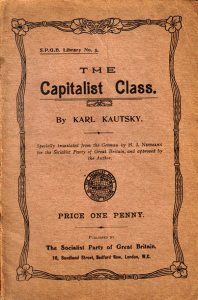

Kautsky on capitalist class (1908)

1. COMMERCE AND CREDIT

1. COMMERCE AND CREDIT

We have seen how the masses of the population in the countries where the mode of capitalist production prevails are more and more becoming proletarians, workers divorced from their means of production, so that they can produce nothing on their own account, and are there¬ fore compelled, if they are not to perish by starvation, to sell their only possession, viz., their labour-power. The majority of the peasants and small traders belong in reality to the proletariat already. What separates them from it in form, their property, is but a thin curtain, hiding, but not preventing, their exploitation and dependence, a curtain lifted and carried away by any strong gust of wind.

On the other side we see a small crowd of property-owners, capitalists and large land-owners, to whom alone belong the most important means of production, the most important sources of sustenance for the entire population, and to whom this exclusive possession gives the possibility and power to make the propertyless workers dependent, and to exploit them.

While the majority of the population is increasingly overwhelmed by want and misery, the small crowd of capitalists and large land-owners, together with their parasites, usurp all the enormous advantages arising from the achievements of modern civilisation, and, above all, from the progress made in natural science and its practical application.

Let us take stock of this small crowd of chosen people and inquire into the part they play in economic life and into the consequences for society arising from it.

We have already become acquainted with the three categories of capital, viz., merchants’ capital, usurers’ capital, and industrial capital. The last mentioned category of capital is the youngest, perhaps not so many hundreds as the other two categories are thousands of years old. But the youngest brother has grown more rapidly, much more rapidly, than the older two; he has become a giant who forces them into subjection and presses them into his service.

Commerce is not an absolute necessity for petty enterprise in its perfect (classical) form. The peasant, like the handicraftsman, can obtain the means of production, so far as he must purchase them, direct from the producer, and he can also sell his product direct to the consumer. Commerce is at this stage of economic development principally of service to luxury, but is on the whole, not indispensable to the continuance of production or to the preservation of society.

Capitalist production, however, is, as we have seen, dependent from the beginning upon commerce just as much as commerce at a certain stage needs capitalist production for its further development. The more this production expands, the more it becomes the prevailing mode of production, the more necessary does commerce become to the entire economic life. To-day it is not alone of service to superfluity, to luxury. The whole production, even the feeding of the population of a capitalist country, depends upon commerce proceeding undisturbed in its course. This is one of the reasons why a world-war at present would prove much more devastating than ever before. War leads to a paralysis of commerce, and that means to-day a paralysis of production, and of the, entire economic life ; it means economic ruin, which extends further, and is not less disastrous, than the devastation on the battlefield.

Quite as important as the development of commerce, has the development of usury become for the capitalist mode of production. Tho usurer during the domination of petty enterprise, was plainly a parasite, who took advantage of the difficulties or prodigality of others and drew their blood. The money he lent to others served, as a rule— as generally the producer already possessed the necessary means of production—for purposes of unproductive expenditure. When, for instance, an aristocrat borrowed money it was to squander it; when a peasant did so it was to pay money taxes or law costs. Lending money at interest was therefore considered immoral and condemned by everybody.

It is different in society with the capitalist mode of production. Money is now the means for fitting up a capitalist concern and for purchasing and exploiting labour-power. When a business man nowadays borrows money in order to establish a new concern or to extend an existing one, it docs not mean (providing, of course, his undertaking succeeds) that he reduces his income by the amount of the interest he pays for the borrowed money. On the contrary, that money is used by him to exploit labour-power, hence to increase his income, and always by a larger amount than the sum he has to pay away as interest. Usury now loses its original character. Its part as a means of taking advantage of financial difficulties and prodigality gradually gives way to the role of fertilising capitalist production, that is to say, of making possible a more rapid development than would take place, if it were to depend on the accumulation of capital based on the means of industrial capitalists alone. Abhorrence of the usurer ceases; he is whitewashed and receives a new, high-sounding name—creditor.

The main direction of the movement of interest-bearing capital has at the same time become a different one. The sums of money which the usurer-capitalists amassed in their coffers flowed in former times from the accumulating centres through thousands of channels to the non-capi¬ talists. But to-day the coffers of usury-capital, viz., of credit institutions, have become accumulating centres, to which through thousands of channels the money of the non-capitalists flows in order that it may from there find its way to the capitalists. Credit is to-day, as of old, a means of subjecting non-capitalists with or without property, to indebtedness to capital on the basis of interest. But it has now also become a powerful means of transforming into capital the possessions of the different sections of non-capitalists, from the enormous wealth of the Catholic church and the old aristocracy down to the few pence saved by servant girls and day-labourers, that is to say, credit has, by transforming these possessions into capital, changed them into a means of exploiting the one and decomposing the other of these sections. The credit arrangements of to-day, savings banks, etc., are lauded because, according to the supporters of the present system they transform the saved-up pence of the wage-workers, handicraftsmen and peasants into capital and these persons into “capitalists.” But this accumulation of non-capitalists’ savings has no other purpose than to place fresh capital at the disposal of the capitalists and thereby hasten the development of the capitalist mode of production, and we have seen what that means to the wage-workers, peasants and craftsmen.

If the credit arrangements of to-day have more and more the effect of transforming the entire possessions of the different sections of non-capitalists into capital, which is placed at the disposal of the capitalist class, they have on the other hand the effect of turning the capital of the capitalist class to better account. They become the accumulating centres of all the money of- the individual capitalists, which these have no opportunity of using for the time being, and make such sums of money, which would otherwise lie idle, accessible to other capitalists in want of them. They also make it possible to transform commodities into money before these have been sold and to lessen thereby the period of circulation, and also the amount of capital which, for the time being, is required for the carrying on of a concern.

Hence it is that the amount and power of the capital at the disposal of the capitalist class increases enormously. Credit has to-day, therefore, become one of the most powerful stinmlants of capitalist production. Apart from the intense development of machinery and the expansion of the army of unemployed, it is one of the main causes of that power of the present method of production which enables industry upon the slightest impetus to rapidly expand.

But credit is far more susceptible to disturbances than is commerce; and each shock it experiences tells upon the entire economic life.

Some economists have considered credit to be the possible means of turning propertyless persons and those owning little property into capitalists. But, as indicated by its name, credit depends upon the confidence reposed by the giver of it in the recepient. The more the latter possesses and the greater the security he offers, the greater is the credit he enjoys. The credit system is hence only the means of obtaining for the capitalists more capital than they possess, the means of increasing the predomination of the capitalists and of accentuating the social contrasts, not of lessening them. The credit system is accordingly not only a means of developing capitalist production more rapidly and of enabling it to utilise favourable fluctuations ; it is also a means of hastening the ruin of petty enterprise, and it is finally a means of making the present mode of production more complicated and more susceptible to disturbances, of also carrying into the midst of tho capitalists the feeling of insecurity and of causing the ground on which they stand to vibrate ever more strongly.

In times gone by a capitalist could not be imagined without a big iron safe, in which he deposited the money coming in and from which he took the money required for making payments. To-day the financial arrangements of the capitalists in the industrially developed countries, especially in England and America, have become the business of separate undertakings—of banks. Payments are no longer made to the capitalist, but to his bank, and are not received from him, but from his bank. And hence a few central concerns deal with the financial transactions of the entire capitalist class of a country.

But if in this way the various functions of the capitalists are consigned to different independent undertakings, they become thereby only outwardly, juridically, independent of each other ; economically they remain as before, closely connected with and dependent upon one another. The functions of any one of the concerns cannot proceed with regularity, if the functions of any one of the other concerns, with whom it stands in business relations, are in any way disturbed.

The more commerce, credit and industry become mutually dependent upon each other, and the more the various functions of the capitalist class fall to separate undertakings, the greater becomes the dependence of the individual capitalists upon the others. The capitalist business of a country—indeed, in certain directions already, of the entire world-market—becomes ever more one tremendous body, whose organs are most closely connected with each other. While the great mass of the population becomes ever more dependent upon the capitalists, the latter themselves become continually more dependent upon each other.

The economic factors of the present mode of production become to an ever larger degree so complicated and sensitive a mechanism that its undisturbed working depends to a continually greater extent upon all the innumerable small cogs of its wheels catching exactly into each other and performing their functions with precision. Never before was there a method of production that so needed regulation according to a plan as the present one. But private property makes it impossible to bring design and order into this system. While the single concerns become economically more dependent upon each other, they remain juridically —from a point of law—independent of one another. The means of production of each single concern are private property, their owner being able to dispose of them as he may think fit.

As production on a large scale develops, and the larger the single concerns grow, so the economic efforts inside each concern become systematised in accordance with a certain precisely thought out plan in every detail. But the working together of the single concerns is left to the blind forces of free competition. By an enormous waste of energy and means, and by increasingly serious upheavals, this competition manages to keep production going, not by putting everybody in the right place, but by demolishing everybody who stands in its way. That is called “the selection of the fittest in the struggle for existence.” In reality free competition annihilates less the incompetent ones than those who are in false places who are unable to maintain their positions through lack of special ability or perhaps for want of capital. But competition is not satisfied to-day with crushing merely those “unfit for the struggle for existence.” The fall of every such “unfit” one causes the ruin or paralysis of many, who stood in economic relations to the bankrupt concern, such as wage-workers, creditors, contractors, etc. Yet to-day it is said that everyone can shape his own destiny. That notion is derived from the time of petty enterprise, when a work¬ man’s prosperity depended upon his own personal qualities—but only his prosperity and that of his family. To-day the destiny of each member of capitalist Society depends less and less upon his personality and continually more upon many and various circumstances, over which he himself has no control. It is no longer a selection of the best which is accomplished to-day by competition.

We have in the previous chapter become acquainted with surplus-value, which is produced by the industrial proletarians and appropriated by the capitalists. We have also observed how the amount of surplus-value produced by each worker is increased by adding to the worker’s labour burden, by the introduction of labour-saving machinery and cheaper labour, etc. At the same time with the development of capitalist industry the number of the exploiters proletarians grows and the amount of surplus-value going to the capitalist class increases by leaps and bounds.

But as, unfortunately, “life’s joys are vouchsafed unmixed to no mortal,” the capitalist class have to divide their surplus-value, although this dividing is most hateful to them ; they must part with portions to the ground landlords and to the State. And the share taken by these two partners grows from year to year.

Under the domination of peasant proprietorship in Europe during the middle ages the peasant owned his farm and agricultural land. Water, woodland, and pasture land were communal property, and uncultivated soil was so plentiful that everybody could be allowed to take possession of and cultivate such land as he had begun to bring into cultivation from the wilderness. Then commenced the development of commodity production with the consequences of which we have already become acquainted. The products of the soil became commodities. That reacted on the soil, which was also made a commodity possessing value. The single peasant communities and associations now endeavoured to restrict the circle of their members, and the latter began to regard the land they owned in common and partly (as in the case of forests and grazing land) also used in common, no longer as common property of the community and therefore inalienable, but as a kind of joint private property belonging only to the existing members and their heirs; property from which all members who subsequently joined the community were excluded. They were desirous of making the land a monopoly. But someone else came to covet the property of the community, namely, the feudal lord, who had been the protector of the common property. If this property in land, that had become so valuable was to be made private property, then he was anxious that it should pass into his possession. In most directions, especially where agriculture on a large scale was developed, the feudal lord succeeded in seizing the peasants’ common property. Peasant-hunting, the driving of some peasants from their homesteads, followed. Nearly all the soil, even that not under cultivation, now passed into private possession: the ownership of land became the privilege of the few. Thus owing to the economic development, particularly to the formation of large property in land, the soil had become a monopoly long before the existing area of cultivation was exhausted, and much before over-population could have been talked about. If, therefore, the land occupies an exceptional position as a means of production because it is incapable of being increased at will, that is not in consequence of all the available soil being already under cultivation, but is due to the fact—at least in civilised countries—that it has already been taken possession of by a minority. There a monopoly of quite a peculiar character arises. While the capitalist class has a monopoly of the means of production, there is within the capitalist class no monopoly of certain means of production by certain members of that class—at least, no permanent monopoly. Whenever a ring of capitalists is formed for monopolising a certain important invention—for instance, a new machine—other capitalists may always come along, who could also purchase this machine, or surpass the same by meariK of a new invention, or imitate it sooner or later. All this is impossible regarding property in land. Landowners have a monopoly not only as far as the non-possessing class is concerned, but also from the standpoint of the capitalist class.

The peculiar character of property in land is developed most acutely in England, where a small number of families bave possession o£ all the land, to which they hold on firmly and do not sell. Who ever requires land obtains the same on lease for a certain rent called ground-rent. (Strictly speaking, “rent” ard “ground-rent” are not synonymous. “Rent” generally includes a portion of interest on capital. For our purpose here, however, “rent” and “‘ground-rent” may be used as identical terms.) A capitalist desirous of having a factory or dwelling-house built, or of establishing a mine or a farm in England, cannot as a rule, purchase the land, but may only rent the same on lease.

In Germany the capitalist is mostly also the ground landlord ; the manufacturer owns the land upon which his factory stands ; the mine proprietor is also the owner of the land in which the pits are sunk ; while the owner of large tracts of agricultural land on the continent of Europe cultivates the same mostly on his own account instead of letting it to a farmer. When the capitalist carries on agriculture on his own soil, when he himself is ground landlord, he need naturally not share his surplus-value with another, But that does not materially alter the case; for he has, generally, only become ground landlord by paying to the previous owner of the farm a capital, the interest on which corresponds to the amount of ground-rent. Hence he pays the ground-rent anyhow, and in the one form as in the other it diminishes his profit.

But the monopoly character of landed property becomes more acute, the stronger the demand for land grows. As population increases, so the capitalist class become more in need of property in land. To the same extent ground-rent grows, that is to say, the total amount of ground rent paid in capitalist Society. The ground-rent of every farm need not increase. A farm yields under otherwise equal conditions the more ground rent the more fertile and the more favourably situated (lor instance, nearer to the market) it happens to be.

Into the laws of ground-rent we can, of course, not enter here. The opening up of new and fertile land can therefore cause the ground-rent of exhausted soil to go down ; the ground-rent of newly opened-up land will, however, only grow so much the more. Thus improvements in the means of transit may depress the ground-rent of a nearly situated area in favour of a more distant one. Both cases have happened during the last two decades. American ground-rents have risen, and indeed (in so far as agricultural protective tariffs have not acted in an opposite direction) at the expense of West European ground-rents. This, how ever, only applies to land used for agricultural purposes. In the towns ground-rent is everywhere rising most rapidly ; for the capitalist mode of production drives the great mass of the population more and more into the towns. Unfortunately, by this aggregation the profit of the industrial capitalists suffers nothing compared with the growing physical and mental degeneration of the toiling masses. And here we encounter the housing of the workers as a new source of their sufferings; but this is not the place to enter into that.

The more the capitalist mode of production develops the keener becomes the antagonism of interests and the more conspicuous grow the contradictions produced; but the more complicated also becomes the entire system, and the greater, too, grows the dependency of one individual upon another, and the greater also grows the need of an authority standing above and charged with making each fulfil the duties arising from his economic function

.

Far less than the previous methods of production can a system so sensitive as the present bear the prosecution of antagonisms and disputes by the autonomy of those immediately interested in the fray. In the place of self-aid enters “Justice,” which is watched over by the State.

Capitalist exploitation is by no means the product of certain rights ; it is its needs that have brought forth and given domination to the rights prevailing to-day. That “justice” does not cause exploitation, but sees to it that this process, like others in economic life, proceeds as smoothly as possible. While we have before described competition as the motive power of the present mode of production, we may regard “State justice” as the “machine oil,” which has the effect of minimising the friction in the capitalist system. The more this friction grows, the more intense the antagonism becomes between exploiters and exploited, between property owners and propertyless ; the larger, more especially, is the slum proletariat; the more does each single capitalist become dependent upon the prompt co-operation of numerous other capitalists for the undisturbed conduct of his concern. So the desire for “justice” for this purpose grows stronger, and the greater grows the need to requisition its organs—law-courts and police, and a strong State force capable of supporting “justice,” if need be.

But the capitalists are not only concerned with being able to produce, buy, and sell undisturbed within their own country. From the start the commerce outside plays an important part in capitalist production, and the more this method becomes the predominating one, the greater appears to be the need for securing and extending the outside market in the interest of the whole nation. But in the world market the capitalists of one nation meet competitors belonging to other nations. In order to oust these they call in the aid of the State, which is expected to demand, by means of the armed force, respect for their claims, or—what is better still—to crush the foreign competitors altogether. As States and monarchs become evermore dependent upon the capitalist class, so the armies cease to serve merely the personal ends of the monarchs, and are utilised increasingly for purposes of the capitalist class. Wars are less and less dynastic, and more and more commercial and national, which in the last instance can only be traced back to the economic conflicts between the capitalists of the various nations.

The capitalist State, therefore, is not only in need of an extensive army of officials for the purposes of law and police (besides, of course, for the administration of its finances), but it requires also a strong military force. Both armies are ever on the increase in capitalist States, but in recent times the military force grows more rapidly than the army of officials.

So long as the application of science had not begun to play a part in the technicalities of industry, the technical aspect of war changed but slowly. As soon, however, as machinery came to dominate industry and subjected the latter to continuous evolution, war machines ceased to be stationary in development. Every day brings new inventions and discoveries, which, scarcely examined and introduced, at great expense, are already superseded by a new revolutionising improvement or addition. And the war machinery constantly increases in extent, complication and costliness. At the same time the progress in the means of transit makes it possible to concentrate an ever larger number of troops on the battlefield ; hence armies are continually increased.

In these circumstances the State expenditure for purposes of war (in which the greater portion of national debts is included) have with all great European powers grown within the last twenty years to an absolutely maddening extent.

The State grows ever more expensive, and its burdens become always more oppressive. The capitalists and large landowners naturally seek (having everywhere the law in their own hands) to transfer the burdens as much as possible from their own shoulders to those of the other sections of the community. But as time goes on there is ever less to be obtained from those sections, and thus in spite of all the trickery of the exploiters their surplus-value has to be encroached upon for the benefit of the State.

We cannot enter here into the details of the reasons for the appearance of this phenomenon, as the comprehension of such supposes some wider knowledge of economics. An example will illustrate the above statement.

Let us take a case of most convincing character. Let us compare a hand-spinner of a hundred years ago, who, we will say, was exploited by a capitalist as a worker carrying on home industry, with a machine-spinner of to-day. How much capital there is necessary to make possible the work of the latter ; and how small comparatively the capital has been which the capitalist used for the purpose of spinning by hand. He paid the wages of the spinner and gave him the cotton or flax to spin. With regard to wages little has altered, but the machine-spinner to-day uses up perhaps a hundred times as much raw material as the hand-spinner; and what enormous buildings, motive power, spinning machinery, etc., are necessary to carry on spinning by machinery.

Yet another circumstance has to be considered : the capitalist of a hundred years ago, who employed the spinner, invested in his concern only the outlay for wages and raw material ; there was scarcely any standing capital—the spinning wheel was not to be reckoned. His capital was quickly turned over—say in three months—hence he only needed to invest and advance in his concern one quarter of the amount of capital he used in the whole year. To-day the amount of capital required for machinery and buildings of a spinning mill is enormous. Though the period of turnover of the amount of capital advanced for wages and raw material may be equal to that of a hundred years ago, the period of turnover of the other portion of the capital, which a hundred years ago scarcely existed, is a very long one.

A number of causes act in the opposite direction, as for instance, the credit system, but especially the fall in the value of products, which is a necessary consequence of the increase in the productivity of labour. But these causes are by no means able to entirely put an end to the development in question. This development proceeds in all branches of industry, in some more, in others less rapidly ; with the result that the amount of capital advanced every year and reckoned at so much per head of the industrial workers, grows rapidly.

Let us suppose that this amount of capital a hundred years ago was £5 and to-day has grown to £50 ; let us further suppose that the exploitation of the worker has increased in the proportion of five to one so that if the surplus-value which a hundred years ago he produced each year amounted to £2 10s., it would to-day, given an equal amount of wages for the year, be £12 10s. The amount of surplus-value has thus in this case, as absolute surplus-value, risen enormously ; but in proportion to the amount of capital which the capitalist invests each year, the surplus-value has fallen. A hundred years ago this proportion was 50 per cent., to-day it is only 25.

That is, of course, only an example, but the tendency explained thereby actually exists.

The total amount of surplus-value produced each year in a capitalist country is increasing continually and rapidly; but more rapidly still increases the total amount of capital invested by the capitalist class in the various capitalist undertakings over which the surplus-value is distributed. If one further bears in mind the fact, which we have already observed, that for the requirements of the State and for ground-rent an ever increasing amount comes out of the total of surplus-value produced each year, one will comprehend that the amount of surplus-value which each year, on the average, falls to a given sum of capital is ever on the decrease, although the exploitation of the worker is growing.

The profit—that is to say, that portion of surplus-value which is left to the capitalist owner of the concern—thus shows the tendency to fall in proportion to the total capital advanced by him ; or, expressed in another way, in the course of development in the capitalist mode of production as a rule, the profit falling to a given amount of capital decreases continually. A sign of this fall is the unceasing decline in the rate of interest.

While thus the exploitation of the worker has the tendency to rise, the rate of profit of the capitalist shows the tendency to fall. That is one of the most peculiar contradictions of the many with which capitalist production abounds.

From this fall in the rate of profit the conclusion has been drawn that capitalist exploitation would end by itself; that capital would finally yield so little profit that the capitalist, in a starving condition, would be seeking something to do. But such would only be the case if the rate of profit would continually fall and the total amount of capital remain the same. That is, however, by no means the fact. The total capital in the capitalist countries increases more rapidly than the rate of profit falls. The increase of capital is one of the presumed conditions of the fall in the rate of profit, and if the rate of interest falls from 5 to 4, or from 4 to 3 per cent., the income of the capitalist, whose capital has in the meantime increased from one million to two or more millions, is not reduced.

The fall in the rate of profit or interest does by no means signify a reduction in the income of the capitalist class, because the bulk of the surplus-value which they obtain increases continually ; this fall in profit reduces the incomes of those capitalists only who are not in a position to increase their capital accordingly. In the course of the economic development the limit is ever extended from which a certain amount of capital begins to suffice for the maintenance of its owner in accordance with his social position. It is an ever larger amount of income which becomes the minimum required to enable anyone, without working himself, to live upon the labour of others. What fifty years ago was still a big fortune, to-day has become relatively a mere trifle. The fall in profit and the rate of interest does not cause the extinction, but merely thte decrease in the numbers of the capitalist class. Every year small capitalists are squeezed out of their ranks and brought face to face with the same death struggle that handicraftsmen, petty dealers, and peasants have to pass through ; a death struggle of a briefer or longer duration, which, however, ends, either for them or for their children, in their merging into the proletariat. What they endeavour to do in order to escape their fate, mostly only hastens their ruin.

One wonders at the great number of stupid people who are induced by swindlers to entrust them with their money on the promise that they will receive a high rate of interest. As a rule these persons are not so stupid as they appear to be : the swindling undertaking is the straw to which they cling in their desire to obtain adequate incomes from their small means. It is not so much their greed as their fear of want that blinds them in that way.

Each step in such progress causes a smaller or greater depreciation of existing industrial machinery or plant, necessitating replacement of them and often extension of the particular industrial concern ; and anyone lacking the capital necessary for that purpose becomes sooner or later incapable of competing and goes under, or is compelled to turn with his capital to some trade in which the smaller concern is still in a position to compete against the larger ones. Thus competition in industry on a large scale causes overcrowding in petty industry, with the result that ultimately, handicraft is ruined even in the few trades in which petty enterprise was hitherto able to meet competition to some extent.

The large industrial undertakings become ever more extensive and enormous. From moderately large concerns, employing hundreds of workers, they develop into gigantic establishments employing thousands (spinning-mills, breweries, sugar factories, iron works, etc.) The smaller undertakings tend to disappear: industrial development leads, from a certain point, not to an increase but to a continual decrease in the number of undertakings on a large scale.

But that is not all. The economic development leads also to the concentration of an ever greater number of undertakings into the hands of a few—either as the property of one capitalist or that of a capitalist association, which economically is only one person (a juridical person).

Several ways lead to that concentration.

One way is the endeavour of the capitalists to exclude competition. In the previous pages we have learnt that competition is the moving force of the present system of production; it is in fact the moving force of the production and exchange of commodities. But although competition is necessary for the entire society of commodity production, each single owner of commodities would like to see his commodities in the market without competition. If he happens to be a possessor of commodities in great demand or of a monopoly, then he is able to raise the prices above the value of his goods ; then those requiring his commodities are entirely dependent upon him for a supply of the same. Where several sellers appear in the same market with commodities of a similar kind, they can artificially create a monopoly by amalgamating and practically forming one single seller. Such an amalgamation—a combine, ring, trust, syndicate, etc., is naturally the sooner possible the smaller is the number of competitors whose opposing interests have to be reconciled.

In so far as the capitalist mode of production causes the extension of the market and the number of the competitors on the same, it makes the creation of monopolies in commerce and industry more difficult. But in every capitalist branch of industry there arrives, as already mentioned, sooner or later the moment, from which its further development leads to the diminution of the number of undertakings in that branch. From that moment the branch of industry developes more and more towards trustification. The time of maturity can be hastened in any given country through safeguarding its internal market against foreign competition by protective tariffs. The number of competitors for this market is thereby diminished and the amalgamation of home producers takes place, thus enabling them to create a monopoly and to obtain a greater share of the wealth produced in consequence of “protection.”

Within the last twenty years the number of combines, by which the production and prices of certain commodities are “regulated,” has, as we know, increased, particularly in the countries of protective tariffs—United States, Germany and France. Wherever it comes to combination the various concerns, which are amalgamated, form practically a concern under one management, they being very often in reality brought under one unified management.

It is indeed, the most important, and from the standpoint of carrying on industries, the most indispensable commodities, namely, coal and iron, whose production, sooner than that of other commodities, falls under the control of combines. Most combines extend their influence far beyond the branches of industry monopolised ; they make, in fact, all the conditions of production dependent upon a few monopolists.

Simultaneously with the endeavour to combine the various undertakings in a certain branch of industry into one, the endeavour grows to amalgamate into one also, various undertakings in different branches of industry, because in some of these concerns tools or raw materials are produced which are required for the carrying on of production in one or other of these various undertakings. Many railway companies possess their own coal mines and engineering works ; sugar factories endeavour to grow a portion of the beet-roots used by them ; potato growers establish their own distilleries, and so on. And there is a third way : that of combining several undertakings into one, the simplest of them all.

We have seen that the capitalist has had to fulfil very important functions under the present system of production. However superfluous these may be under a different organisation of production, yet under the domination of commodity production and private property in the means of living, producing on a large scale is now possible only on capitalist lines. And for that purpose it is necessary, if production is to proceed and the products are to reach the consumers, that the capitalist step in with his capital and apply it advantageously. Although the capitalist does not produce, does not create any value, he plays an mportant part in the present economic relations.

But the larger a capitalist undertaking grows, the more necessarv it becomes for the capitalist to transfer part of his increasing business functions either to the other capitalist undertakings or to his own paid officials whom he employs to carry out some of his duties. It matters nothing from the economic standpoint whether these functions are fulfilled by a wage-worker or a capitalist: they do not become of a value-creating character by the fact that the capitalist has them attended to by someone else, that is to say, that as far as they do not create value, the capitalist has to pay for them from surplus-value. We here get to know a new way of drawing upon surplus-value tending to the diminution of profit.

If the extension of a concern forces its owner, the capitalist, to engage officials in order to lighten his task, the increase in the surplus-value due to the extension recompenses him for that expenditure. The larger the surplus-value, the more of his functions is the capitalist able to transfer to officials, until he has at last rid himself entirely of his managersLap, so that he has left only the “anxiety” of advantageously investing that part of his profit which he does not consume.

The number of concerns that have arrived at such a condition increases from year to year. That is proved most clearly by the growing number of Joint Stock Companies, where, as even the most superficial observer must recognise, the person of the capitalist has already ceased to be of any importance, only his capital being significant. In England 57 Joint Stock Companies were formed in 1845, 344 in 1861, 2,550 in 1888, and 4,735 in 1896. There were 11,000 companies, with a share capital of over £600,000,000 actively engaged in 1888, and 21,223 companies with a share capital of £1,150,000,000 in 1896.

It was considered that by the introduction of the system of share capital, a means had been found to make the advantages of larger concerns accessible to the small capitalists. But, like the system of credit, the system of share capital, which is only a particular form of credit, is, on the contrary, a means of placing the capital of the “smaller fry” at the disposal of the large capitalists.

Since the person of the capitalist can be dispensed with as far as his undertaking is concerned, anybody possessing the necessary capital can embark in industry, whether he understands anything about the particular trade or not. Hence it is possible for a capitalist to own and control concerns of the most varied kind, having perhaps no connection one with the other. It is very easy for the large capitalist to obtain control over Joint Stock Companies. He only needs to own a large proportion of their shares—which can easily he purchased—in order to make the undertakings dependent upon him and subservient to his interests.

Finally, it must be stated that generally, large capital increases more rapidly than small capital, because the larger the capital the greater (under otherwise equal conditions) the total amount of profit, and hence also tli,o income (revenue) which it yields ; again, the smaller the proportion of the profit consumed by the capitalist for his own use, the larger is the portion he is able to add as new capital to that already accumulated. A capitalist whose undertaking yields him £500 a year, will, according to capitalist ideas, be able to live only modestly on such income;. He will be fortunate if he succeeds in putting by £100—one-fifth of his profit—a year. The capitalist whose capital is large enough to yield him an income of £5,000 is in a position, even if he consumes for himself and his family five times as much as the first mentioned capitalist, to turn at least three-fifths of his profit into capital. And if the capital of a capitalist happens to be so considerable that it yields him £50,000 a year, it will be difficult for him, if he is a normal being, to use for his living one-tenth of his income, so that, though indulging in luxuries, he will easily be able to save nine-tenths of his profits. While the small capitalists have to struggle ever harder for their existence, the larger fortunes increase by leaps and bounds, and in a short time reach enormous proportions.

Let us summarise all this : the increase in the size of the undertakings : the rapid growth of the larger fortunes ; the diminution in the number of undertakings ; the concentration of a number of undertakings into one hand, and it then becomes clear that it is the tendency of the capitalist mode of production to concentrate the means of production, which have become the monopoly of the capitalist class, into ever fewer hands. This development is ultimately tending towards a state of things where all the means of production of a nation, nay, even of the civilised world, are becoming the private property of a single company, which is able to dispose of it at its discretion; a state of things where the entire economic structure is welded into one gigantic concern, in which all have to serve one single master and everything belongs to one single owner. Private property in the means of production in capitalist society leads to a condition where all are propertyless with the exception of one single person. It leads, indeed, to its own abolition, to the dispossession of all, to the enslavement of all. But the development of capitalist commodity-production leads also to the abolition of its own basis. Capitalist exploitation becomes contradictory, if the exploiter can find no other purchasers of his commodities than those exploited by him. If the wage-workers are the only consumers, then the products embodying the sxirplus-value become unsaleable—valueless. Such a condition would be as terrible as it would be impossible. It can never come to that, because the mere approach to such a condition must so intensify the sufferings, antagonisms and contradictions in society that they become unbearable, that society collapses if the development has not previously been steered into a different channel. Bui if this condition will never be reached, we are rapidly drifting that way, indeed, more rapidly than most imagine. For while on the one hand the concentration of the separate capitalist concerns into fewer hands is proceeding, on the other hand with the development in the division of labour the mutual dependence of the seemingly independent undertakings is growing, as we have already seen. This mutual dependence, however, becomes more a one-sided dependence of the small capitalists upon the larger ones. Just as most of the seemingly independent workers carrying on home industries in reaity are only wage-workera of the capitalist, so there are already many capitalists having the appearance of independence, yet subservient to others, and many capitalist concerns that appear to be independent are in reality merely branches of one huge capitalist undertaking. And this dependence of the smaller capitalists upon the larger increases perhaps more rapidly than the concentration of the various concerns in the hands of the few. The economic fabrics of capitalist nations are already to-day, in the last resort, dominated and exploited by a few giant capitalists, and the concentration in the hands of a lew firms is little else than a mere change of form.

While the economic dependence of the great mass of the population upon the capitalist class is growing, within the capitalist class itself the dependence of the majority upon a minority (decreasing in number but ever increasing in power and wealth) becomes always greater. But this greater dependence brings no more security to the capitalists than to the proletarians, handicraftsmen, petty traders, and peasants. On the contrary, with them as with all the others, the insecurity of their position keeps pace with their growing dependence. Of course, the smaller capitalists suffer most in that respect, but the largest capital, nowadays, does not enjoy complete security.

We have already referred to a few causes of the growing insecurity of capitalist undertakings, for instance, that the sensitiveness of the entire fabric as far as it is affected by external disturbances, increases ; but as the capitalist method of production intensifies the antagonisms between the different classes and nations, and causes the masses facing each other to swell and their means of combat to become ever more formidable, it creates more opportunities for disturbance, which give rise to greater devastations. The growing productivity of labour not only increases the surplus-value usurped by the capitalist, but it also increases the amount of commodities which are placed on the market, and which the capitalist is compelled to dispose of. With the growing exploitation competition becomes more intensified, as does also the bitter struggle of investor against investor. And hand in hand with this development there proceeds a continual technical evolution ; new inventions and discoveries are unceasingly going forward, and in so doing destroy the value of existing things, thus making not only individual workers and single machines, but entire plants of machinery and even whole industries superfluous.

No capitalist can rely upon the future ; none knows with certainty whether he will be in a position to retain what he has acquired and leave it to his children.

. . ,

The capitalist class increasingly splits up into two sections: one section, growing in number, has become quite superfluous economically, and has nothing to do but squander and waste the increasing mass of usurped surplus-value that is not used as fresh capital. If one calls to mind what we have mentioned in the previous chapter regarding the position of the educated in present society, one will not be astonished to find that by far the greater number of the rich idlers are throwing their money away on mere coarse pleasures. The other section of the capitalists, those who have not yet become superfluous in their own undertakings, is decreasing in number, but their anxieties and responsibilities increase. While one section of the capitalists is decaying more and more owing to idle profligacy, the other section is perishing by never-ceasing competition. But the insecurity of existence of both sections grows. Thus the present method of production does not permit even the exploiters, even those who monopolise and usurp all the tremendous advantages, a complete enjoyment of them.

Considering the importance which crises have in the last few decades assumed in relation to our economic conditions, and in view of the want of understanding of the causes of crises on the part of a great many persons, we feel justified in entering further into the question.

The great modern crises, which now rule the world market, arise from over-production, and are the consequence of the anarchy necessarily connected with the production of commodities.

Over-production in the sense that more is produced than is required can take place under any system of production. But, of course, it can do no harm if the producers produce for their own use. If, for instance, a primitive peasant-family harvest more corn than they require, they store up the surplus for times of bad harvest, or in the case of their barns being full, they feed their cattle with it, or at the worst leave it on the field.

It is different in the case of the production of commodities. This production (in its developed form) presupposes that nobody produces for himself, but everybody for others. Everybody has to buy what he requires. But the entire production is by no means organised according to a plan; on the contrary, it is left to each producer to guess the extent of the demand for the goods he produces. On the other hand no one under commodity production (so soon as it has gone beyond the first stage of exchange) can purchase until he has sold. These are the two causes from which crises arise.

Let us for the purpose of amplification take tie simplest case. On one market there meet together a possessor of money—say a gold-digger with a pound’s worth of gold—a wine-grower with a little barrel of wine, a linen-weaver with a piece of linen, and a miller with a sack of flour. Let each of these commodities be of the value of one pound—a different supposition would make the case only more complicated without in any way affecting the result. Let those four commodity-owners he. the only ones on the market. Let us now suppose that each has calculated the requirements of the others correctly: the wine-grower sells his wine to the gold-digger, and buys with the pound which he receives for it, the piece of linen from the linen-weaver. Finally, the latter uses the proceeds of his linen for acquiring the sack of flour, and each one returns contented from the market.

In a year’s time the four again came together, each one expecting. to dispose of his commodity as before, and while the possessor of money does not dispise the wine of the wine-grower, the wine-grower, unfortunately, has no need for linen, or perhaps requires the money for the payment of a debt, and therefore prefers to go about in a torn shirt rather than purchase linen. The wine-grower keeps the pound in his pocket and goes home. The linen-weaver now waits in vain for a buyer, and the miller waits likewise. The family of the weaver may be hungry and covet the sack of flour, but the weaver has produced linen for which there was no demand, and as the linen was not required, there is no call for the flour. Weaver and miller have no money, and hence cannot buy what they want; and what they have produced is now “over-produced,” as is also what has been produced for them, for instance—in order to continue with the example—the table which the cabinet-maker expected would be purchased by the miller.

The most significant phenomena of an economic crisis are already given in the foregoing illustration. Of course, it does not take place under such simple conditions. At the beginning of commodity production each establishment still produces more or less for its own consumption: commodity production with each family forms merely part of its entire production. The linen-weaver and the miller we referred to for example possess each a piece of land and some cattle, and are both in a position to complacently wait until a buyer for their commodities puts in an appearance. If it comes to a pinch they can live without him. But in the beginning of commodity production the market is still small and easily surveyed, and production and consumption, and the entire social life, move, year in and year out, in the same rut. In the small communities of olden times one knew the other, his needs and his purchasing power, quite well. The economic fabric scarce changed the number of producers : the productivity of labour, the amount of products, the number of consumers, their needs, the sum of money at they; disposal, all changed but slowly, and each change was immediately discovered and taken into account.

But things take a different form with the advent of commerce. Under its influence production for self-consumption decreases continually, the individual producers of commodities, and still more the dealers in commodities, are getting ever more exclusively dependent upon the sale of their commodities, and particularly upon the quickest possible sale. Delay in or prevention of the sale of a commodity becomes ever more fatal to its owner, and may in certain circumstances lead to his economic ruin. At the same time the possibilities for depressions in commerce increase.

Through commerce the many different markets lying apart from each other are brought into communication; the entire market is thereby greatly extended, but also made less accessible to survey. And that development is furthered still more by the appearance of one or several intermediaries between producer and consumer, commerce making this necessary. At the same time it becomes easier to move commodities because of commerce and the development of the system of transit, and a small incentive suffices to concentrate them on one spot in large quantities.

An estimation of the demand for, and the existing supply of, commodities now becomes ever more uncertain. The development of statistics does not remove this uncertainty : it only makes it possible to estimate at all, which, from a certain stage of commodity production, would be impossible without statistics. The entire economic life becomes more and more dependent upon commercial speculation, which becomes ever more venturesome.

The merchant is a speculator from the start: speculation has not been invented on the Exchange. And speculating is a necessary function of the capitalist. By speculating, that is to say, by estimating the prospective demand; by buying his commodities where they are cheap (that is, where they are plentiful) and selling them where they are dear (that is, where they are scarce), the merchant helps to bring order into the chaos of the planless production of the private concerns which are independent of each other. But in his speculation he may also make mistakes, the more so as he has not much time for reflection, not being the only merchant in the world. Hundreds of thousands of competitors are waiting, like him, to make use of every favourable opportunity : whoever gets the first glimpse of it reaps the greatest advantage. That means one has to be quick, not to ponder long, not to make many enquiries, but to venture—nothing venture nothing have! But he may also lose. If on any market there is a great demand for a commodity, large quantities of it scon accumulate there, until there is more of it than the market can digest. Then the prices fall, the merchant has to sell cheap, and often with a loss, or to find another and better market for his goods. His losses at that game may be so great that they may ruin him.

Under the domination of developed commodity production on a market there are always either too many or too few commodities about. The bourgeois economists declare that to be a very wise and admirable ordinance, but we think differently : anyhow, it is inevitable,so long as commodity-production, from a certain stage onwards, exists. But this wise ordinance may in certain circumstances, and in the event of an exceptionally strong incentive, mean that the overloading of a market with commodities becomes so uncommonly great, that consequent losses of the merchants assume large proportions, and a great many of their number cannot meet their liabilities and become bankrupt. That means already a commercial crisis in its best form.

The development of the system of transit on the one hand, and of the system of credit on the other, facilitates the sudden flooding of a market with commodities, but in doing so it also furthers crises, and enhances their devastating effect Commercial crises had always to be limited in extent so long as petty enterprise was the prevalent form of production. It was not possible that under the influence of any incentive the amount of products produced for the entire market rapidly increased. Production under the domination of handicraft, like petty enterprise, is not capable of rapid extension. It cannot be enlarged by an increase in the number of workers, as at ordinary periods it already employs all the efficient members of the grade of population devoted to it. It can only be extended by adding to the labour-burden of the individual by prolonging the hours of labour, encroaching on Sunday rest, etc. But in the good old times the handicraftsman or peasant working on his own account, when he had not yet to contend with the competition of the large concern, showed no liking for such extension. Even if he consented to work overtime that was of little use, as the productivity of labour was not considerable.

That productivity changes with the advent of capitalist large concerns. As a means of enabling commerce to rapidly flood the market with commodities, it develops a hitherto unthought of capacity, not only extending the market to a world market, embracing the entire globe and increasing the number of intermediaries between producer and consumer, but also enabling production to follow every incentive of commerce and to expand by leaps and bounds.

Already the circumstance that the workers are now completely at the mercy of the capitalist; that he can increase their hours of labour, and interfere with their Sunday (and night) rest, enables the capitalist to extend production more quickly than was possible before. But one hour of surplus labour signifies to-day, with the great productivity of labour, quite a different extension of production to that at the time of handicraft. And the capitalists are also able to extend their concerns rapidly. Capital is a very elastic, pliable quantity, especially owing to the credit system. Flourishing conditions of business increase confidence, induce investments, shorten the period of circulation of a part of capital, and thus increase its scope and power. But the most important fact remains that there is always an industrial reserve army of workers at the disposal of capitalism. In that way the capitalist is in a position to extend his concern at any time, to engage new workmen, to increase production rapidly, and to make thoroughly good use of a favourable state of the market.

We have explained at the beginning of this chapter that under the domination of large industry, industrial capital comes always to the fore and increasingly dominates capitalist production. Within capitalist industry itself, however, special branches of industry become the leading ones, particularly the textile and iron industries. If one of them receives a special impetus, as for instance by the opening up of a new extensive market, like China, or by the sudden taking in hand of the, construction of a large railway line, for example in America, that particular branch of industry does not only expand, but it communicates the impetus thus received immediately to the entire economic structure of society. The capitalists extend their concerns, establish new ones, and thus increase the use of raw material and accessories ; new workers are engaged, while at the same time ground-rent, profits and wages rise. The demand for various commodities increases, while different industries begin to participate in the economic improvement, which ultimately becomes a general one. Then every undertaking seems bound to succeed, confidence is blindly bestowed and unlimited credit given ; anybody possessed of money endeavours to invest it profitably, and everyone participating in interest and profit, which are rapidly rising, seeks to transform some of it into capital. At such periods a general state of elation prevails.

In the meantime production has grown enormously, and the increased demand of the market has been satisfied; yet production continues. One capitalist knows nothing of the other, and even if the one or the other of them in sober moments has misgivings, these are stifled by the necessity of utilising the fluctuations of the market and of keeping pace with competition. The hindmost ia severely bitten. To dispose of the additionally produced commodities becomes an increasingly difficult and slower process ; the stock-rooms of the warehouses become full, but the ecstacy caused by the spell of prosperity continues. Then comes the time that one of the commercial houses is to pay for the goods which it had purchased months before from the manufacturer on credit. The goods are still unsold; it possesses the goods but not the money; it cannot fulfil its obligations; it goes bankrupt. But the manufacturer, too, has to discharge his financial responsibilities: as his debtors cannot pay, he too must fail. One bankruptcy succeeds another. A general panic ensues ; the previous blind confidence is superseded by distrust quite as blind ; the panic spreads in all directions, causing financial ruin everywhere.

The entire economic foundation of society is profoundly shaken. Every undertaking which is not firmly established collapses. Not only the’fraudulent undertakings are ruined, but also all those which at ordinary times have just managed to keep above water ; during periods of crisis the expropriation of peasants, handicraftsmen and small capitalists proceeds at a more rapid rate than at other times. But also many a large capitalist fails and no one is certain oi escaping ruin in the general collapse. And those among the large capitalists who happen to survive, participate liberally in the spoil; during periods of crisis net only the expropriation of ” small men,” but also the concentration of concerns into fewer hands and the extension of large fortunes proceeds more easily than at other times.

But no one knows whether he will survive the crisis; and while it lasts, and until such time as commerce has again to some extent assumed its ordinary aspect, all the terrors of the present method of production are prevailing to an extreme degree ; insecurity, want, prostitution and crime increase. Thousands starve or freeze to death, because they have produced too much food, clothing and shelter. Then it is demonstrated most vividly that the present productive forces are becoming less and less compatible with commodity production, and that the private ownership of the means of production becomes an ever greater curse, above all for the propertyless, but ultimately also for many of the propertied class.

Some economists expect that Combines will bring about the abolition of crises. Nothing is more erronous than such a view.

The regulation of production by the Combines presupposes, above all, that they embrace all the important branches of production and are built up op an international basis, t’hat is to say, that they extend over all the countries where the capitalist mode of production prevails. Until now there does not exist a single completely international Combine in any branch of industry, which could be taken as a criterion of the entire economic structure of society. International Combines are most difficult to establish and as difficult to maintain. Marx already remarked some fifty years ago, that not only, competition created monopoly, but monopoly created competition. The larger the profit derived by a number of firms from a Combine, the greater the danger of a powerful outside capitalist endeavouring to deprive them of these profits by establishing a competitive concern.

The Combines and. Trusts themselves become the object and cause of commercial speculations. They constitute the highest form of Joint Stock proprietorship, and .admittedly make it possible to carry swindling to its very extreme. While the era of swindling from 1871 to 1873 was an era of Joint Stock Companies, the latest era of swindling, viz., from 1899 to 1900, was an era of establishing Combines and Trusts, particularly in the tlnited States. Combines as a rule fail in preventing over-production. Their main object with regard to over-production does not consist of preventing it, but, of transferring its consequence from the capitalists to the workers and consumers. They exist for the purpose of assisting the large capitalists in living through crises by restricting production at certain times and discharging workmen, etc., without, however, interfering with profits. But let us suppose the improbable happens, namely, that within a certain period it would be possible to organise the large world-industries in Combines internationally and rigidly disciplined. What would be the consequence? Competition among the capitaliats in the same branch of industry would thereby, even in the most favourable case, be abolished only in one direction. It would here lead us too far to enquire into the consequences which must arise from the remaining sides of competition. But one point may here be considered, namely, the more the competition among the different owners of concerns in the same branch of industry disappears, the greater becomes the contest between them and the owners of concerns in those other branches of industry dependent upon their goods. While the struggle between the individual producers in the same industry ceases, the struggle between producers—the latter word taken in its widest sense—becomes more acute. In this sense each producer is consumer ; the cotton-spinner, for instance, apart from his personal consumption, is consumer of cotton, coals, machines, oil, etc. The whole capitalist class would then no longer be divided into single individuals, bnt into sections fighting one another most bitterly.

To-day each capitalist endeavours to produce as much as possible and to put on the market as many commodities as possible ; because the more commodities there are the more profit, under otherwise equal conditions. His production is limited only by the calculation of the possible absorption by the market, and, of course, by the extent of his capital. But in.the event of Combines becoming general we should not get regulated production and thereby a cessation of crises, as some illusionists tell us, but we might find that it would be the aim of each Combine to produce as little as possible, for the smaller the amount of-commodities the higher the prices. The old practice of merchants at periods of a glut in the market, of destroying a portion of the existing commodities, in order to obtain a profitable price for the remainder, would then become the general practice. It is clear that under such conditions society cannot exist. While each Combine aims at underproduction, it has on the other hand to force the other Combines, whose commodities it requires, into over-production. There are many ways of effecting that. The simplest one is to restrict its consumption more than,. the other Combine is restricting its own. Another way is to call science into play in order to create substitutes for the commodities w.hose production has been restricted. A third way is for the consumers concerned themselves to produce what they require.

Let us suppose that the copper mines form a Combine, restrict the production of copper, and force up its price—what would be the conse-,, quence ? Of the industrial capitalists in whose concerns copper is used in production, some would close their factories until more prosperous times, a few would, endeavour to use other metals in place of copper, while others again would themselves acquire or start copper mines, in order to become independent of the copper ring. In the end the Combine would burst—go bankrupt, that is to say there would be a crisis. Should that not be the case, the under production of the Combine would call forth an artificial restriction of production— that is to say, also a crisis—in those branches of industry which consume the products of the Combine as raw material or as tools, etc.

The Combines, therefore, do not get rid of crises. If they were to, succeed in that respect it could only be that the crises would assume a different form—but not a better one. Bankruptcies would not cease, the only difference being that they would become more extensive and not merely affect single capitalists, but entire sections of them. Combines cannot abolish crises, but are able to produce some of a far more disastrous character than anything we have hitherto witnessed.

Only when all Combines would be merged into one so all-embracing that the entire means of production of all the capitalist nations were contained therein, that is to say, only when private property in the means of production had been practically abolished would it be possible to do away with crises by means of Combines. On the other hand crises are inevitable from a certain point of economic development so long as private property in the means of production prevails. It is, therefore, not possible to proceed one-sidedly and to do away with only the harmful effects of private property while permitting the private property itself to continue.

We have seen that technical evolution proceeds uninterruptedly ; its scope extends continually, because from year to year new fields and branches of industry are conquered by large scale capitalist production; the productivity of labour, therefore, grows continually, that is to say, taking the totality of capitalist societies, it increases ever more rapidly. At the same time the accumulation of new capital takes place unceasingly. The more the exploitation of the single worker increases (not only in one country, but in all countries exploited by capitalists) the more grows also the sum total of surplus-value and the total amount of wealth which the capitalist class is able to put by in order to transform it into capital. Capitalist production, therefore, cannot remain limited to a certain stage of development ; its continual extension and that of its market is vital to its very existence: a standing still spells its end. While in times gone by the handicraft and small farming system produced results equal from year to year, and production, as a rule, increased only with the population, the capitalist method of production necessitates, as a matter of course, uninterrupted expansion of production, and every hindrance means a disease of society which becomes the more painful and unbearable the longer it lasts. Besides the temporary stimulous given to the expansion of production by temporary extensions of the market, we find that a permanent impulse is given by the conditions of production themselves; an impulse which, instead of having been caused by an extension of the market, on the contrary, makes a continual extension of it necessary.

The field for extending the market of capitalist production ia certainly tremendous; it transgresses all local and national limitations, claiming the entire globe for its market. But it has also caused the globe to shrink very considerably. Even a hundred years ago there were, apart from the western parts of Europe, only several maritime countries and islands that formed the market for the capitalist industry, which was principally carried on by England. So tremendous, however, were the efforts and the avarice of the capitalists and their helpers, and so gigantic the means at their disposal, that since then nearly all countries of the earth have been made accessible to the commodities of capitalist industry—which is no longer solely English—so that there remain scarcely any markets to be opened up, other than those from which nothing is to be gained—except fever and thrashings.

The astounding development of transport certainly makes possible a yearly increasing exploitation, yet with those people who are not quite savages, and have shown signs of culture or the desire for culture, the market presents an ever changing aspect. The penetration of commodities (of the products of large industry) kills the small national industry everywhere,—-not only in Europe,— and transforms the handicraftsmen and peasants into proletarians. Thereby important changes are caused in two directions in every market for capitalist industry. It diminishes the purchasing power of the population and thus works against the expansion of consumption on the markets concerned. But it produces there also—and that is even more important—by the creation of a proletariat, the basis for the introduction of the capitalist method of production. The European large industry is thus digging its own grave. From a certain point of development every further expansion of the market spells the creation of a new competitor. The large industry of the United States, which is not much older than, a generation, not only becomes independent of European industry, but is also making for the conquest of the whole of America ; even the more youthful Russian industry is beginning to alone supply with industrial commodities the tremendous territory which Russia commands in Europe and Asia. East India, China, Japan and Australia develope into industrial states, which sooner or later will become self-supporting in industrial respects ; in short the moment seems to be near, when the market for European industry not only becomes incapable of expansion, but begins to contract. But that would spell the bankruptcy of the entire capitalist society.

And already for some time expansion of the market proceeds much too slowly for the needs of capitalist production, which encounters always more and more hindrances, and finds it ever less possible to fully utilise its productive powers. The periods of economic booms become continually briefer, while the periods of crisis grow more extensive, particularly in old industrial countries, as for instance, England and France. Countries in which the capitalist method of production is comparatively new, as America and Germany, may yet have longer periods of prosperity. But there are always young capitalist countries with very brief boom periods and long periods of crisis, as Austria and Russia.

In consequence the quantity of the means of production insufficiently or not at all made use of, increases, as does the amount of wealth remaining uninvested and the number of labourers compelled to remain idle. In that number are not only included the crowds of unemployed, but also all those numerous (and ever more numerous) parasites on the body of society, who, prevented from industrial activity, seek to eke out a miserable existence by often superfluous, but nevertheless strenuous, occupations, such as small dealers, innkeepers, agents and representatives ; and to these must be added a very large number of slum proletarians divided into different sections, like the higher and lower showmen, criminals, the professional prostitutes with their bullies and other hangers-on—all existing in a similar way. These numbers further include the large crowd of persons in the personal service of the possessing class, and finally the many soldiers. The steady increase of armies during the last twenty years would scarcely have been possible without the over-production which enabled industry to dispense with the labour of so many workers.

Capitalist society is beginning to be suffocated by its own superfluity; it becomes ever less capable of bearing the full development of the productive forces which it has created, Always more productive forces have to lie fallow, always more products have to be wasted, if the system is not altogether to collapse.

The capitalist method of production, the substituting for petty enterprise capitalist production on a large scale (with the means of production as private property concentrated in lew hands and the producers as propertyless proletarians), this mode of production is the means of immensely increasing the productive power of labour, compared with the extremely limited productivity characteristic of handicraft and peasant agriculture. To accomplish this was the historic mission of the capitalist class. This class have fulfilled their task by bringing awful suffering upon the large mass of the people expropriated and exploited by them—but they have accomplished it. And this task was as much an historic necessity as were its two basic principles, namely, commodity production and private property in the means of production and products, so closely related to each other.

But while that task and its basic principles were historically necessary, they are no longer so to-day. The functions of the capitalist class are more and more relegated to paid officials, the large majority of the capitalists being reduced to the only function of consuming what others have.produced ; the capitalist has become as superfluous as was the feudal lord of a hundred years ago.

And even more. As were the feudal aristocracy in the eighteenth century, so are the capitalist class to-day already a hindrance to further development. Private property in the means of production has long ceased to guarantee to each producer the possession of his products and the liberty appertaining thereto. It is to-day rapidly making towards the abolition of this possession and of its liberty as far as the population of the capitalist nations is concerned ; and from having once been a basic social principle, it now becomes more and more the means of destroying the entire basis of society. And it has changed from being a means of rapidly stimulating the development of society’s productive forces into a means of increasingly compelling society to squander or keep fallow its productive forces.

Thus the character of private ownership in the means of production, not only as far as producers in petty enterprise, but also as far as the entire society is concerned, changes to its very opposite. Having once been the motive power of social development, it now becomes the cause of social deterioration and soefel bankruptcy.