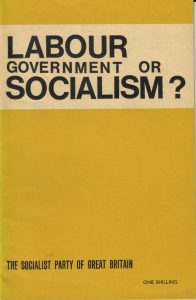

Foreword

Foreword

This pamphlet tells you what socialists think of Labour government – not only the Wilson government which entered office in 1964 but all Labour governments past, present and future.

The Socialist Party of Great Britain has a distinctive point of view on this. You will not find in this pamphlet the kind of criticisms that abound in the Press and in trade union circles, based on disappointment that the Government has not done as well as its supporters hoped it would do, or giving advice to the Ministers about the policies they ought to follow. We have no hope in Labour governments or advice to offer to them: we do not hold that if they had been led by other men or had thought up other policies the outcome would have been significantly different. As socialists, our interest is in the vital issue of changing completely the economic structure of society. If the existing economic and social arrangements continue it is a matter of small account whether the administration is Conservative, Labour or Liberal.

Many people, seeing this, have come to believe that ‘political parties are all the same’ and that ‘politics is a sham’ and not worth while. Nothing could be more mistaken. Politics which consists of sitting back waiting for Party leaders to put things right – that kind of politics is indeed useless; but political action directed to achieving in a democratic way a fundamental change in society is a very different matter. Socialism is worthwhile and can be achieved. We ask you to read this pamphlet to find out why and how.

Executive Committee

SOCIALIST PARTY OF GREAT BRITAIN

February 1968

Chapter One – Earlier Labour Governments

Chapter Two – A Word to Labour Voters

Chapter Three – ‘Making Capitalism Work’

Chapter Four – Labour Government Wage Restraint

CHAPTER ONE

Earlier Labour Governments

MacDonald, 1924

Government by the Labour Party in Britain has a long history; the first such government having been in office from January to November 1924. It came as the result of the failure of the Conservatives to win a clear majority for a programme of protective tariffs at the general election in December 1923. With 258 MPs the Conservatives were still the largest of the three parties. Labour having 191 MPs and the Liberals 159. The Labour Party had campaigned for Free Trade to which they had long been committed, as also had the Liberals. By agreement between Conservative and Liberal leaders the Labour Party became the government but with some outsiders in its Cabinet, including a Conservative peer, Viscount Chelmsford, in charge of the navy.

That Government, with Ramsay MacDonald as Prime Minister, could not pass legislation without the support either of the Conservatives or of the Liberals; and when in October 1924 these two combined against it, the Government had no choice but to appeal again to the electors.

Although the Labour party pleaded that it had been ‘in office but not in power’ and claimed to have done well in the circumstances, the election was an overwhelming victory for the Conservatives: the Labour Party lost 40 seats and the Liberals three-quarters of the seats they had held.

Some of the Government’s actions came under criticism from within the Labour Party, including the building of five new cruisers (which the Liberals opposed), the bombing of tribesmen in Iraq, and firing on strikers in India – those two countries being still under British rule. At home the Government ran into trouble with strikers and had made all preparations to declare a state of emergency if a strike of underground railwaymen had not been called off.

Unemployment was well over the million mark throughout the year. The numbers out of work fell a little, continuing a downward trend that had operated since 1921. Prices rose a little in spite of government measures which were supposed to lower them, and wages rose slightly more than prices.

Even its most loyal supporters did not claim that the first Labour Government had been much of a success, but there was worse to come a few years later.

The Second MacDonald Government, 1929-31

The second Labour Government entered office in June 1929 under the same Prime Minister. It was to end in internal dissension and electoral disaster which left their mark for years.

Like the first it was a minority government, the strength being Labour 287 MPs, Conservatives 260 and Liberals 59, the difference being that this time Labour was the largest party; with Liberal support, or with Liberal abstention, it could out-vote the Conservatives.

At the general election which gave them a second chance the Labour Party had given prominence to the action the Government would take to reduce unemployment – then standing at 1,164,000. It also undertook, if returned with a majority, to nationalize the coal industry and to introduce measures to reduce food prices, develop and modernize industry, and deal with the efforts of trusts and combines to raise prices. The Prime Minister set up a committee of ministers, including Sir Oswald Mosley, to deal with the unemployment problem and an advisory council consisting of economists, industrialists and others to advise him on economic problems. But instead of falling, unemployment started to rise. Within a year it had gone up by 750,000 to 1,911,000, and in two years it had more than doubled, at the record level of 2,707,000.

In the summer of 1931, following banking failures on the Continent, there was a drain of gold from London and the Government hurriedly discussed economy measures to ‘save the pound’.

Seeking fresh loans in America they were told that the New York bankers ‘would only help if they were sure that the Government was taking sufficient measures of retrenchment to restore confidence on orthodox lines. This meant, in fact, cuts in civil service pay and in the pay of the forces, and also in unemployment benefits (Henry Pelling, Short History of the Labour Party. 1961, p.67).

Some members of the Cabinet refused to agree to the cuts in unemployment pay, as also did the T.U.C. and the Labour Party National Executive. The upshot was that the Labour Prime Minister formed a National Government along with Tory and Liberal leaders, and the Labour Party was split in two.

Mosley, later to form a Fascist organisation, had already resigned because the Government did nothing about his Committee’s proposals for unemployment. Although the National Government had declared its intention of ‘saving the pound’ (a policy which the Labour Opposition opposed), it went off the gold standard within a month of taking office by suspending the obligation to sell gold at a fixed price.

In the two years the Labour Government had been in office, 4 million workers had had their wages reduced, including the Government’s own employees.

Prices had indeed fallen but this was the result of world depression. Far from welcoming it, the Labour Party at its Annual Conference in October 1931 adopted the policy of seeking to prevent a further fall. At the general election in October 1931 the Labour Party lost 1,750,000 votes and had its parliamentary strength reduced from 287 to 52.

It was to take 14 years and another world war to give the Labour Party its third term of office.

Attlee 1945 -51

The election held in July 1945 gave the Labour Party what it had lacked before, a clear majority of 393 MPs in a House of 640. This time there could be no plea that the Opposition was preventing the Government from doing whatever it wanted to do.

A vigorous programme of nationalisation was carried through covering the coal mines; the railways and most road transport; the gas and electricity industries; the Bank of England, cables and wireless and iron and steel. The Labour Government introduced the National Insurance and National Health services, repealed the Trades Disputes Act of 1927, and withdrew from India and other colonies.

While the first two Labour governments had to face heavy unemployment, the third was lucky in having almost continuous very low unemployment; but this brought its own problem – that of preventing the workers from pressing for higher wages than the Government wanted. The Government’s answer was the policy of ‘wage restraint’ associated with Sir Stafford Cripps, Chancellor of the Exchequer.

One of the Government’s promises had been to keep prices stable but during their six years of office the cost of living rose by 30 per cent. Inevitably the Government came into collision with strikers and, within a few months of taking office, troops were being used to unload ships during a strike of dockers. In Opposition the Labour Party had condemned the use of troops in industrial disputes.

In 1949 a financial crisis and run on the pound developed, similar to that which led to the split in the Labour Party in 1931, and to the devaluation crisis in 1967. After a dozen declarations that the pound would not be devalued, devaluation by 30 per cent was announced.

The Labour Government started to build the British atomic bomb and the hydrogen bomb. On 24 October 1949 Mr. Attlee announced that the Government proposed to make a charge not exceeding 1s for each National Health Service prescription and power to do this was taken in the National Health Service (Amendment) Act, 1949. The charge, however, was not imposed until 1952, by the Conservative government.

In 1951 the Labour government passed a further Act imposing charges for the supply of Health Service dentures and spectacles. Bevan and Harold Wilson, who had accepted the decision to charge for prescriptions, refused to agree to the charges for dentures and spectacles and resigned from the Government; these charges were continued under the 1964 Wilson government.

Tenure of office had again created dissension in the ranks of the Labour Party, and the Government’s measures failed to secure sufficient support among the electors to give it a further lease of life. The swing of support towards the Conservatives was small, and indeed they got less than a majority of votes; but the outcome was that Labour Party strength in Parliament was reduced to 315 at the election in February 1950 and to 295 at the further election in October 1951.

Then began thirteen years of Conservative Government.

CHAPTER TWO

A Word to Labour Voters

After the 1945 General Election which swept the Labour Party into power, a Labour MP summed up the aim of his party as ‘full employment, all-round national prosperity, international concord, health, homes and happiness for the whole people’. Of course, the Conservatives and Liberals would have claimed that this was their aim too; but the voters had decided, as they did again in 1964 and 1966, that the best chance of getting what they wanted was from a Labour Government.

Why then are so many Labour voters disappointed? Why is there a swing to the other parties at by-elections? Why do more and more people not trouble to vote? Why do so many people become cynical about politics and say that nothing makes any difference? Why have some trade unions that are affiliated to the Labour Party threatened to withhold contributions and to form an independent ‘trade union party’?

They are disappointed because they did not expect that under Labour government there would be a big increase in unemployment, higher charges from the nationalized railway, electricity and gas industries, and the Post Office. Nor did they expect a ‘wages standstill,’ higher rents and mortgage charges, and continued preparations for war and support of American capitalism’s aims in Vietnam.

The Socialist Party of Great Britain claims that it is not political action which has failed but – a very different matter – the kind of political aims pursued by the Labour Party. Many different groups of people went into the Labour Party when it was formed at the beginning of the century. Trade union leaders wanted political action to secure alterations in the law governing trade unions. Social reformers thought that a separate political party was the best way to get legislation on old age pensions, unemployment and sick-pay schemes, and acts to promote the building of houses at low rents. They were joined by supporters of nationalisation and municipal enterprise, and advocates of peace and disarmament; also, of course, there were some who saw the chance of furthering their political careers. The Labour Party at its formation made no pretence of being a socialist party.

It was, however, supported by some who called themselves socialists. Keir Hardie, for example, who argued that the Labour Party could be gradually changed into a socialist party and that nationalisation, while of no use in itself, should be supported because it would, he thought, provide the kind of centralized structure which would be there to be taken over by a future socialist social system.

From its formation the Socialist Party of Great Britain held these claims to be fallacious and was convinced that a party so constructed could never become socialist or help the socialist movement.

The socialist case against the Labour Party was and is that the problems of the working class cannot be solved by administering capitalism but only by replacing it with Socialism. That this requires the winning over of the workers to an understanding of Socialism, and democratic socialist political action to gain control of the machinery of government for the act of establishing a fundamentally different social system. Capitalism, with its inherent class struggle and wars, cannot be made to meet human needs. The Labour Party started with the idea of reforming capitalism and ended in the Labour Government being just another government of capitalism with a different name, absorbed in dealing with capitalism’s problems and contradictions.

Because of their opposition to the Labour Party socialists were called ‘impossiblists’, charged with delaying the victory of Socialism, and told to watch how the policy of Labour Party ‘gradualness’ would prove swifter in the end. Capitalism has not been changed in essentials.

Labour governments have not ended the evils of poverty, unemployment, and strikes and the threat of ever more destructive wars is with us still, and Socialism has yet to be achieved.

The Labour Party pays lip service to Socialism but it conducts itself in office in precisely the manner that socialists foretold it must do. Labour governments are no more than an alternative to the Conservative Party as administrators of capitalism.

That this is so has been stated explicitly by a former member of the Wilson government and member of the General Council of the TUC:

‘Never has any previous Government done so much in so short a time to make modern capitalism work’ (The Rt. Hon. Douglas Houghton, MP, The Times, 25 April 1967).

Mr. Houghton was not blaming the Labour government but praising it. In the same article he wrote: ‘Looking now broadly at the Government’s economic and social policies we find a general strategy of impressive range and imagination. Incentives to private investment, Government investment in the private sector, inducements to regional development, subsidized employment in manufacturing industry, and much else’.

Put in its simplest terms Mr. Houghton, along with the rest of the Labour Party leadership, believes that a Labour Government can do a better job of running capitalism than can the Conservatives. This may or may not be true; as socialists we are not concerned to argue about it.

There can be little difference one way or the other because capitalism dictates its own necessities, irrespective of the party label of the government.

We ask the reader to recognize that trying to make capitalism run as smoothly as may be, while it is a natural function for a capitalist party, is not the business of a socialist party as has indeed been admitted by the late Lord Attlee, before he became Prime Minister in the 1945 Labour Government. In his book The Labour Party in Perspective (Victor Gollancz, 1937, page 123),

Attlee explained why the Labour governments of 1924 and 1929, being minority governments dependent on the support or neutrality of the Conservative and Liberal MPs, ‘could only survive by not challenging the fundamental standpoint of their opponents and seeking to secure such changes as could be achieved within the framework of the existing order of society’.

Things would, he said, be different when the Labour Party became the majority party. ‘The Labour Party stands for such great changes in the economic and social structure that it cannot function successfully unless it obtains a majority which is prepared to put its principles into practice.’

He concluded: ‘The plain fact is that a socialist party cannot hope to make a success of administering the capitalist system because it does not believe in it’.

You cannot have it both ways. You may hold with Mr. Houghton that the Labour Government is doing a good job of making capitalism work, or you may hold that that is not a task for a socialist party; but you cannot hold that the Labour Government in so doing is fulfilling the function of a socialist party.

We, as socialists, say that no government can make capitalism work to the advantage of the working class.

CHAPTER THREE

Making Capitalism Work

As the Labour Party is almost entirely dependent on funds supplied by affiliated trade unions, and as the aspirations of most workers are summed up in the desire for higher wages, lower prices and the abolition of unemployment, the Labour Party, even more than the Conservatives and Liberals, has traditionally promised to be the party which would look after these things.

Nothing in the record of Labour governments has so dismayed its supporters as the discovery that the promises have not been kept. In the years between the wars when unemployment was high and wages and prices were generally falling, Labour Party propaganda concentrated on the pledge that a Labour government led by men with the welfare of the workers at heart would plan the economy in such a way that unemployment would be eliminated and the workers’ standard of living raised. There was at that time no need to think also of keeping prices down but this promise was added after the war.

In those days the promise of higher wages always held a prominent place in the Labour Party programme. Attlee, writing in 1935, was confident about this:

‘A Labour Government, therefore, not only by the transference of industry from profitmaking for the few to the service of the many, but also by taxation, will work to reduce the purchasing power of the wealthier classes, while by wage increases and by the provision of social services it will expand the purchasing power of the masses’ (The Will and the Way to Socialism, p.42)

Events have refused to follow the course prescribed in the plans of governments. The policy of keeping prices down has been a total failure, for prices have been rising almost continuously from 1945 to the present time, including the 13 years of Conservative government. The trade unions have been able to push wages up but against a background of ceaseless exhortation by ministers that they should show restraint, and interrupted by periodical attempts by Labour (and Conservative) governments to hold wages down by threats and legislation.

Because for many years after the second world war unemployment in Britain remained at comparatively low levels (except in particular ‘depressed’ areas), the belief grew up that governments, by using the methods popularised by the economist Keynes, had the situation under complete control; but in later periods, 1962-3 under the Conservatives (when unemployment at one point exceeded 900,000), and 1966-7 under the Labour Government, the big increase in the number out of work showed this belief also to be unfounded.

To add to the dismay of Labour Party supporters, Ministers in Labour governments have repeatedly declared their acceptance of the need for the profit earning capacity of companies not to be impaired.

At the 1948 Trades Union Congress Sir George Chester, for the TUC General Council, backed up the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s demand for wage restraint and said: ‘Profit in the form of marginal surpluses was essential to the conduct of industry whether it be nationalized or in private hands. It is inescapable until we can alter the whole structure of industry and replace profit by some other incentive’ (Daily Herald, 10 September 1948).

The same theme was put to the delegates at the Brighton TUC, on 3 October 1967, by Mr. Callaghan, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer: ‘I want industry to be profitable. It is in your interest that industry should be profitable.’

and:

‘I want British industry to be more profitable over the next 12 months than over the last 12 months’ (The Times, 4 October 1967).

For socialists there is no surprise in this. Capitalism operates according to its own economic laws and these laws do not cease to operate because Labour governments pay lip-service to Socialism.

The economic law of capitalism is that all enterprises, whether private or nationalized, are normally operated for profit. If their products cannot be sold at a profit, production is curtailed or brought to a stop. The overriding condition for production to continue is that wages shall not rise to the point at which profit disappears. All governments administering capitalism, no matter what desires the individuals may have or the principles they may profess, base their economic policy on profit making.

If Labour Party leaders do not know this before they take office, the pressure of economic forces soon teaches them.

CHAPTER FOUR

Labour Government Wage Restraint

Capitalism, again in accordance with its economic laws, is incapable of steady growth. It operates in alternate phases of expansion and contraction, alternate periods of falling and rising unemployment; so although ‘wage restraint’ is always a necessity for capitalism, positive government action to enforce it tends to be intermittent. When production declines, wages are restrained by the pressure of unemployment; but when boom conditions obtain and low unemployment enables workers to push up wages, governments step in with policies of wage restraint. In the last 20 years these policies have become more and more elaborate.

Everything done by the Wilson government in the sixties had been tried out first by the Attlee government in the forties. The first step of the Attlee government in 1947 was to call on the workers to work harder: ‘What is necessary is increased production per annum. In attaining this everyone has a part to play: the responsibility does not fall upon productive industry alone. It is as necessary to increase the work done per person in the central and local government services, in public utility and transport services, and in the distributive trades, as it is in manufacturing industries’ (Statement on the ‘Economic Considerations affecting Relations between Employers and Workers’, January 1947).

This was followed a year later by a government declaration that ‘there is no justification for any general increase of individual money incomes . . . each claim for an increase in wages or salaries must be considered on its national merits . . . (Statement on Personal Incomes, Costs and Prices, February 1948). Arbitration bodies were told that they should not depart from this, and no workers were to have their wages increased merely to maintain relativity with the increased wages of some other workers. Exception was made only where the Government considered higher wages desirable in order to attract more workers to particular industries, or where higher wages were accompanied by ‘a substantial increase in production’.

The same restraint was to apply to profits and rents. The concession was made at this stage that if a ‘marked rise in the cost of living’ took place and levels of income thereby became inadequate they would be reconsidered; but in 1949 even this was withdrawn and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Stafford Cripps, declared in the House of Commons, on 27 September 1949, that the rise in prices following the devaluation of the pound was not to be an excuse for higher wages: ‘especially and specifically there can, in our view, be no justification for any section of workers trying to recoup themselves for any increase in the cost of living due to the altered exchange rate’.

The Attlee government’s justification for the policy of restraint was the familiar argument that otherwise British export prices would rise and British goods would be priced out of world markets – familiar because it is the argument used by all governments, at all times and in all countries.

After the Attlee Labour government went out of office a Labour MP, Mr. Richard Crossman (who later became Minister of Housing and Local Government in the Wilson Government), made an admission about the wages policy of the government he had supported: ‘The fact is that ever since 1945 the British trade unionist could have enjoyed a far higher wage packet if his leaders had followed the American example and extorted the highest possible price for labour on a free market. Instead of doing so, however, they exercised extreme wage restraint. This they justified by pointing out to the worker the benefits he enjoyed under the Welfare State – food prices kept artificially low by food subsidies: rents kept artificially low by housing subsidies, rent restriction; and in addition the Health Service’ (Daily Mirror, 15 November 1955).

Mr. Crossman’s point about prices and rents being kept down is answered by the fact that, between June 1947 and the end of the Labour Government in October 1951, the retail price and rent index rose by 29 per cent while the wage rate index lagged behind with an increase of only 22 per cent.

So much for wage restraint under the Attlee government.

The next full-scale try-out of wage restraint was the Selwyn Lloyd ‘wages pause’ under the Macmillan Conservative government in 1962. It is outside the scope of this pamphlet but calls for mention on account of the furious denunciation with which it was greeted by the Labour Party, yet all Selwyn Lloyd was doing was to follow in the footsteps of Attlee and set a model for the Wilson government which was to come after.

When it came it followed the familiar pattern: production and exports must be increased, prices must be kept competitive, incomes had been rising faster than production, restraint is necessary.

It was offered to the electors in a quite different guise, being associated with the 1965 National Plan, described in the Labour Party pamphlet, Target 1970, as ‘an exciting programme for a great national effort to earn and keep higher living standards for everyone . . . The plan aims to achieve a 25 per cent growth in the national output in the next five years . . . Our wage packets will go up. For every £5 earned now there will be an extra £1’. But the National Plan with its assumed annual 4 per cent growth rate never got off the ground and was soon to be quietly forgotten.

What did come was the ‘crisis’; the adverse balance of payments, the run on the pound, the Prime Minister’s reiterated pledge not to devalue, and the call for restraint in order to avoid this. On 20 July 1966, only 16 weeks after the general election, the ‘Prices and Incomes Standstill’ White Paper was issued, declaring an immediate standstill till the end of the year, to be followed by a six-month period of severe restraint. All agreements to increase pay or shorten hours, including agreements to increase pay under cost-of-living sliding scale arrangements, were frozen for six months; and all increases in the first six months of 1967 were subjected to stringent conditions. Similar restrictions were imposed on dividends and rents, except rents of council houses, in respect of which Councils were urged to introduce rent rebate schemes for tenants able to show ‘limited means’.

It was widely, but mistakenly, supposed that the Government was imposing a complete standstill on prices but this was never intended. On the contrary, certain price increases were deliberately aimed at with the purpose of reducing purchasing power.

The Right Hon. Aubrey Jones, the ex-Conservative Minister and Conservative MP, who was appointed by the Labour Government to the chairmanship of the National Board for Prices and Incomes, admitted in evidence to the Royal Commission on Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations that the Selective Employment Tax had a similar purpose. ‘The Selective Employment Tax . . . had as its object in fact to cut back the country’s living standards, because they were rising too fast’ (Minutes of Evidence, 4 October 1966).

The result was that the retail price index continued to rise under the Labour Government, the rise between October 1964 and December 1967 being 12.3 per cent. Rents and other housing costs rose by 17 per cent or 3s. 4d. in the pound.

A further step taken by the Government was the Prices and Incomes Act 1966, requiring wage claims to be notified to the Government within seven days, and enabling the Government to impose a 30-day standstill on agreements and, if so decided, to refer them to the Prices and Incomes Board with a possible further three-month delay. Failure to observe the provisions of the Act is subject to various fines, up to a maximum of £500 for defaulting trade unions.

Experience proves beyond question that the position of wage and salary earners is the same whether capitalism is administered by a Conservative or by a Labour government. Some workers believe that this need not have happened if the Labour government had chosen to follow a different course. The Socialist Party of Great Britain does not take that view. What we have experienced has been the inevitable consequence of perpetuating capitalism.

Within capitalism there is no escape from its economic laws. The Labour Party used to claim that it knew better than the Conservatives how to eliminate industrial disputes and offered nationalisation as a specific remedy but strikes have continued as before, many of them in the nationalised industries. In October 1967 the Cabinet, following the precedent of earlier governments, Conservative and Labour, was considering the proclamation of a state of emergency permitting the use of troops, if a threatened railway strike took place (The Times, 21 October 1967)

In 1931 the section of the Labour party which went into opposition accused the MacDonald National Government of having imposed economies under pressure from American interests from whom they were seeking financial aid.

In 1966, in a similar situation, the same thing happened again – this time under the Wilson government.

‘It became clear yesterday that Mr. Wilson has made his wage freeze more comprehensive and introduced it more rapidly than originally intended, primarily to satisfy President Johnson’ (The Observer, 31 July 1966).

Another demand for the workers to make sacrifices came when the Wilson government’s policy of ‘saving the pound’ went the way of other policies. On Thursday 16 November 1967 the Cabinet decided to devalue by 14.3 per cent. This devaluation followed the same course as in 1949 – first the protestations that they would not devalue because that would be bad for the workers, then the deed, then the pretended discovery that it was quite a good thing after all.

Just before the Attlee government devalued the pound by 30 per cent on 18 September 1949, the Labour party monthly journal Fact published an article explaining why the Government would not devalue:

‘If the pound were devalued to three dollars . . . up would go the price of bread. A similar rise would be unavoidable in the price of every commodity in which raw materials imported from outside the Sterling Area are a part of the cost. Thus, if devaluation succeeded in closing the gap (which is doubtful) it would do so by lowering our standard of living. The pound would buy less in Tooting and Bradford, as well as in New York and Winnipeg. Devaluation is therefore an alternative to wage-slashing as a device for cutting our prices at the expense of the mass of the people’ (Fact, August 1949).

In 1967, only four months before he introduced devaluation, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Mr. Callaghan, had denounced it. He said in a speech in the House of Commons:

‘Let there be no dodging about this. Those who advocate devaluation are calling for a reduction in the wage levels and the real wage standards of every member of the working class of this country .They are doing this and the economists know it . . . This is a nostrum among economists who are quite clear-sighted and cold-hearted about its purpose. Unfortunately it has been picked up by a number of people who clamour for devaluation because they believe that it is a way of avoiding other harsh measures. They are deluding themselves. The logical purpose of devaluation is a reduction in the standard of life at home. If it does not mean that, it does not mean anything’ (Hansard, 24 July 1967, Columns 99 & 100).

On 16 January 1968, following the devaluation crisis, Mr. Wilson announced a number of economy measures to reduce government expenditure. Among them was the re-introduction of charges for Health Service prescriptions. These were first introduced by the Conservatives in 1952, under an Act passed by the Attlee Labour Government in 1949, and were abolished by the Wilson Government when they took office in 1964.

A reduction was made in the building of council houses, and the proposed raising of the school leaving age to 16 was deferred until 1973. Lord Longford, a member of the Cabinet and Leader in the House of Lords resigned from the Government because he disapproved of this delay in education expansion, and twenty-five Labour MPs refused to vote for their government’s measures.

CHAPTER FIVE

Unemployment

There is a thread which runs through all governmental pronouncements on wages, irrespective of the political party in power, and for as long back as capitalism itself. It is that unless wages and prices are kept down the workers will bring suffering on themselves in the form of unemployment.

It is plausible because it is based on a half-truth, the obvious fact that if a company’s prices are higher than those of its competitors it will lose the market to them and may end in bankruptcy. But the purpose is to imply something more. It is designed to make workers believe that if they accept lower wages or refrain from pressing for higher wages when they could, they will escape unemployment.

Experience shows, however, that unemployment exists in countries with relatively low wages as in countries with higher wage levels. In low wage India with its 2,500,000 unemployed, as in high wage USA with its 3,000,000 unemployed. The rises and falls of unemployment go on irrespective of the movements of wages.

In 1921-2 wages fell in Britain by more than a third but unemployment continued for some years at over a million, rising to 2,700,000 at its peak. On the other hand, though wages were rising in the years 1945-58, unemployment in these years was relatively low, rarely exceeding 400,000. Neither low wages nor high wages cause unemployment, nor will high or low wages prevent it.

One aspect disregarded by those who advocate low wages to prevent unemployment is that if a company in one country reduces its prices to hold or to capture a foreign market its rivals abroad endeavour to do the same. Ignoring the way in which capitalism operates and its need to have unemployment, the Labour Party from its earliest days proclaimed its belief that a Labour government could prevent unemployment. The claim was repeated in 1959 by Hugh Gaitskell, Leader of the Labour Party, in the election programme The Future Labour Offers You:

‘The great ideal of jobs for all first became a peacetime reality under the 1945 Labour Government. Under the Tories fear of the sack has returned. Tory Ministers have now had to admit publicly that they deliberately caused the sharp increase in unemployment. In the Tory view, unemployment is the remedy for soaring prices. Labour totally rejects the repugnant idea that the nation’s economic troubles can only be cured by throwing people out of work. The first objective of the Labour Government will be to restore full employment and to preserve full employment. That is the prime purpose of our plan for controlled expansion.’

It was in October 1964 that the Labour Party was returned to power. Unemployment in Great Britain (excluding Northern Ireland) was about 348,000. For some time it decreased, and a year later was 317,000. It was still falling in March 1966 when Mr. John Diamond, MP, Chief Secretary to the Treasury, claimed credit for the Labour Government that while they had been in office unemployment had fallen ‘from 1.6 per cent to 1.2 per cent’. There had at no time, he said, been a large increase in the unemployed, and – ‘That is how we propose to continue doing it’ (House of Commons Report, 1 March 1966, Col. 1231).

But six months later the necessities of capitalism disposed differently and unemployment began to rise. It went up 200,000 in October and November 1966, and in the summer months of 1967 the Labour Government had scored another record, unemployment being the highest in any summer since 1940, and nearly double the number a year earlier. In August 1967, including Northern Ireland, it was nearly 600,000. Unemployment will continue to rise and fall, the present Labour Government being no more able to prevent unemployment than were the governments of the past.

CHAPTER SIX

Impossibility of Planning

The Conservatives have been just as unsuccessful in trying to plan ahead as have Labour governments; but it is the Labour party which has always prided itself on its superiority in the matter of planning. Capitalism is uncontrollable and cannot be planned. There are two main reasons for this. The first is that the volume of production under capitalism is not aimed at knowable magnitudes of human needs for food, clothing, travel, etc. but at the uncertain demands of shifting markets which depend not on what people need but on what they can and will spend. The second reason is that planning cannot be successful unless the people involved are co-operating to make the plan succeed. Under capitalism one class lives by the exploitation of the other, one company is trying to ruin its rivals, and each government is trying, by diplomatic cunning and armed force, to gain advantage over others. How can capitalism seriously plan production to feed the world’s hungry while each government at enormous cost is at the same time secretly planning to use armed forces to gain advantage over its rivals?

Real socialist planning on a world scale to satisfy the needs of the human race will be practicable when capitalism has been ended, but while capitalism lasts planning is a utopian dream. Labour governments which have believed themselves to be in control of capitalist economic forces have, on the contrary, been controlled or directed by them. In almost every field Labour party policy has been altered or abandoned.

The Labour Party was a ‘free trade’ party but capitalism has moulded them into believers in protection. They were all for competition between small-sized firms and against the trend to mergers and monopoly. Mr. J. R. Clynes, a minister in the first Labour government, declared that the Labour Party preferred a large number of small capitalists to a small number of large ones.

Now the Labour government officially encourages mergers of already huge firms so that they can better meet foreign competition. They believed they could plan to have a low rate of interest, held out hopes of a 3 per cent interest rate on house mortgages, and denounced the Conservatives for allowing interest rates to rise. When they entered office in 1964, the bank rate was 5 per cent. One of the first steps of the Labour Government was to raise it to 7 per cent and mortgage rates went up with the bank rate.

In January 1967 the Government arranged a meeting with finance ministers from the USA, France, Italy and West Germany, and they agreed to co-operate so as ‘to enable interest rates in their respective countries to be lower than they otherwise would be’. The Chancellor of the Exchequer said: ‘Interest rates are too high and we aim at a generally lower structure’. There seemed at first to be some result of this agreement and the bank rate came down to 5½ per cent (which was still above the rate before the Labour Government came in) but world interest rates were rising again and the planners could do nothing about it. The Government put the bank rate up to 6½ per cent on 9 November, and during the devaluation crisis it went up to 8 per cent.

Another evidence of the futility of Labour government is the attempt to cover up their failure by seeking entry into the European Economic Community. This was now to be the haven of refuge.

It is one more chapter in the refusal to face reality. The Community is only one large capitalist bloc in place of six smaller ones – capitalist before and capitalist after. It is subject to all the economic problems inherent in capitalism – class struggle, unemployment, war preparations etc. The most tragic consequence of the belief that a Labour government can control and improve capitalism is to be found in that party’s traditional belief that it is a ‘peace’ party. In practice its record is one of continuous involvement in capitalism’s wars and preparations for wars.

Capitalism needs armed force to protect the property and profits of the owning class against the dispossessed class at home, and against rival capitalist groups abroad. Disregard of this betrays complete ignorance of the nature of capitalism. Capitalist rivalries over markets, sources of raw materials, and crucial strategic areas and frontiers engender war. Nothing short of Socialism will end the threat of war.

Thus with peace on their lips the leaders of the Labour party have supported one war after another, from their representation in the Coalition Government in World War I up to their support of the war in Vietnam. They helped with rearmament, maintained conscription for years after World War II – the first peace-time conscription for a hundred years. Their great rearmament programme, started in 1951, was the largest peace-time expenditure in British history. In the Labour Government’s budget of 1967, expenditure on ‘defence’ was to cost more than £2,200 million: and all for what? Certainly not to make the lives of the people more secure – never at any time in history has life been in such peril from the infinite destructiveness of war weapons.

It must be emphasised that there is no possibility that some other men or some other party can eliminate war from capitalism. Capitalist wars are made in ‘normal’ peace-time pursuits. The ‘pacifist’ who supports the export drives of the government, designed to force the exports of some other country out of a market, is preparing the ground for war every bit as much as the man who demands more armaments in order to hold or protect markets. The farcical nature of Labour party policy on disarmament was high-lighted by Mr. Wilson’s creation of two new posts – a minister to look after disarmament matters, and an adviser to assist in selling British-produced arms to Commonwealth and ‘friendly’ governments on the lines of an American super arms-salesman (The Times, 15 July 1965).

The way out is not to be found in trying to humanise war or to improve capitalism but in inaugurating a new and different world social system.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Not for the Timid

So far this pamphlet has been concerned to expose the uselessness of Labour government – the present Labour government and all Labour governments – not on the ground that the leaders have failed at their job but on the ground that the job itself, ‘making capitalism work’, is quite useless to the workers.

Some readers may have gone along with us to the extent of agreeing that capitalism has not in the past served the interest of the workers but still hope that perhaps it will in the future if some ‘better’ leaders are found. Forget it! Leaders cannot provide Socialism for those who do not understand or want it, and those who do understand it don’t want leadership. The situation is not one for despair but for hope and action. Sound action must be preceded by sound theory. This requires thought and thought is not easy – most people are afraid of it.

The fashion of our age is to describe political and economic policies as scientific, revolutionary, dynamic, forward-looking, etc. All party leaders use these phrases – Conservative, Liberal, Labour and Communist. But in fact those who use such oratorical clichés are all of them men of extreme timidity so far as purposeful, self-reliant thought is concerned. Some of them, the Conservatives and Liberals, profess to believe in capitalism; the others, Labour and Communist, profess to abhor it. Yet all have worked to perpetuate capitalism, both those who have called it a ‘property-owning democracy’ a ‘welfare state’, and those who misnamed it ‘socialism’. They do nothing except try over and over again the same old stale, outmoded expedients that have occupied capitalist politicians and economists for generations. We ask you to face the fact that there are only two choices open to you.

You can go on having capitalism, with consequences that ought to be familiar enough. Or you can consider the alternative of a fundamentally different and better social system. But you cannot have both; and you cannot mould capitalism into something different.

What is the socialist alternative? It is a social system in which the population of the world cooperates to supply the needs of all, by production solely for use: no buying and selling, no market, no wages system; no prices, profits, rent; no coercive state, no economic rivalries leading to armament and war.

We ask you not to shirk the responsibility of thinking, by dismissing it as utopian. Technically, that is in terms of powers of productive capacity, it is practicable: it is therefore not utopian.

Is it impracticable because human beings are incapable of co-operation? If that is your view what you really mean is that you personally could not or would not co-operate with other people to build a better, safer world. Or is it that you think you are a responsible person but that the others, including ‘benighted foreigners,’ cannot quite make it? Have you stopped to consider that they may be holding back because they think the same about you?

Joint action by workers in all countries is not an impossible dream. The Socialist Party of Great Britain and its Companion Parties in America, Australia, Austria, Canada, Ireland and New Zealand, and groups in other places, have made a start in that direction. The sooner you cross the mental barrier of inertia which has so far held you aloof and join us in the great task of creating a socialist world the sooner will come the day when, by democratic political action, the workers of all lands will be able to gain control of the machinery of Government and make the establishment of Socialism a reality.