As they happily go about their business of committing crimes, criminals may not be aware that this month the new Criminal Justice Act came into operation. Normally, it would not be worth mentioning the arrival of yet another piece of law in this field, but this is the most far-reaching such Act for a very long time and what is called the criminal justice system is threatened with chaos as the courts, the prisons and the police try to digest the changes brought in by the Act.

As they happily go about their business of committing crimes, criminals may not be aware that this month the new Criminal Justice Act came into operation. Normally, it would not be worth mentioning the arrival of yet another piece of law in this field, but this is the most far-reaching such Act for a very long time and what is called the criminal justice system is threatened with chaos as the courts, the prisons and the police try to digest the changes brought in by the Act.

The very words criminal justice have an interest of their own for they imply that someone who is suspected of a crime has a legal right to be told about the charges against them and to have the truth of them assessed without bias or prejudice by a court which, if it decides the defendant is guilty, will sentence them in the same objective way. If something goes wrong and an innocent person is found guilty, the appeal machinery exists to put the matter to rights. So if you haven’t done anything wrong you have nothing to fear; and if you have done something you will be dealt with fair and square.

So that’s alright, then. Except that that proposition has only to be stated to expose its fallacy. Every day, the courts and the prisons are full of people whose response, if they were told about the essential goodness of the criminal justice system, would be a bitter, hollow laugh. With damning regularity—as in the case of the West Midlands Serious Crimes Squad—evidence emerges which shows that this cynicism is completely justified.

Changes

In any case criminal justice is not something which is consistent. At one time it can mean harsher penalties from the courts, at others more lenient. It once meant that some prison sentences had to be suspended—until another Act decided that that was not just. A few years later it meant the substitution of Youth Custody for Borstal training; more recently it has meant a deliberate policy of keeping younger offenders out of custody. With the new Act, criminal justice means that imprisonment should be reserved for only the most serious offence.

The changes brought about by the latest Act are too numerous to mention here. Some will be welcomed by the more neurotically punitive sentencer, like the combination order (which in practice is not expected to be available as a magistrates court sentence) which combines a period on probation with a community service order. Others may not be so welcome—fixing the size of fines by units, the number of which depends on the seriousness of the offence, multiplied by the “disposable income” of the defendant. The Act is intended to abolish the halllowed custom which encouraged courts to dish out punishment for the offence before them, adjusted to take account of a defendant’s previous offences. So no more shall we hear puffed-up magistrates and judges address the quivering prison-bound wretch in the dock in such terms as “You have an appalling record, which leaves me with no choice but to . . .”. Another part of the Act which is unlikely to be welcomed by the courts is the requirement that people should be sentenced for the offences they have committed—which means not to set an example to others. This should mean the end of that traditional preamble to a sentence which began “There is altogether too much of this going on at present. This court wants the message to go out that it will no longer be tolerated. So we are going to sentence you to . . .”.

There will also be big changes in how the time to be spent in prison is calculated, how much of a sentence is served behind bars and how much under the less obvious, but nevertheless powerful, restraints of licence in the community (of which more later). It is open to question whether in the long term these changes will have any real effect. Whatever parliament says, the courts have usually been able to ensure that the people they send to prison do roughly the time the courts think they should. It has been simply a matter of adjusting the length of sentence to take account of the possibility of early release on parole, or licence or whatever. Finally, there are two requirements of the new Act which will be as ineffective as they are welcome to the ever-hopeful penal reformers. One is the sharper distinction to be drawn between offences against property and those against the person.This is in response to the many recent cases in which property was clearly valued higher than human safety, which is perfectly in tune with the basis of capitalist society and its morality.

It remains to be seen whether courts actually do treat people who have stolen large amounts of money more leniently than those who have injured someone. Another reaction to fashionable outrage is the Act placing a statutory duty on everyone in the criminal justice system, including the police, lawyers and the courts, to avoid discrimination on any grounds such as race or sex. Like “criminal justice’’, that sounds very re-assuring until we remember, for example, the repeated declarations by successive Commissioners of the Metropolitan Police, that racism will not be tolerated in the force—and contrast this with how the police actually behave towards black people on the streets or in the fastness of their stations.

Economy

The reason for the new Act, with its sweeping changes in policy and application, are not difficult to see. Even under a government which time and time again has declared war on crime, the figures for recorded offences climb up and up. Since Thatcher’s coming to power in 1979 there has been an increase from 2,536,700 to 5,276,700 in 1991.The traditional response to this is to impose harsher penalties, in particular more prison sentences and longer ones. There are, however, some drawbacks to this policy.

First of all, prison is a very expensive way of temporarily removing someone from the opportunity to commit crime—or at any rate from the kind of crime which goes on in the world outside the prison walls as distinct from what happens inside the prison. The cost of keeping someone locked up varies from prison to prison but for all of them it costs a lot more than it would to send a youngster to public school. On top of that, the evidence is that prison is not effective in the way it is supposed to be—it does not deter people from crime when they come out. Indeed, through their embitterment, brutalizing, or institutionalizing, or getting a criminal education, it often tends to make them recidivist rather than conformist.

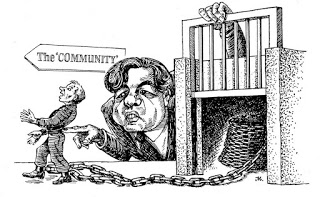

The government’s response to this, after years of Green Papers and White Papers, of “consultation” and “debate”, has been to form the policy of dealing with offenders in the “community” rather than in custody. The motive for this is to save money but it is presented as a policy partly inspired on humane grounds because the very word “community” suggests something warm and caring and supportive. That is why we have Community Psychiatric Nurses whose function now is to treat people in their homes when they should be in mental hospitals if the hospitals hadn’t been cut back or closed in order to save money. We have community centres where mentally bedraggled residents of some ghastly estate where alienation was designed into every pre-cast concrete slab are encouraged to tolerate their intolerable lives. We have Community Service under which people have to do unpaid work to “make restitution to society” for their offences. But if such a thing as “the community” exists it does so as a defensive organism against some of the worst of capitalism’s excesses, or to anaesthetize the systems effects in the delusion that a society based on dividing human beings can have refuges of unity.

But dealing with more offenders in “the community” causes political problems because there are few votes to be gained— and a lot to be lost—by a government seen to be soft on criminals. The Tory government’s wily response to this, in the latest Criminal Justice Act, is to legislate to keep people out of prison except for the most serious offences but then to treat them in a harsher, more controlling, way in “the community”.This has the added advantage of allowing ministers to make kinky speeches about the innate lawlessness of human beings which can only be controlled by the threat of strict punishment. It is no coincidence that the drafting of the Act and piloting of it through parliament was largely the work of the militant Roman Catholic John Patten, who is now venting his vaunted theories about morality on the education system and its children.

In spite of the theories and claims of the politicians, there is no evidence that the level of crime is affected by Acts of parliament or criminological theories or the vote-catching neuroses of politicians. Crime is just another aspect of the society we live under, dominated by a minority class which lives by the parasitic process of stealing from the majority through the exploitation of our wage labour. This theft is perfectly legal—like much of capitalism’s violence against the person—because the parasites have seen to it that there is a huge legal and penal system to make it so, to bring to account anyone who indulges in theft or violence outside the law.

The exploited majority must exist on a lower social and economic level than those who exploit them. Workers in factories and offices are aware of how their social betters enjoy the results of that exploitation, in their sumptuous and glamorous life-styles and their contempt for how the majority are condemned to live. It is not envy which makes workers want to have some of that life-style, but an inevitable struggle to even things up a little. That is what crime is mostly concerned with, for the overwhelming majority it is offences against property and property rights.

In most cases the workers accept their depressed place under capitalism with an apathetic docility, dreaming of ending their misery with a big pools win. In some cases the criminals view it rather differently; theft is a faster, more lucrative way of getting a living and there is always the possibility of the equivalent of scooping the pools—the big tickle. Between these two delusions there is really nothing to choose—and while they persist the ruling class gets on with the more secure and predictable method of legal theft.