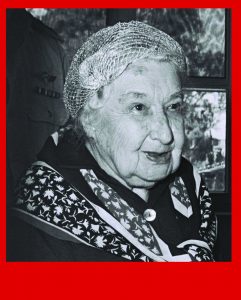

Angelica Balabanoff: To Bolshevism and back

Anželika Isaakovna Balabanova was born in Černigov, now Černihiv in Ukraine in August, probably around 1868. Her family was wealthy and she had a privileged upbringing. Yet, she soon realised that she did not fit in that type of high-class society and broke with her family, moving to Brussels to attend the Université Nouvelle. There she met leading figures in and around the Second International, such as Élisée Reclus, Émile Vandervelde, and Georgi Plekhanov.

Anželika Isaakovna Balabanova was born in Černigov, now Černihiv in Ukraine in August, probably around 1868. Her family was wealthy and she had a privileged upbringing. Yet, she soon realised that she did not fit in that type of high-class society and broke with her family, moving to Brussels to attend the Université Nouvelle. There she met leading figures in and around the Second International, such as Élisée Reclus, Émile Vandervelde, and Georgi Plekhanov.

In Leipzig, where she moved for a short while, she met Rosa Luxemburg who became her role model for the years to come. Then she moved to Berlin where she attended economics lectures and met various high-level SPD members such as Clara Zetkin and August Bebel. She heard about an Italian professor of philosophy, Antonio Labriola, who was quite well known amongst SPD students; so she decided to move to Rome where she attended Labriola’s lectures and met PSI founders Filippo Turati, Claudio Treves, and Turati’s partner, fellow Jewish Ukrainian, Anna Kuliscioff.

Mussolini

She became a member of the PSI in 1900. The Party asked her to move to Lausanne to educate the Italian immigrants to socialism. Here she met Benito Mussolini. She describes her first encounter with him in her book Traitor: Benito Mussolini and his ‘Conquest’ of power. He was destitute. He could not work because he was ‘ill’. ‘I’m good at nothing, not even to earn a piece of bread’, the future Duce told her. He was implicitly asking her help to translate a Kautsky pamphlet from German, in which he was a beginner, to earn some money. Out of pity he was invited here and there to give speeches at socialist conferences for a few francs. As we all know, he turned out to be an effective as well as a bombastic speaker.

In Switzerland she also founded Su Compagne (Come on Women Comrades) and she met the Menshevik leaders Martov and Axelrod. She joined in the League of Academic Marxists led by Chicherin, and she met Trotsky in Vienna in 1906. Balabanoff probably met Lenin for the first time in Berne. In 1907, she represented the Russian Academic Students at the 5th Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Party in London. The same year she also participated in her first meeting of the Second International in Stuttgart. Here she mainly contributed as a translator, and met Karl Liebknecht.

Together with Giacinto Serrati, future leader of the PSI, she helped Mussolini to leave Switzerland and find a good job in Trieste, a job that he was not able to keep for very long. She gave an interesting account of the day when Mussolini was elected as director of the local magazine Lotta di Classe (Class Struggle). The editor wanted to give up this position and offered it to Mussolini who he thought must be a good socialist considering his father’s politics (he had named his son after a Mexican revolutionary), and because he had no work commitments. The start of Mussolini‘s political fortune is often identified with the role he played at the 1912 Party Congress, when he proposed the motion to expel certain high-level reformists from the Party. Balabanoff tends to minimise his role. According to her, he was of course for their expulsion, but he was nominated to propose the motion to expel them only because he was pushed by the comrades of his region and because of the lack of other volunteers.

The victory of the intransigents in the leadership of the PSI pushed reformist Claudio Treves to resign from editing the party organ Avanti! Also in this case Mussolini was offered the job because of the lack of others without work and family commitments. When he was offered this post he was hesitant, and accepted only on condition that Balabanoff joined him. Balabanoff gives an account of Mussolini as being prone to corruption. She broke with him before his betrayal, because of his opportunistic and selfish behavior. Some believed that Balabanoff and Mussolini had a romantic relationship. This does not concern us, but what is sure is that Mussolini’s himself at the peak of his power admitted that without Balabanoff’s help he would have remained nobody.

Zimmerwald

At the outbreak of WWI in July 1914 she was called urgently to Brussels for a special meeting of the International. She proposed mass strikes against the war, while Viktor Adler and Jules Guesde were against the idea; she was backed only by the Labourists Keir Hardie and John Bruce Glasier. In August she met Plekhanov in Geneva who hoped to see the Italian party push for Italy’s intervention on the British-French-Russian side. In Italy, by now on the verge of intervention, it was hard to be a foreigner. When the German SPD member Albert Südekum visited Italy to push the PSI to convince the masses to intervene on the German-Austrian side, she was attacked as pro-German, although she reminded the crowd that she had been expelled by Austria in 1909 and by Germany earlier in 1914.

Balabanoff moved to Switzerland. In December 1914 she moved to Berne where she was instrumental in organising the conference of anti-war Social Democrats in Zimmerwald which took place in September 1915. She became a member of the executive bureau composed of the Swiss Social Democrat Grimm, the Italian Maximalist Lazzari and Rakovsky as secretary. The Zimmerwald manifesto, drafted by Trotsky, was the result of the clash of the moderates against Lenin’s Left fraction. The topics discussed at Zimmerwald were the peace action by the proletariat, the position with regards to the Second International, and the transformation of the war into a revolutionary civil war. The moderate view prevailed, thus Zimmerwald stood mainly for peace. It did not officially break with the Second International and did not propose to transform the war into a civil war

Bolshevik

Balabanoff lived in Zurich until the outbreak of the Russian revolution in February 1917. As did other revolutionaries, she left Switzerland to reach Russia on a special train, travelling with Martov, Axelrod and Lunacharsky. She became disillusioned with the February revolution and began to lean toward the Bolsheviks. In this period she saw Trotsky very often. She signed a resolution together with Trotsky, Kamenev and Riazanov for an outright boycott of the Russian Provisional Government.

She travelled to Stockholm to organise the 3rd conference of the Zimmerwald movement, which took place in September 1917. By now the moderate block was poorly represented and Lenin’s left prevailed. After the 1917 October revolution Lenin asked her to stay in Stockholm to propagate from there news about Russia, providing her with plenty of money to do this. On two occasions the Anti-Bolshevik League tried to assassinate her. In the end she tried to return to Moscow in September 1918, because Lenin had been severely injured by Fanny Kaplan’s attempted assassination. But because of the fighting between White and Red armies at the Finnish border she had to go back to Stockholm. She eventually managed to enter Russia in October. She met Lenin who was still recovering in his country house.

She was soon on the go again. In Zurich she was accused of carrying 100 million francs to finance the revolution in Italy. She was expelled from Switzerland, while Italy asked for her extradition to put her in jail there. She, together with other Bolsheviks, was transported to Germany where the November 1918 Revolution was taking place. However, with the victory of the SPD, they were sent to Russia. While in Berlin she was the guest of Adolph Joffe, the Bolshevik ambassador in Germany. She met some members of the Independent Social Democratic Party to convince them to follow the Bolsheviks, with no success.

When the new International, the Comintern, was established Lenin nominated Zinoviev as President and Balabanoff as secretary. Lenin needed her for her international networking. But she found herself doing mere administrative work for the Comintern. She was sent to Ukraine as commissioner of foreign affairs, but in 1920 the Bolsheviks had to flee Ukraine and she returned to Moscow. She had quite some friction with Zinoviev who tried to get rid of her in many ways.

In June of that year a delegation from the PSI arrived in Moscow led by Serrati, now its leader. The 2nd Congress of the Comintern was taking place at the same time, at which Lenin laid down the conditions for parties to join; for the Italians this would mean expelling open reformists like Turati. Serrati was against this and Balabanoff leant towards his position. When Lenin asked her to write something against Serrati she refused, telling him ‘I agree more with him than with you’.

Balabanoff reported another episode of Lenin’s despotism, at the 9th Congress of the Russian Communist Party in 1921. Alexandra Kollontai, a People’s Commissar, had criticised the Party for allowing very little autonomy to workers’ organisations; this was enough for Lenin to destroy her publicly. At the beginning of 1921 the peasants rose up against requisitions; many were executed. Kronstadt rose up against Bolshevik rule, leading to the bloody suppression of the local Soviet. These were the last straws that made her decide to leave Russia. Yet she needed Lenin’s permit to do so.

While Balabanoff was waiting to leave Russia Clara Zetkin arrived there. Zetkin stayed with her. According to Balabanoff’s account Zetkin seemed quite sensitive to and quite liked the Bolsheviks’ adulations. Zetkin tried to convince Balabanoff to remain in Russia. Balabanoff refused to be a translator at the 3rd Congress of the Comintern in June 1921. In December 1921 she was eventually allowed to leave Russia. From this point on she was an open anti-Bolshevik, though she was officially expelled from the RCP only in 1924.

Anti-Bolshevik

Lenin had asked her not to leave. She responded that she did not agree with the Bolsheviks’ despotic and demagogic methods. Years later when Trotsky was a refugee in Mexico she wrote to express her sympathy and she reminded him that the same methods of denigration used against him had been used by him against others. He answered: let’s not mention the past; those were different times; let’s not ruin our friendship.

Balabanoff had seen the Bolsheviks from close quarters and was convinced that without Lenin there would have been no Stalin. She explained that Lenin’s regime and the apparatus he had created allowed creatures like Stalin to develop, with no inhibitions, no brakes; in fact, the climate created by the regime fertilised this and encouraged the immoral tendency of the future dictator.

After leaving Russia, she stayed in Sweden and then she moved to Austria where Social Democrats like Otto Bauer were in power. Here she wrote for Arbeiter-Zeitung. In 1927 she moved to Paris, called there by the PSI in exile. She moved there, against her inclination, because the PSI lacked an old guard, Serrati having passed to the Communists shortly before his death; Lazzari had also died. At the Congress in January 1928 she was elected secretary of the Party and editor of Avanti! The party also decided to enter an anti-fascist coalition. She was against the United Front because of her anti-bolshevism and did not want to work with reformists or communists. Later, Trotsky wanted her to join his 4th International but she was not interested.

In November 1935 she obtained a visa to move to the US, where she got close to the rightwing Social Democrat, Gaetano Salvemini. In 1938 her autobiography My Life as a Rebel was published. In 1941 the Maximalist faction of the PSI ceased to exist and with it the legendary Avanti!

In 1947 she returned to Italy. Balabanoff was used by Saragat to promote his Workers’ Socialist Party of Italy (PSLI), a reformist party which was claiming at that time to continue the legacy of Turati’s 1892 PSI. She was in it because of her anti-bolshevism, but also because she believed that the PSLI was ideologically closer to the Italian reformists of the early 1900s. In 1955 she was invited to the Congress of the ‘Socialist International’ in Vienna where she was acclaimed as a living legend. She spent most of 1957 in Austria and Switzerland. She got close to Golda Meir and was pro-Israel. Finally, in 1960 she settled permanently in Rome. She died on 25 November 1965.

Balabanoff was the archetype of the revolutionary maximalist Social Democrat. Her Marxism was rather idealistic and lived as a faith. She saw herself as a missionary. Her mission was to convert workers to Marxism. With this in mind, one can understand why she took to heart Mussolini’s case, helping this idle anarcho-syndicalist to become a respected socialist, how she gave in to Lenin’s Bolshevism to pursue the maximal revolutionary goal, and how, at the same time, she defended the integrity of the Second International by means of Zimmerwald. Later in life, she stood for early 20th century Marxist reformism.

Balabanoff had the merit of exposing from first-hand experience Mussolini (Traitor), and above all Lenin and Bolshevism (Impressions of Lenin) in a period when it was not popular or even allowed. These two works are worth reading and why she is worth remembering.

CESCO