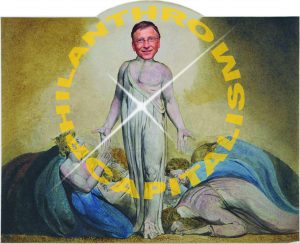

Philanthrocapitalism IV: The Messianic Rich

No such thing as a free gift

Part 3 here

The concluding article of our series on ‘philanthrocapitalism’

A significant motive driving philanthrocapitalism has to do with the tax incentives involved in charitable contributions. In most countries in the world, taxes constitute the primary source of government revenue (government borrowing, mainly through the bond market, is another important source). Paying less tax may be good for the businesses concerned but it obviously impacts on government revenue and, hence, the state’s capacity to finance reforms such as social welfare programmes. That in turn has consequences for private charity and the scale of the task it faces.

Some philanthrocapitalists appear to have grasped this point well enough. An example of this is the Boston-based project, Responsible Wealth – a ‘network of business leaders, investors, and inheritors in the richest 5%’ of the US population. It lists amongst its supporters Warren Buffet and Bill Gates Snr and is an offshoot of the aforementioned ‘United for a Fair Economy’ which it describes as ‘an organization that supports workers to organize and advocate for policies that make our economy more fair and equitable’ (www.responsiblewealth.org).

Amongst other things, it calls for higher taxes on the very rich and an increased level of public investment. However, the bizarre spectacle of billionaires taking up apparently left-wing causes might not be all that it seems. There is undoubtedly an element of self-interest involved, based on a recognition that the way things are panning out might not be good for the long-term stability and prosperity of capitalism itself. Though a system of cut-throat competition tends to foster ‘short-termism’, that does not rule out the possibility of sections of the capitalist ruling class rising above their circumstances to take a longer-term perspective.

Given that the state, famously described by Marx as the ‘executive committee of the ruling class’ has more leeway than capitalist corporations in what it is able to do within the context of market constraints, it is not surprising that such a longer-term perspective has tended to be associated with, and organised around, a more statist-oriented prescriptive approach. An example of this would be the kind of thinking that led to the setting up of the modern welfare state.

Germany under its distinctly non-left-wing chancellor, Bismarck, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was the first country to truly implement this idea of a welfare state. As Germany began to overtake Great Britain as an industrial power around this time, sections of the British capitalist class, alarmed by this development, began to take a serious interest in Germany’s state welfare programme. They began to see a connection between this and Germany’s growing industrial strength. Years later, in 1943, the millionaire Tory industrialist, Samuel Courtauld, articulated such thinking when he strongly endorsed the Beveridge Report’s proposal to set up a welfare state in Britain too on the grounds that ‘Social security of this nature will be about the most profitable long-term investment the country could make. It will not undermine the morale of the nations’ workers: it will ultimately lead to higher efficiency among them and a lowering of production costs’ (Manchester Guardian, 19 February 1943).

However, there is always that current of short-term thinking, generated by market competition, against which this longer-term perspective has to do constant battle. Economic boom conditions can, to some extent, shore up the latter perspective, by making state welfare programmes more affordable and, also, by empowering workers in their bid to increase the social wage. But when boom turns to bust as it did in the 1970s, ushering in an era of neoliberal austerity, philanthrocapitalism was then able to play a more prominent role, filling the vacuum created by the retreat of the welfare state. Philanthrocapitalism came to be increasingly identified as the bearer and nurturer of this longer-term perspective which the neoliberal state appeared to have abandoned in its bid to cut costs and restore national ‘competitiveness’. Hence the title of Bishop and Green’s book, Philanthrocapitalism: How the Rich can Save the World, referred to earlier. The thinking behind this was that enormous fortunes of the super-rich to some extent cushioned them from the short-term exigencies of cut-throat competition, giving them the freedom to spend their money on whatever they chose

The economics of philanthrocapitalism

Though philanthrocapitalists may profess to adopt a long-term perspective of wanting to ‘save the world’, their actions all too often belie the image they are intent upon projecting. Take the case of taxes. While some philanthrocapitalists such as those involved in ‘United for a Fair Economy’ seem intent upon advocating higher taxes for people like themselves, this does not apparently prevent them trying to run their own businesses in a manner deliberately designed to avoid paying taxes as far as possible, knowing full well the fiscal impact of this on a state’s budget and on the state’s ability to fund social welfare programmes.

This incongruity might seem puzzling but it is quite predictable in terms of game theory. Our ‘selfless’ philanthrocapitalists are quite willing to pay more taxes providing everyone else – meaning their market rivals – does as well. Until then, they will strenuously seek to avoid paying taxes as far as possible just like their ‘selfish’ counterparts in the capitalist class (who they will also try to emotionally blackmail through such stratagems as the ‘Giving Pledge’ to ensure the costs of philanthropy are shared more evenly). After all, taxation is ultimately a burden on the capitalist class, not the working class, and the squabble over that burden essentially boils down to a conflict of interests and perspectives between different groups of capitalists over how a capitalist economy ought to be administered.

Tax avoidance, unlike tax evasion, is of course perfectly legal under current legislation. The higher the taxes the stronger the incentive to avoid them, since taxation eats into profit margins and impairs the ability of businesses to compete on an increasingly globalised market. The significance of this to philanthrocapitalism lies in the fact that charitable donations are one of the ways in which the payment of taxes can be avoided.

In America, perhaps contrary to impressions, corporate taxes have been historically amongst the highest in the world (although Trump’s recent tax reform bill will cut these to a level just below the global average as well as reducing some personal taxes). Large US-based transnational corporations are particularly adept at tax avoidance, engaging in such sharp practices as transfer pricing and intra-corporate loans, and being able to employ expensive legal terms to ensure everything appears hunky dory and above board. Huge sums of money are offshored into tax havens or reinvested in other foreign operations. As Farok Contractor notes: ‘The accumulated, but unrepatriated, profits of American multinationals’ foreign subsidiaries—which have legally escaped US taxation—are estimated between $2.1 and $3 trillion’ (Rutgers Business Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 27–43).

As stated, making charitable donations is just another form of tax avoidance. Indeed, some of the most notable philanthrocapitalists are associated with businesses with a notorious record of tax avoidance. One example is Bill Gates. According to a report by The Independent: ‘Microsoft has reportedly avoided up to £100m a year in UK corporation tax by routing its sales through Ireland’ (19 June 2016). Over £8bn of revenues from computers and software bought by customers in the UK has been diverted to Ireland since 2011, under an arrangement agreed with HM Revenue & Customs.

Another example is Mark Zuckerberg. His corporation, Facebook, has been severely criticised for its tax avoidance stratagems and, like Microsoft, has resorted to funnelling profits through Ireland. In 2014, Facebook paid only a paltry £4,327 in corporation tax on an annual profit of £1.9bn (though the company has more recently agreed to pay several millions in taxes).

The case of Zuckerberg and Gates epitomises a trend in philanthrocapitalism. Instead of philanthrocapitalists giving directly to charities, they are increasingly setting up foundations of their own as a vehicle through which they can exercise ‘social entrepreneurship’, funnelling money to causes of their choosing. Some like Buffet seem to be the exception to this trend. In his case, his charitable donations have mainly gone to the Gates Foundation, the largest of its kind in the world, thereby amplifying its already enormous power and reach.

Indeed, the Gates Foundation is said to contribute about 10 percent of the total budget of the World Health Organisation which, critics claim, gives it undue influence on policy making. In a special report, the ‘Global Justice Now’ campaign group comment on the nefarious workings of the Foundation: ‘We argue that this is far from a neutral charitable strategy but instead an ideological commitment to promote neo-liberal economic policies and corporate globalisation. Big business is directly benefiting, in particular in the fields of agriculture and health, as a result of the foundation’s activities, despite evidence to show that business solutions are not the most effective’ (globaljustice.org.uk/resources/gated-development-gates-foundation-always-force-good).

How philanthrocapitalism goes about financing various causes, gives us more clues as to its real nature and intent.

While attention is focussed on the huge sums of money involved in charitable giving, it is easy to overlook what all that money is spent on. Quite a significant chunk of it is spent, in the first instance, on administrative costs and fundraising (which is, of course, indispensable in a capitalist money-based economy). According to a report by the Daily Mail (12 Dec 2015), one in five of the biggest charities in the UK are ‘spending less than half their income on good work’ and, in a few cases, as little as 1 percent.

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that many of these charities are little more than a lucrative gravy train for those employed in them. Indeed, the New York Times, (29 March, 2008) refers to a report on the fraudulent misuse of charitable money for personal gain in the United States. The authors of this report estimated that the overall costs of fraud came to a staggering $40 billion for 2006, or some 13 percent of the money given to charity in the US. In early 2007, another report by the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University (partnered by Google) provided some revealing data on the subject of what charitable money is spent on. According to the report, less than one third of the money that the American public gave to non-profit organisations in 2005 was focused on the needs of the economically disadvantaged. Of the total of $250 billion donated that year, less than $78 billion explicitly targeted those in need.

While we tend to think of charity as essentially an endeavour seeking to ease the plight of precisely those in need, this can be quite misleading. Ginia Bellafante in the New York Times (Sept 8, 2012) notes that:

‘Nationally, 32 percent of the $298 billion given away last year went to religious institutions, 13 percent to cultural organizations and 12 percent to social services, according to a report issued annually by the American Association of Fundraising Counsel. But if giving were conducted with the greatest consideration paid to the most urgent needs of the society, then Yale, a private institution with a $19.2 billion endowment, would arguably never receive another 50 cents.’

According to a Wikipedia entry on the billionaire Koch brothers: ‘Charles’ and David’s foundations have provided millions of dollars to a variety of organizations, including libertarian and conservative think tanks. Areas of funding include think tanks, political advocacy, climate change scepticism, higher education scholarships, cancer research, arts, and science’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koch_family_foundationswikipedia.org/wiki/Koch_family_foundations). That climate change deniers and the advocates of free markets should count as the recipients of philanthrocapitalist charity speaks volumes as to the supposed efficacy of such charity in addressing the needs of the poor. It is precisely the poor of the Global South, above all, who stand to lose most as a result of the very climate change which its deniers are unwittingly enabling.

However, it is arguably when charitable donations are funnelled into for-profit enterprises that the very term itself becomes most particularly questionable. As Matthew Reiz notes in his review of Linsey McGoey’s book, No Such Thing as a Free Gift: The Gates Foundation and the Price of Philanthropy (2015), there is a long-standing tradition of donating money to for–profit businesses in America and it has become more pronounced in recent years. McGoey’s book gives examples of this such as the Gates Foundation’s donations to Scholastic Inc, a large publisher of education material. Another recipient of the Foundation’s money was a project called M‑Pesa, for ‘which Vodafone and its subsidiaries built, in Kenya and then Tanzania, a system that allowed villagers access to mobile phone banking’ (www.timeshighereducation.com/features/the-perils-of-philanthrocapitalism).

As an article in The Economist put it, one of the things revolutionising American philanthropy is the ‘blurring of the distinction between the profit and the non-profit sectors. In health care, and even in education, for-profit companies are increasingly doing things that used to be reserved for non-profits. And non-profits increasingly model themselves on profit-making businesses. Business schools put on courses for voluntary workers. Non-profits hire managers from the private sector, and pay them accordingly. Some non-profits even charge for their services or spin-off profit-making subsidiaries’ (28 May1998).

Though the sums of money involved in charity donations are substantial – in America for example, by 2016, total giving to charitable organisations had risen to $390.05 billion, 72 percent of this coming from individuals compared with 15 percent by foundations and 5 percent by corporations and the rest by bequests – it is still small by comparison with state expenditures on welfare programmes. In America, if you include both federal and local government spending, the latter comes to about $1 trillion per year. Given that only a fraction of charitable giving in the US (which itself represents only 2.1 percent of GDP) is actually targeted on the needy this further underscores the utter absurdity of such brash claims about the super-rich wanting to ‘save the world’.

Philanthrocapitalism is not about saving the world. It is about saving capitalism through a face-saving attempt to justify what cannot be justified. It is about promoting the patronising belief that the poor depend upon the super-rich when the reality is the complete opposite.

ROBIN COX