the worker can do is to bargain and struggle to get as much out of the employer as circumstances permit, which depends on whether the capitalist needs the kind of skill the worker has to offer. If the employer needs a certain kind of skill and if the number of workers having that skill is limited the employer will have to pay accordingly for it, he will have to pay more to the skilled than to the unskilled worker. But if owing to the decline of a given trade, or the invention of a machine which replaces craftsmanship, skilled operatives are not in demand, their wages will fall.

In the depression of the nineteen thirties apprenticed engineering craftsmen, skilled coal miners, university graduates, and agricultural labourers, were a drug on the market. Capitalism had no need for all there were of them and their wages fell. During the war capitalism had need of coal and food, of engineering and chemical products, and members of all these groups had their chance to push up wages beyond the rise of the cost of living. “Merit” and “human needs” “and” usefulness to the community” and all the other fine-sounding phrases, have nothing to do with it.

What counts is whether the worker is useful to the capitalist, and the only usefulness the capitalist knows is usefulness in making profit. The only argument he has to listen to is the fact of inability to get sufficient of the workers he needs, and the amount of strike pressure trade union organisation can bring to bear to prevent him getting enough workers at the wage he offers.

Is it crude, callous and inhuman? Of course it is. It is the law of the jungle, the only law capitalism knows.

And has Socialism any alternative to offer? Indeed it has, but by Socialism we mean the Socialism of Socialists, not the spurious State capitalist nostrums offered by the Attlees and Bevans and the clique who run capitalism in Russia.

All over the world the cut-throat capitalist wages system operates and only Socialists have as their aim the replacement of capitalism by a socialist system of society in which there will be no wages system, no propertied class and working class, the one living on income from property and the other on wages. When we have Socialism people will work co-operatively to produce what all need and all will freely take what they need out of the products and services cooperative effort achieves.

Of course, the pseudo-Socialists named above all pay lip-service to the ideal of abolishing capitalism and the wages system, but whether or not they understand what they are talking about they show by their actions and programmes that they do not intend to seek that solution. They all in their time bleat about the need for bold, far-reaching action, but all with one accord recoil from the Socialist objective they profess to desire.

For the working class of the world the choice is simple, either to take the organised political action necessary to introduce Socialism or to continue with capitalism. The one thing that cannot be had is to impose on the capitalist jungle some socially acceptable and satisfying wages policy.

PLANLESS BOOMS AND RUNAWAY SLUMPS

Although the periodical crises under post-war Labour Government rather took the shine off the idea of planning, there is still a lot of belief in it. A hundred years ago those who believed that capitalism is the best of all possible systems had a different idea. They thought that if each individual went about the business of making money or getting a job on his own the medley of efforts and strivings would, like a mosaic, combine together to make harmony for the nation as a whole. It did not work like that, and 19th century capitalism was rent by class struggle and rocked from time to time in the cycle of boom-crisis-slump.

So the theory grew up, not only in Labour Party circles, that the remedy must lie in the direction of planning. The same idea caught on in other parts of the world, and many people believe that governments, alone or in international organisations, can and do plan and control the course of economic events. That is why the “inflation” crisis of 1956 and the dark forebodings of another slump inspired such bewildered comments from the “experts” and the newspapers. For if everything is planned and under control then the crisis and possible slump must have been planned – which is absurd – or must be due to pure ignorance and incompetence by the Government and its advisers. Certainly the Government’s defenders have much to explain away.

To start with, the theory that everything is planned to run smoothly according to design, requires, not only that there shall be no crisis, and no slump to come after it, but also that there shall be no bursting boom to come before it. So the boom itself proved the failure of planning, though Government spokesmen were claiming it as their own work and soliciting votes on the strength of it at the 1955 General Election.

The next thing is the “inflation” from which they say we are all in dire peril. They are all now agreed. Government and Opposition alike, that “inflation” is the enemy, as a start, in February 1955, the Government raised the bank-rate from 3½ per cent. to 4½ per cent. This was the first step to halt that enemy, and it was followed in July by the instruction to the banks to restrict loans. These measures were supposed to be the cure. They failed, and in October came the emergency budget with more measures. Why then the need for more and still more remedies to curb demand and capital investment. The answer is in the admission in a Daily Mail editorial of 17th February, 1956, that “inflation . . . gains momentum every day,” and in the declaration of Sir Eric Gore-Brown, chairman of Alexanders Discount Company (a declaration endorsed by the financial editor .of the Manchester Guardian 17/2/56), that “in his view monetary restraints, for example the use of the bank-rate and a credit squeeze, could not either alone or in combination, stop the spiral of wages and prices.”

The leader-writer of the Daily Mail (17/2/56) seeks to condone the failure of the Government to control this crisis with the plea that “in some ways the looming crisis is one we have not encountered before.”

This crisis, according to him, is different because unlike earlier ones, it “could be called a crisis of prosperity, for it is caused by the weight of earned money making undue demands on our resources.”

Far from being novel this has always been a mark of booms and crises. Every boom has the superficial appearance of “too much money chasing too few goods,” as every depression has the superficial appearance of “too many goods chased by too little money.”

But booms and slumps are not caused by monetary factors, but by conditions in the field of production and marketing, basically by the class ownership of the means of production and of production for sale and profit.

When the capitalists are convinced that they can look forward to a period of expanding sales and rising profits they rush in to enlarge their factories, buy more machinery and raw materials, and bid for more workers. They all use what money they have and try to borrow more. In these conditions prices and wages rise and the competition for loans sends up interest rates. The raising of the bank-rate in 1955 only put the seal on a rise of interest rates that was already happening.

Anyone who thinks this has not happened before needs only to look at the situation in 1920.

There was then a seemingly unlimited demand for goods and for workers. The trade unions (mainly of skilled workers) that kept an unemployment register showed unemployment of about 1 per cent. The cost of living was rising, it jumped by 23 per cent. in the year ended November 1920. Bankers and others were complaining of “inflation” and the Cunliffe Committee had reported at the end of 1919 on measures to combat it.

And the bank rate was in the news as it was again in 1956. In February 1956 it was raised from 4½ per cent. to 5½ per cent. In November 1919 it was raised from 5 per cent. to 6 per cent, and in April 1920 to 7 per cent. Then, as now, one of its declared aims was to discourage lending by the banks. Mr. A. W. Kirkcaldy in his British Finance (1921. p. 55) says of the first of those two rises: – “in the main it was designed to check the speculative movement that became pronounced during the closing months of 1919, and to administer an effective check to the demand for further expansion of bank credit, if not to commence a gradual process of deflation.”

Inflation the Friend – or the Enemy?

In 1920 and 1956, inflation is, by common consent, the enemy. It has not a friend in the world, or at least not one who will disclose his friendship openly. It was not ever thus. In 1932 Lord Beaverbrook’s newspapers were running a great campaign for inflation! The Sunday Express (15/5/1932) had this:-

“The movement is growing and spreading. Most public men are now in favour of inflation. Practically every Member of Parliament speaking in the debates is an inflationist. Some of them are no longer even shy of the word. The movement is extended to many of the newspapers. It is even being adopted by the Times.”

Prominent members of the Labour Party were rushing in to support the great new cause of inflation.

Now they have got what they asked for they like it hardly more than they did the slump situation of 1932 from which inflation was to save them.

Many of them are fearful that this “inflation” crisis might be followed by a slump. (The 7 per cent. bank rate of 1920 preceded the over 2.000,000 unemployed of 1921).

So indeed it may. There are certainly in evidence some of the chaotic features that precede slumps and that in any event provide proof of how planless capitalism always is and must be.

The American and other governments are embarrassed by the enormous stocks of unsaleable wheat and butter they hold. Was this planned? And the motor manufacturers here and in the U.S.A. are cutting back production “temporarily” because of stocks of unsold cars. But simultaneously all the big motor companies are going ahead with plans to expand their manufacturing capacity, amounting in the aggregate to many tens of millions of pounds. This is not planning but gambling. They all hoped that demand would increase again and absorb their still further expanded production. They all feared that there is a possibility that demand may collapse instead of increasing, but they could not be sure, and no big company dare drop out of the race to design and produce new and better cars and more of them. The company that ceases to compete fades out. And as if the car manufacturers of the Western Powers had not enough to worry about. Russia, too, was now an exporter.

But who knows how capitalism will run in the next five years or even one year? It may happen soon that the world’s markets will collapse as in 1921 and 1930 – or it may not; or it may happen that particular countries, among them Britain, and particular industries may be hard hit while the rest may be little affected. Such things have happened before and could happen again. The evidence does not by any means all point to a serious depression. A large and rapidly growing place in production is being taken by the new atomic and electronic industries. For production and for military purposes enormous new investments are going on, and will go on even if depression does hit some established industries. A case in point is the raising of £24 million new capital by Associated Electrical Industries, Ltd., only one of the many firms interested in this new and rapidly expanding field. It will, of course, seem to the men inside each of firms such as A.E.I., as to the men inside the motor firms, that they are carefully planning every move they make and with every possible effort to foresee the conditions in which their products will be coming on to the market one year or many years ahead. But this is all beside the point as far as world demand and world supply are concerned. While every British firm is planning to sell its products in the world market, so are similar firms and governments in every other country. They do not know very much about the eventual size of the potential world demand for all their products, and they know less still about the total supply there will be to satisfy the demand when all these unrelated plans for expanded production are completed and the bigger flow of products pours out. They all hope to get a large enough share of the market, and all hope that the price they get will be a profitable one. They all hope but they cannot know. They all gamble on the future. And every now and then the gamble produces chaotic conditions of such extent as to disorganise all markets and slow down all production. Capitalism is that sort of system, and there is no cure except Socialism.

HOUSING, PLANNING AND MODERN LIFE

“I was struck with the magnificence of the building . . . ‘One should think,’ said I, ‘that the proprietor of all this must be happy.’ ‘Nay, Sir,’ said Johnson, ‘all this excludes but one evil – poverty.’” –Boswell’s Life of Johnson.

People marrying today have no better prospect of somewhere to live than they had in 1945. That is not an uninformed guess: it is a statement made on the third of July 1955 in the Sunday Pictorial. How much attention it gained, among the nymphs and the strip cartoons, is uncertain. It should have had a great deal – most of all from those who believe that capitalism can solve its problems.

Between the wars, four million houses were built in Great Britain, and by 1939 there were twelve millions altogether. With the slum clearance programmes two-thirds completed, about a quarter of a million remained condemned as unfit for habitation, and nearly half a million were “overcrowded.” Another half-million were destroyed or severely damaged during the war – most in docklands – and crowded industrial areas, and so anticipating further “slum clearance.” In 1945 authorities agreed that four million new houses were needed in the next ten years; in fact, at the end of that period two millions had been built.

Even allowing that it is only half the estimate, two millions is an impressive number. Indeed, nobody wants figures to know that a great deal of building has been done. Small, semi-rural towns have dilated to populous urban areas; on the outskirts of cities, the council estates (and latterly “private” ones, too) have mushroomed; in the cities themselves, clumps of prefabs and great chest-of-drawers blocks of flats have risen on bomb-sites, waste patches, football fields – every place, in fact, where there was land to spare for the housing of working people.

The solution of the housing problem has been the great promise of the post-war years; getting a council house, once slightly shameful (“corned beef islands,” the estates were called), has become heart’s desire to millions. Local authorities, faced with endless lists of applicants, made dire need almost their sole criterion. Most have used the “points” system to ensure that the houses went to the largest families with the worst accommodation; a temporary relief which ensures more overcrowding in a few years on the council estates. Outside of what is provided by the councils, the letting of houses has entirely disappeared. Virtually all that is available to childless or one-child couples is furnished accommodation at extortionate prices, or house purchase.

For most people, buying a house is out of the question. Usually a tenth of the price is to be paid as deposit; add on legal charges and other expenses, and an initial outlay of £300 is needed for a very modest house. Recently it has become possible to obtain 95 per cent, and even 100 per cent mortgages: that sends up the weekly repayments to something like £4 – again, out of the question for most people. More are buying houses, because it is the only solution to their housing problem; over 90 per cent. of them – according to figures recently published by the Association of Building Societies – houses costing £2.000 or less. In short, some working people can buy houses, but only cheap ones.

What is obvious is that all today’s housing schemes rest entirely on the assumption of full employment. Buying a house takes 15 or 20 years, and if you do it for less than £3 a week you’re lucky. Council tenancies cost approximately double those of the older houses with controlled rents. In the last few years there has been a great deal of talk about “improved standards of living” that has been based largely on working people buying their own houses and being fixed up in smart little boxes with all-electric kitchens. The truth is that most people, with jobs and plenty of overtime, struggle for financial survival after having their housing problem solved. The Daily Herald, on the 16th of September. 1955, gave some sobering facts about the lucky ones who are supposed to exemplify the better standard of living:

“In a London court last week an eviction order was granted against a £l5-a-week factory worker for non-payment of rent. He has been living in a 32s.-a-week council house, with three children, a host of debts, and a TV set.

The man who sought and won the eviction order against him on behalf of the local council had no sense of elation about the success of his mission.

He, too, is living above his means . . . He can’t afford to smoke or drink. He hasn’t a suit to his name – and wears sports clothes for economy reasons. He has already borrowed £245 against his life insurance – and he now faces a summons for non-payment of £5 rates.”

The housing problem, in fact, is not post-war at all: it is the continuation of one of capitalism’s oldest problems. The working class never has been adequately housed. Before the war it was the slum problem – rehousing people who lived in such squalor that their children were malformed and tuberculous. Plenty still live in those conditions, by the way, and are not rehoused because they can’t afford to be. However, the dominant factor in the housing problem since the war has been that most people are in work and so are asking for houses to themselves.

In a London suburb there is a row of houses, built just before the war, which still bears a signboard announcing in faded letters that £20 down will buy one. Passers-by lament the change without realizing what it was. Now they haven’t houses; then, they hadn’t the money. As soon as there is legislation which allows rents to be raised (and that seems a near-future inevitability) the post-war housing problem will fall back into its century- old perspective of people needing houses but unable to seek them.

For – and this is the great fact about the housing problem – houses are not produced to satisfy needs. Nor is anything else in this world. Food is not produced to be eaten, clothes to be worn, or anything else for its utilitarian purpose. All things, under capitalism, are produced with one motive only: sale and profit. Thus, at times when millions have needed it, food has been destroyed; thus, at any time (including today) anybody can have what he can pay for and nothing else. Note, please, that rich people have no housing problem. The Observer and the Sunday Times advertise houses to satisfy anyone at £4,000 and upward. How is it, though, that two million new houses in ten years leave the demand still unappeased?

There are all sorts of contributory immediate answers – people keep on marrying, millions have shared houses for years, and so on. They all boil down to the fact that working-class families are in unsuitable accommodation and want to get out of it: the more important fact is that it always was unsuitable. Houses built for working people are small, cheap houses – soon overcrowded and soon dilapidated. The labourers’ dwellings and tenements and industrial estates of the last century are the slums of this. Many thousands of people, incidentally, will still live in houses which were flung up over a 100 years ago to cram workers into the industrial towns. Go through the Lancashire mill-towns, and you see rows of grimy little dwellings with dates -1833, 1834,and so on – on their fronts and earth-closets at their backs. Go through London’s suburbs, and you see the unlovely prefabs of 1945; many of them are having their lives formally extended for several years because their inhabitants cannot be rehoused elsewhere. So there is a perpetual process like that of the Augean stables, where the troublesome matter flows in at exactly the same rate as it is cleared out.

The biggest post-war housing project of all has been the building of “new towns.” Really vast estates attached to smallish country towns, they are the planners’ pride. It is worth examining them to see how much they really contribute to better living standards and human happiness.

Essentially, they represent the way of life provided for the modern industrial worker; the north country towns do the same for older, heavier industries, and the outer suburbs of southern cities the different amenities of the petrol-engine and electric-motor era. In them is incorporated, actually and potentially, the culture of the mid-twentieth century. A new town has no music-halls, no street traders or little gold-mines. It is laid out in careful uniformity, and all the inhabitants keep their front gardens tidy because they are told they must.

The buildings are grouped neatly according to function or income; shops together, civic buildings together, rows of houses with garages for the higher-income groups. Much has been made of this last point; in new towns, they say, the officials and professional people and managers live close to the rest. The fact may be true, but its implication is nonsense. There is as much snobbery in the new towns as anywhere else, and placing people close together makes no difference to it. In every big city in the world, wealth and poverty are contiguous with a world between them. There are plenty of places where one side or one end of a street regards the other as “a different class.”

The workers in the new towns are dependent on local industries, which are mostly of the newer sorts – plastics, electronics and so on. With largish families (the chief condition for getting the houses) and high rents, they can hardly lead lavish lives. Consequently, there are not many pubs or cinemas, and the new towns-like the estates – form “community associations” which really are means of recreation for people who have not much money and must look after young children in the evenings. Local transport generally is poor, and the distances to former neighbourhoods considerable: the new towns impose fixed ways of living as firmly as the old.

Are those better, more satisfying ways? Consider the man living in Harlow or Stevenage or one of the others. He is fairly young and fairly skilled and has a family. He works in a radio or plastics factory; he works as many hours as he can to make ends meet, and if the factory closes half the town will be unemployed. He has a television set and complains of the programmes, His wife uses Omo and Daz so that her family’s clothes are white and they all use green toothpaste to keep their breath sweet. They haven’t a book in the house, but they take in Reveille, Tit-bits, Woman and the Daily Mirror. They are scared of having more children, getting diseases, and Henry’s firm becoming slack, and they do the football pools in the hope of buying themselves out of it all.

The condition of the working class, in new towns and old towns remains a deplorable one of insecurity and want. If material improvements can be discerned {which is debatable) they are outweighed by frustrations and fears of which our grandfathers knew nothing. Indeed, the degree scarcely matters; if things became much better they would still be bad. Housing is one of the innumerable problems which capitalism has created and cannot solve, simply because capitalism has no care for human needs. Many people refuse to believe that such problems cannot be solved within the capitalist system: the astonishing thing is that they are refusing to believe their own eyes.

Can Socialism house people, as people should be housed? The short and simple answer is that there will be no money barrier to the satisfaction of any need when all the means of production are owned by every person. The cheap and shoddy in houses, as in everything else, will vanish when there is no profit motive. As for the question of space – well, think of all the buildings which nobody will want. Shops, banks, exchanges, offices of every description … and, in addition, a lot (an awful lot) of buildings which only a perverse society could think suitable for human beings.

NOTE: The figures about rents and house prices apply to southern England. In the north and in Scotland they are rather lower. So are wages.

CLASS AND COLOUR IN SOUTH AFRICA

Class struggle

The class struggle in a fully-developed capitalist society is a struggle between the ruling class, which owns the means of production, and the working class, which operates the means of production and is exploited by the ruling class. Such a struggle can be observed in full swing in countries like Britain and America. But in societies which are slightly less fully developed the capitalist class has to fight not only against the working class, but against the previous ruling class – that is, the class which derived its power from the ownership of land, and which formed the master class before the progress of large-scale industry threw up another class to challenge it.

Nineteenth-century Britain witnessed the strife between the old landed upper class and the rising industrial upper class, culminating in the victory of the latter in the passing of the Reform Bill – in 1832 and the Repeal of the Corn Laws fourteen years later.

The situation in South Africa at the present time is in some ways not dissimilar to the situation in this country a hundred and thirty years ago. There is a class which draws its wealth from the ownership of land; and there is a class which draws its wealth from the ownership of industry. There are, in fact, two kinds of society in South Africa: the old agricultural society, and the new industrial society. South African politics reflect the economic and. social struggle between the old form of society and the new.

Dutch South Africa

The farming community of South Africa is very largely composed of Afrikaners – descendants of Dutch, Flemish, German Protestant and French Huguenot immigrants. These Afrikaner farmers own the land and employ Negro labourers. The landowners are and always have been determined that the Bantu shall form merely a floating population, with no stake in the land. The Bantu farm-workers have very little money; the white farmer pays the greater part of his labourers’ meagre wages in kind, in the form of huts to sleep and eat in, rough grazing for their few head of cattle, and seed for their garden plots. This form of society has existed and from the point of view of the ruling and owning class has prospered almost since the first settlers were put ashore by the Dutch in the 17th century to hold the Cape as a valuable halfway house for the ships trading to the East.

British South Africa

The Dutch took possession of the Cape as a landfall on the way to India; and the British stole (or, to use a more polite word, captured) it from them in 1806 for the same reason. As the century wore on, and the Dutch quarrelled with their new masters, the more independent spirits among the settlers trekked north, to Natal, then across the Orange River, and finally across the Vaal River. But British settlers followed them, attracted by the lure of diamonds and of gold.

The apostle of this industrial expansion was Cecil Rhodes at once Prime Minister of the Cape and Managing Director of the British South Africa Company; its centres of operation were Kimberley and the Witwatersrand, and its outlets Cape Town and the ports of Natal. A number of armed clashes between the British and the Boers culminated at the turn of the century in the Boer War, which, at length, the British won, by means of destroying the farmsteads of their enemies and transporting their families into concentration camps where many of the Boer children died. It may be doubted whether at that time the strength of the new capitalist class was sufficient by itself to overcome the class which drew its strength from the land; but the ultimate issue was put beyond dispute by outside intervention. The farming-landowning class had been cut off from its former fatherlands in Europe; while the capitalist class could count on the help of imperialist Britain, then the greatest industrial power in the world.

This is the background of the South African scene. But the Boer War did not settle the matter. There was, and still is much vitality left in the Afrikaner farming class. It still carries on its resistance to the industrial capitalist class; but in the long run one of them must go down before the other.

Black South Africa

The hostility between these two classes can be seen clearly in their respective attitudes to that majority of the South African population – the Negroes – who form the bulk of the working-class alike on the farm owned by the Afrikaner and in the mine or factory owned by the Britisher.

Each of them regards this class as subordinate. But while the Afrikaner’s self-interest drives him to adopt a harsh and oppressive policy, the Britisher, also motivated by self-interest, tends to take a more “liberal” point of view.

To the Afrikaner the Negro has two possible capacities. He is, first and foremost, a rival for the ownership of the land. There were in 1946 over 8,000,000 Negroes in the Union, against 2,300,000 whites, nearly 1,000,000 Cape Coloured (of mixed white and black ancestry) and 200,000 Asiatics (nearly all of them Indians). Most of the Negroes are descendants of the Zulu-

Xhosa peoples, who came into the country from the North, while the whites came in from overseas – the whites having exterminated or driven out the original black inhabitants of the area. These white and black invaders naturally found themselves in competition for the possession of the land. It has always been the policy of the Afrikaner landed interest to confine Negro ownership of land to certain fixed “Native” reserves; the Bantu can emerge from these reserves only as landless labourers on the white-owned farms, and must never be allowed to take root in the great areas of South Africa which are kept exclusively for white ownership. This restriction of Negro ownership always applied in the Afrikaner territories of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State; and the granting of Dominion status to South Africa in 1909 by Asquith’s Liberal Government enabled the Afrikaners (who were the numerical majority of the white population) to impose the same rule throughout South Africa. Since 1913 Negroes have been able to own land only in certain carefully limited areas of the Union. At the present time more than three-quarters of the total population of South Africa can own land in only one-tenth of its territory. This fragment of South Africa set aside for Negro ownership consists largely of less favoured land in remote districts, such as the Transkei Reserve in eastern Cape Province. At the beginning of 1955 there was only one important urban area throughout South Africa where Negroes could own land; and that was in a suburb of Johannesburg called Sophiatown.

The Nationalist Government has now put a stop to this anomalous situation. It built a new settlement of corrugated-iron-roofed one-storey-huts at Meadowlands, eleven miles outside Johannesburg; and forcibly evicted the Africans of Sophiatown from their freeholds and carried them and their goods to Meadowlands. There the Negroes are allowed to become tenants of the land; but are not allowed to own it. The Africans had no say in the matter. The Government said they must go, fixed the exact days, and provided transport and police. This operation was carried out under the Native Resettlement Act, passed by a Parliament elected almost exclusively by the whites. The Nationalists claim that the removal to Meadowlands was aimed solely at improving Native housing; but there are other African locations around Johannesburg where the housing conditions are worse than at Sophiatown; and, what is more, the shacks of Sophiatown were destroyed and the area reserved for white occupation – this in a city which is short of 50,000 houses for its black population (Daily Telegraph. 1-0/2/55). The real aim was clearly to destroy the African’s ability to own land in one of the few urban areas where he still had that right.

Apartheid

The Afrikaner, then, sees the Negro as a competitor for the ownership of the land; and is led thereby to support apartheid, the policy of confining each of the groups in South Africa to its own areas – with the unspoken corollary that the areas reserved for the white minority shall be much larger than the areas reserved for the coloured majority. But to the Afrikaner the Bantu is not only a competitor for the land; he is also a farm-labourer. If apartheid were carried out in full, as is advocated by the extreme wing of the Nationalists, who would do the work? The extremists, those who embrace apartheid in all its pristine purity, say that the Boers must return to the ways of their ancestors, and themselves work their farms with their own hands and those of their families. But the majority of the Afrikaners are no more prepared to give up the surplus value – that is, the profits – which they make out of their African labourers, than they are to abandon their ownership of the land to the Africans. “On the farms you hear sad tales of how difficult it is to keep Africans, even with the help of legislation, from drifting away to make rather more money in urban employment. No one at these managerial levels suggests that his workers – or he – would be better off if there were a trek back to the Reserves. On the contrary, the cry is for more cheap labour.” (The Times, 14/1/55: succeeding references are also to The Times). The Nationalists, then, are in a dilemma. They swept triumphantly into power on the cry of apartheid: they captured 86 of the 156 seats in the South African Parliament in 1948, and in 1953 they increased their members to 94. But even their own supporters would not tolerate them if they ever seriously tried to put apartheid into effect.

Big business

The Nationalists must also, when they are considering apartheid measures, reflect upon the opposition they would arouse among the English-speaking element in the Union. Although this element is now split among the United Party, the Federal Party, and the Liberal Party, it remains very powerful; for it contains within its ranks the owners of the country’s industries. The Times correspondent, coming from a country where the capitalist class and the ruling class are merely two names for one body of people, found this distinctly odd. “The situation is a somewhat curious one in which a Government and those who have voted it to power play relatively little part in the conduct of big business . . . It remains true to say that the bulk of the business in the Union, especially at its directorial and managerial levels, is carried on by men of British stock or by other non-Afrikaner immigrants. The Afrikaner now governs; the minority makes the money in the towns.” (14/1/55). Curious or not, it is the fact; and the capitalist class gains more importance with every year that passes. “By 1939 South Africa was well advanced along a course from which, so far as can be seen, there is no turning back, and which was transforming her from a land of primary producers and gold and diamond miners into a complex society in which secondary industries were looming more and more large. The process was accelerated by the war-time hold-up leading to demand for consumer and capital goods. Major industries were established or extended.” (11/1/55). Industrial expansion means larger towns and more workers in the factories. If we take four of the largest cities in the Union, Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban and Port Elizabeth, we find that between 1936 and 1946 the white population rose by 29%; the Cape Coloured population by 34%; the Asiatic population by 38%, and the Negro population by 71 % .Recently Mr. Hepple. a South African M.P., speaking in Parliament, said that in 1936 there were only 175.000 Negroes in industry now there are 500.000 – nearly three times as many (9/2/55).

Hands off our workers

The South African capitalist looks on the Negro not as competitive but as complementary. Already many Negroes have been drawn into industry as wage-workers; and those who have not form a valuable reserve on which to draw for future expansion, and to use as a threat in order to keep down wages. To the factory-owner in Cape Town or Durban, to the shareholder in the Rand mines or the Port Elizabeth car-assembly-works, Negro labour is an essential ingredient in his profits. He is, therefore, resolutely opposed to the Nationalists’ schemes for apartheid.

The Government, although theoretically committed to apartheid, is thus faced with the fact that its opponents regard it as anathema, and that its own supporters are unenthusiastic about translating the ideal into the practical. Few whites are prepared to attack separate seating in buses or separate queues at the Post Office counter; but serious measures of apartheid have a much more mixed reception. Even the removal of Sophiatown Natives to a distance of no more than 11 miles outside Johannesburg, with rail transport available to bring the workers into Johannesburg, has roused much hostility in English-speaking circles. British capitalists sympathised with South African capitalists over this interference with “their” workers, and British workers were able to enjoy the spectacle of the English Conservative Press apparently defending the rights of the South African workers.

Stagnation of Industry

In all their many years of power, the Nationalist Government have only produced one serious plan for apartheid. In the western part of Cape Province, the numbers of Negroes have increased since 1921 from 30,000 to 178,000. But in this area of South Africa there was already a large population of Cape Coloured people. If apartheid was possible anywhere in South Africa, a start might be made on it here – so the Government reasoned – because even if the Bantu were removed, there would still be Cape Coloureds to do the work. Even this scheme, it will be noted, is not full-blown apartheid: for even if all the Negroes were forcibly ejected from western Cape Province, the whites would still rely on the Cape Coloured population; the Government did not dare propose that the Cape Coloureds too should be sacrificed to “apartness.” As could have been expected, the plan came under heavy fire from the industrial interests. “The long-term Government plan for the removal of Africans from the western Cape, which was announced on Friday by Dr. Eiselen, the Secretary for Native Affairs, has received a hostile reception from the spokes- men of industry, which depends heavily on native labour. …The Cape Times today attacks the proposal on the ground that it is impracticable, as commerce, industry, and agriculture, are too dependent on African labour . . . Natives at present do nearly all the unskilled labour in the western province . . . The Cape Times also argues that, if the new policy is seriously implemented, it must be accompanied by a control of industry as drastic as in any totalitarian country to avoid increasing labour needs” (18/1 /55). In Parliament a former Minister for Native Affairs strongly attacked the Eiselen plan “as impracticable and likely to depress the living standards of both Coloured and Europeans, through the stagnation of commerce and industry” (21/5/55).

Where can it be done?

What was even more significant was that the proposal, although it was for only partial apartheid in only one part of a single province, and although the long-term nature of its implementation was stressed by Dr. Eiselen, received nothing more than lukewarm support from the Nationalist Party newspaper itself, Die Burger. Die Burger, the Nationalist newspaper, applauded the plan, but did not gloss over the difficulties. “Let us not be under any illusions.” it said. “The natives are here because of the economy of the western province as it has evolved, and, as it is today it needs their labour . . . Die Burger sees this matter as an important and perhaps decisive test of apartheid. There are fewer Africans in the western Cape than elsewhere in the European areas, and the western Cape has a large coloured working population. If the plan to reduce the number of Negroes here fails, where is South Africa, Die Burger asks, can it be done, and what then of the policy of progressive territorial separation?” (18/ 1/55).

The Nationalists receive electoral support not only from the Afrikaner farmers, but also from the “poor whites” in the towns. These failures of white society listen eagerly to a party which proclaims that, low as they are, they can still look down on men of a different coloured skin.

And those of them who work for wages fear that the Negroes will soon be able to do their jobs for less pay. With these people “apartheid” is a valuable rallying-cry for the Nationalists. But the landed interest is the mainstay of the Nationalist Party, and in the long run determines its policy.

In these circumstances it seems probable that thorough-going apartheid will remain a word on the Nationalist banners rather than an item of their practical policy, just as in this country the Conservative Party, while remaining theoretically opposed to all nationalisation, nevertheless makes no effort to restore the coal mines and the railways to their private owners.

Education

The difference of opinion between the landed class and the industrial interest over apartheid or the lack of it is then, perhaps, more apparent than real. But there are other issues where the two classes are divided by a deep gulf. Whereas the Afrikaner farmer will not hear of African ownership of land outside the Native Reserves, the capitalist has no such objection to it. Indeed, a worker who feels he has a stake in the country by his ownership of his house and garden is a better worker than the completely propertyless man. He is rooted to one spot, and is less likely to go off to leaving his employer with the trouble of training a successor. He can only buy a house with the help of a mortgage, and a worker who has regular repayments to less likely to go on strike than one who hasn’t. On this question, then, there is a clear division of opinion.

But the self-interest of the two classes is most clearly in opposition in the sphere of education. In the eyes of Afrikaner the Negro is and must remain merely a hewer of wood and drawer of water; he should have the very little needed to fit him for his task, and no more. For education would lead him to consider himself as good as the Afrikaner, and would tempt him to agitate for a share in the land of South Africa more in keeping with his numbers. But the Britisher sees the Negro as a workman at a modern factory bench or conveyor-belt; and modern methods of production need skilled and educated workers. Which view is to prevail? In the long run, there seems little doubt that capitalism’s inevitable demand for educated workers will become more vocal and will eventually carry the day; but at present, the Afrikaners seem to be trying to put their theories, in this field at least, into practice. As a start, the Nationalist Government made a determined effort to get all education into its own hands. Under the Bantu Education Act, the subsidies which previous governments paid to high schools and industrial schools were cut by a quarter of their former figure, and may ultimately be stopped altogether (8/ 1/55). The Act is designed to take native education out of the control of the provincial authorities and the English speaking churches and put it into that of the State. In the State-run schools the Bantu will have a “special education” – that is to say, an education which the Afrikaners hope will ensure that they never rise above their present lowly status.

Mr, Strauss, leader of the United Party, indicated that his party might be prepared to accept a compromise on the Native question. “The Native as such,” he remarked in a speech at Bloemfontein, “is not even a homogeneous entity. What is right for the primitive tribesmen in Pondoland may be wrong for the educated and cultured Native professor. What would be necessary for the Native urban worker in Johannesburg would not be desirable for the labour tenant on the Transvaal platteland” (13/ 1 /55). This naive “You do what you want with your workers if we can do what we want with ours” offer, it seems, did not awaken a response among the Nationalists.

Religion

The question of education is bound up with the question of religion. As usual, each of these two contending upper classes has the support of its own churches. The Afrikaners church is the Dutch Reformed Church, of which, it will be remembered, the former Prime Minister Malan, Doctor of Theology, was a pastor. The divines of this Church bend their energies to demonstrate, with the aid of Biblical quotation, how the white man is by nature superior to the black, and how he is thus clearly designated, in the eternal order of things laid down by the Almighty, to rule over him.

This kind of rubbish is refuted by the Anglican and Catholic Churches, which depend for their existence on the support of the capitalist class; they therefore select other Biblical quotations to show that the Bantu, with the help of and under the suzerainty of the particular church concerned, can become a reliable and responsible member of society. In. mid-twentieth-century South Africa this means in effect, that he can become a trustworthy wage-slave. The English speaking churches are supported in this by their brethren overseas: many British clergymen have been able to gain a cheap reputation for liberality by holding forth on the evils of the Nationalist administration in South Africa, while closing their eyes to the exploitation of the workers on their own doorsteps.

Colour and Class

The colour problem in South Africa is not distinct and separate from the other problems which arise inevitably out of a society which is based on private property. Under Socialism there will be no landowner, no capitalist, no poor white, no “worker”: there will be no fear of competition for land or for jobs, no fear of a rival class, no fear of loss of dividend, and therefore none of the hatred to which these fears give rise. When South Africans understand and want Socialism, their hatred for persons of a different colour will disappear; for no man, black or white, can continue any longer in his hatred when he understands the real reasons for it. To treat the colour-bar as an issue outside of and beyond the class-struggle, and to believe that it can receive any real solution while the class-divisions in society remain unsolved, is to stultify oneself at the very outset. The answer to South Africa’s problems is the same as the answer to the problems of Britain, America. Russia: it is the introduction of a Socialist system of society.

WHY SOCIALISTS OPPOSE THE LABOUR PARTY

The Socialist Party of Great Britain is, and always has been, opposed to the Labour Party. We are often asked why. People who think that the Labour Party has Socialism as its aim cannot understand how the Socialist Party can be hostile to the Labour Party. And when we explain that the Labour Party’s aim is not at all what we mean by Socialism, they are still not satisfied. They say that, even if this is true, how can we be opposed to all the praiseworthy and progressive things the Labour. Party is trying to do; why don’t we give them a helping hand?

The answer to this question lies in a difference of theory about human society, and in particular about the capitalist social system in which we live. The Socialist Party holds one theory and the Labour Party holds a quite different one. Is capitalism a system of society with economic laws that regulate its working and limit the policies and actions of governments – as Socialists hold – or is it a mere chance mixture of “bad” and “good” institutions that can be improved at will by any government that wants to do so – as the Labour Party believes?

Capitalism is a System

We hold that capitalism is a system, not a chance collection; that it is based on the class ownership of society’s means of production and distribution, with the working class living by selling its labour-power for wages or salaries and the capitalist class living by owning, their income being derived from the sale at a profit of the commodities produced by the working class, but not owned by them. This is the framework within which governments of capitalism operate, their concern all the time being with ways and means of keeping capitalism running as smoothly as maybe so that the making of profit can proceed, for if it fails capitalism comes to a standstill.

The Labour Party as a whole has always rejected this view. It holds that a Labour Government can do what it likes; that it only has to draw up plans for reforms, get them endorsed by the electorate and then put them into operation. This has all the appeal of a seemingly simple, commonsense, practical and direct approach to social problems; more attractive than the

Socialist Party’s insistence that a new and better social system can only be built on a new foundation, that is by replacing the class ownership of capitalism by common ownership and by replacing the production of commodities for sale at a profit with the production of goods solely for use, without either profit or sale.

The one thing wrong with the Labour Party theory is that it is unsound. Not that they have not tried to carry out their programmes, but each measure introduced has failed to work in the way intended; and the whole lot add up to a superficial tinkering with the system that leaves capitalism essentially unchanged and unweakened.

Nothing has turned out as the Labour Party expected it would. Hence the disillusionment and apathy rife in that Party’s ranks, the growing despair of the possibility of progress at all, and Earl Attlee’s admission, “We are nowhere near the kind of society we want. We have an infinitely long way to go . . . – (Daily Herald, 6/6/55.).

Let us examine the record of the Labour Party. In every field its earlier lofty aims have been whittled down, distorted or forgotten. For decades it claimed to be anti-Liberal and anti-Conservative, anti-war and anti-conscription, but it has supported two world wars as part of a Coalition Government alongside the Liberals and Tories. It preached disarmament but built the Atom Bomb and supported the H-Bomb, and achieved the sorry distinction of being the first British Government for a 100 years to impose conscription in times of peace.

It said it would support higher wages, but was the initiator in 1947 of the policy of “wage restraint” now carried on by the Tories. It promised confidently to reduce the cost of living, but its years of office saw prices steadily rising, including the deliberate act of raising them through the devaluation of the pound in 1949. It opposed the use of troops in strikes and then used them itself and prosecuted strikers who, in 1950, struck in defiance of an old Act of Parliament.

Of course, to all these charges, Earl Attlee would reply that he and his colleagues could not help themselves; they did not want to go to war, impose conscription, put up prices and restrain wage increases, but were forced by circumstances beyond their control. It is, indeed, true that a Labour Government that takes on the administration of capitalism (having no mandate to introduce Socialism) has not much choice about how it does the job. To every well-meaning proposal to do something because it is sensible and in the interest of humanity capitalism retorts that “the system” will not allow it, as indeed it will not. At the present time world markets are overshadowed by enormous quantities of unsaleable wheat and other food products held in store in the U.S.A., Canada and Australia. Since half the world’s population are undernourished, common sense would suggest giving it away or selling it cheaply, but the proposal of the American Government to do this was met with panic protests from Canada and elsewhere; for if the American Government gives the stuff away it will close the market to Canadian and Australian wheat and threaten ruin to farmers in those and other countries.

Because we live under capitalism the most useful and serviceable thing the American Government could do would be to burn the lot or dump it in the sea and keep agriculture prosperous by encouraging the farmers to grow some more; until that too has to be destroyed.

There used to be a demand in Labour Party circles for “work or full maintenance” for the unemployed, on the face of it a reasonable demand, but one which is now never heard of. It was socially reasonable but capitalistically impractical, for if the unemployed could get as much as those at work capitalism would break down.

In the matter of profit the wrong theory of the Labour Party misled them in an almost unbelievable way. They thought they could “take the profit out of capitalism” either by limiting profits and dividends or by nationalisation. Nothing would convince them of the truth that profit is the driving force of capitalism, without which it runs to a stop. The Labour idea was as meaningless as to talk of taking the explosive out of dynamite or the alcohol out of whisky. In practice therefore they had to have their nationalised undertakings run on profit-making lines, and had to drop the idea of abolishing profit.

At one time, too, they were all in favour of equalitarianism and the abolition of the contrasts of riches and poverty, but capitalism, while they were in office, taught them the absurdity of supposing that you can run capitalism on equalitarian lines The Communists in Russia have kept pace with the British Labour leaders in the flight from equalitarianism, and for the same reason.

All along the line it is the same experience. The attractive ideal of the reformer goes through the mill of capitalist legislation and comes out as an unlovely pillar of the capitalist system, so that the last state is no better than the one before; the unorganised private charity and workers self-help schemes of the 19th century have been replaced by the cold-blooded monster known as the National Insurance scheme, with its law-enforced contributions, its mocking pretence of adequately meeting needs, its incomprehensible maze of regulations barring claims, and its fines and imprisonment for non-compliance.

If the reformists are not swept away by the growth of the Socialist movement the next 50 years will be spent on the campaigns of rival parties for pettifogging reforms of that reform.

As was argued by the Socialist Party half a century ago, if the capitalist class were faced with the growth of a powerful movement for Socialism among the workers they would fall over themselves to offer reforms in an endeavour to stave off the end of their system.

As it is, new evils crowd on us faster than the reformists can patch up. The unsolved and much increased problem of the “slums and the millions of decaying houses (incidentally partly the result of that other reform, rent control), greets the new demand for reform of the housing subsidy reform; and after generations of trade union struggle for shorter hours and earlier retirement and against piecework, shift-work and night work, the Labour Government while in office gave support to the opposite of each of these demands. One reform put forward by the Labour Party in 1956 was the reduction of conscript service from two years to 18 months; while the Communists outbid them by supporting conscription !or one year only. It was the Labour Government that made it 18 months in the first place and then increased it to two years; and both the Labour reformists and the Communist reformists in 1939 were against conscription altogether (except, of course, that the Communists never condemned conscription in Russia).

The truth is that capitalism leaves little choice in the way it has to be administered. It is not the good intentions of the Labour Party supporters that are at fault, but their erroneous theory that they can remould capitalist society to their hearts desire. Capitalism is a system; it can be replaced by another system, Socialism, when the majority want it, but it cannot be worked in a manner foreign to its nature. Capitalism is not growing into Socialism, nor can it be made to.

Those who waste time and energy trying to make it do so stand in the way of the movement for Socialism.

THE MATERIALIST CONCEPTION OF HISTORY

When Karl Marx formulated the Materialist Conception of history he gave us a key to unlock the door to a chamber of horrors – the sordid basis of high-flown sentiments. He showed that, since the passing of tribal society, history had been a record of the struggles of different classes to control the social wealth; that the grouping into classes originated out of the way wealth was produced and distributed in each period: that the shape of the main ideas of a period can only be explained by the economic conditions of the time. Further, that class struggles will only disappear when clashing interests have been reduced to one interest; that is, when all forms of private ownership in the means of production have been replaced by the common ownership of the means of production. Thus society was shown to be subject to the general law of evolution, though the artificial environment with which man has surrounded himself makes differences in the particular way the law operates in human society as compared with the animal world.

Before Marx’s time history appeared in a fortuitous light; as the operations of Gods or devils, heroes or scoundrels, clever men or fools or knaves. The Materialist Conception of History made clear that history was a natural development in accordance with certain definite laws; that it consisted of a chain of fundamental changes in which each new epoch sprang out of the previous one, but with a different economic base, a different grouping of classes, and a corresponding difference in the general outlook of the time.

This does not mean that each epoch produces a completely new set of ideas. Old ideas are modified by the new mould and some fresh ideas are developed. For example, sporting contests of all kinds have existed for as long as there are any records, but sham-amateurism is a product of modern commercialised sport.

Likewise similar economic circumstances produce similar ideas and similar solutions, even though thousands of years may intervene. This accounts for the fact that many things that appear to be the special product of modern times have, in fact, been thrown up at different times in the past; like the grain dealers of Athens, who were prosecuted for black-marketeering, or the nationalisation schemes of Xenophon two thousand years ago for the purpose of increasing Athenian revenues, or the Government of Ferrara in the 15th century, which bought and distributed corn as well as monopolising fish, salt, fruit, meat and vegetables. Of course, none of these operations were described at the time as Socialistic. That could only occur in a capitalistic society where supporters of capitalism wished to throw up a barrier against revolution, or bankrupt reformers needed to delude their followers into believing that they had found the road to comfort and security.

In spite of “full employment,” gambling on the pools, and T.V. sets on the hire system, sooner or later the mass of the population, those who are compelled to work for a living, will be driven by their material interests to set about abolishing the private ownership of the means of production and replacing it by the common ownership of the means of production. In other words, converting all that is in and on the earth into the common possession of all mankind. And this will be in accordance with the Materialist Conception of History’s own decree and in spite of the delusionists’ conceptions.